Charlie Chaplin, born in London, 1889, was touring the USA

with Fred Karno's London Comedians when he was signed by Adam

and Charles Kessel of Keystone at $150 a week and started at Mack

Sennett's studio in Edendale, CA, in December 1913. In a year,

he made 35 single and half-reelers and the six-reel "Tillie's

Punctured Romance." Mabel Normand, Chester Conklin, Mack

Swain, Charles Murray, Charles Parrott (Charley Chase), Edgar

Kennedy and Slim Summerville appeared in this, as well as many

of the shorts, which included "Between  Showers"

(by Henry Lehrman with Ford Sterling), "The Rounders"

(by Chaplin with Fatty Arbuckle, Al St. John), and "His Musical

Career."

Showers"

(by Henry Lehrman with Ford Sterling), "The Rounders"

(by Chaplin with Fatty Arbuckle, Al St. John), and "His Musical

Career."

Chaplin joined Essanay at $1,250 a week. He wrote, directed and acted in 15 films, mostly two-reelers, including "The Bank." Edna Purviance was, in most cases, the leading lady. Rollie Totheroh was cameraman and continued as consultant until Chaplin left Hollywood.

In the middle of 1916, Chaplin signed with Mutual for 12 comedies at a salary of $10,000 per week plus $150,000 bonus. These were all two-reelers and include "One A.M." (with Charlie alone except for a brief appearance by Albert Austin as a cab driver), "The Pawnshop," and "The Adventurer." Undoubtedly, the most famous was "Easy Street." The same supporting players appear throughout, often in odd guises.

Contemporary features include "Intolerance" by D.W. Griffith, Mary Pickford in "The Poor Little Rich Girl," Douglas Fairbanks in "The Americano," Theda Bara in "The Darling of Paris," and Owen Nares and Fay Compton in "One Summer's Day." As for the other comedians, Buster Keaton (smiling) was supporting Arbuckle in Paramount Comedies, Harold Lloyd had just put on his glasses, and Lloyd Hamilton, Bobby Vernon, and Charlie Murray & Co. were going strong. Stan Laurel did not start until 1917.

The story of "Easy Street" is sublime, typically Chaplin, and a provocative comment on its unusually apposite title. For, of course, "Easy Street" is anything but easy for its raw guardian. A tramp wanders into a mission service and immediately falls in love with the Pastor's daughter. He, therefore, joins the police and ingeniously captures a hooligan. His casual theft of food for the hooligan's wife is mistaken for open-handed generosity by the Pastor's daughter, and together they visit another poor family. Meanwhile, the hooligan escapes, and a terrific chase and fight ensues, ending triumphantly for the tramp. And next Sunday, a reformed Easy Street attends the Mission in force . . .

This simple and wholly admirable narrative, with its pungent

cause-and-effect, its development leading logically up a rising

curve to a strong climax, and its excellent final sequence, makes

an ideal basis for Chaplin's liberal gift of comedy. The deft

continuity, witty and detailed characterizations, and ever-riotous

incident make the full version a  rare

gem. The abridged 9.5mm version, which will discussed here on

account of its greater availability, loses little in its skillfully

pruned state, though, of course, tempo is upset, and some details

of Chaplin's careful pattern are lost. The additional titles inserted

to bridge the gaps of pruned footage conceal the title-free perfection

of Chaplin's original script.

rare

gem. The abridged 9.5mm version, which will discussed here on

account of its greater availability, loses little in its skillfully

pruned state, though, of course, tempo is upset, and some details

of Chaplin's careful pattern are lost. The additional titles inserted

to bridge the gaps of pruned footage conceal the title-free perfection

of Chaplin's original script.

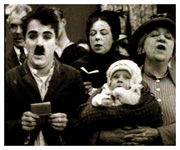

The opening discovers Chaplin asleep outside the Hope Mission. The Pastor's daughter, heavily back-lit in a medium close-up with terrific depth of focus, leads the singing. It is her voice that rouses the tramp. He wanders in. As he passes the collection box, his palms itch - a neatly detailed bit of pantomime. He cannot read, so he holds his hymnbook for an infant in arms next to him.

Intercuts are medium close-ups of the Pastor and his daughter, the latter drenched with back-top lighting. In a curiously intense close-up, Chaplin looks back at the girl with an expression of devotion. This serious moment is well placed and admirably played. He sits there dumbly while the rest file out, then, conscience-stricken (and with inimitable comic counterpoint), he hands back the collection box which he had secreted in the front of his baggy trousers.

Long and mid-shots of a hectic fight introduce Easy Street. A cut-in long shot of a knocked-out policeman arriving on stretcher at the police station affords an admirably pithy comment on the tough residents. Outside the police station, a notice announces a vacancy (cause and effect), and Charlie meanders into the picture.

Whether the ludicrously redundant title, "Policeman wanted at once," was inserted to cover the small continuity gap, cater for people refusing to read the large notice, or to spin out the length of the reel in the days of notched titles is open to free debate. Charlie valiantly enters the police station.

Back at Easy Street, the chief

hooligan shakes the money from the borrowed trousers of another

disposed-of policeman, and a detailed close-up shows the money

landing in the road and hands greedily grabbing. Then in a well-arranged

long-shot, they all rush after their victim whose helmet is left

forlornly picked out by incongruous sunshine in the foreground.

Back at Easy Street, the chief

hooligan shakes the money from the borrowed trousers of another

disposed-of policeman, and a detailed close-up shows the money

landing in the road and hands greedily grabbing. Then in a well-arranged

long-shot, they all rush after their victim whose helmet is left

forlornly picked out by incongruous sunshine in the foreground.

The tough work in Easy Street is crosscut with Charlie's comic enrolment, the latter culminating in the pungent instruction - "Your beat's on Easy Street."

With the hooligan towering in the foreground and the camera looking straight along one sidewalk, a really thoughtful long-shot introduces Charlie as a diminutive speck, which, with those characteristic steps and mien that made him the most famous comedian in the world, comes bravely up to its enormous opponent. Several interpolated titles ruin the flow but cannot spoil the pantomime of the action that follows - Charlie's nonchalant foot-wiping on his fallen colleague's coat, his idle walk towards the telephone, his pretense that the receiver is first a musical then an optical instrument, and then his mighty swipe with his truncheon at the hooligan's head - and utter panic when this produces no more effect than to make him scratch his ear.

Then comes a famous and memorable incident. The hooligan leisurely bends double a gas street lamp to demonstrate his might, and Charlie nips on to his shoulders and turns on the gas. A horrific close-up emphasizes the gassing. Charlie walks straight over the unconscious hulk and phones for help. In medium close-up, the sergeant receives the call. In long shot the cops turn out, and they bear away their prize, idly watched by the captor.

In mid-shot of a street vendor's stall with the vendor sleeping

peacefully near the camera, the hooligan's wife does her furtive

"shopping." Charlie accosts her, but she dissolves in

tears - and he does the same - then hastily pinches another good

load from the sleeping vendor. As he hands over the spoil, the

Pastor's daughter comes up and compliments  him

prettily. All this action is covered with the same mid-shot camera

position. But intercut with suspense-laden counterpoint are shots

of the handcuffed hooligan at the police station. Now he breaks

completely loose, and, hurling one limp body before him, he strides

out.

him

prettily. All this action is covered with the same mid-shot camera

position. But intercut with suspense-laden counterpoint are shots

of the handcuffed hooligan at the police station. Now he breaks

completely loose, and, hurling one limp body before him, he strides

out.

In a room simply seething with children of graduated ages, Charlie distributes chicken-feed and pins his star badge on the diminutive father, an absolutely typical Chaplin vulgarity of pure and mellow vintage.

Across the street, the hooligan is already fighting his wife in their bedroom. In mid-shot he hurls the washbasin at her. In long-shot (looking down the street from a high angle), it sails across the top of the frame but will be missed by many in the audience owing to the confusion of other irrelevant movement in the shot. And in mid-shot, it cops the father, who collapses in Charlie's arms.

Here, two or three frames have been lost at the cut, the basin already being smashed when the mid-shot begins. Charlie accents irregularities, and a nice high-angle long shot covers his entry into the house opposite. Meanwhile the hooligan hurls more crockery, again hits the father, and again two or three frames missing at the cut spoil what should be a very crisp effect.

Charlie has thumped his chest and

started up the stairs, blissfully unaware of danger. And a brief

long-shot in the bedroom shows him appear in the doorway, realize

the horrible truth, and dart away. And down the stairs, in and

out of houses, and back up again, the hooligan chases in an abandon

of meticulously perfect timing.

Charlie has thumped his chest and

started up the stairs, blissfully unaware of danger. And a brief

long-shot in the bedroom shows him appear in the doorway, realize

the horrible truth, and dart away. And down the stairs, in and

out of houses, and back up again, the hooligan chases in an abandon

of meticulously perfect timing.

Another horrific close-up shows the hooligan swallow the key of the locked bedroom door. So Charlie nimbly escapes through the window sliding down the drainpipe. Then, carelessly he re-enters the house, meets the hooligan on the stairs, escapes again and tips a cast iron stove on him from the first floor window, successfully knocking him out. Charlie sits down for a quiet smoke, but the chair has no back.

The Easy Street roughs have by now collected, and, as the Pastor's daughter approaches the house, she is grabbed and carried down to an unsavoury basement. Emerging from the house, Charlie also is grabbed and borne away in a long shot which was almost identically repeated in "The Great Dictator."

Then, a typically excellent sequence:

a. L.S. (in basement) A frightful bounder lurches towards the

girl

b. M.S. (in street) The roughs drop Charlie through a coal hole

. . .

c. L.S. (as a) . . . he lands in the basements, gets well coshed

by the bounder, collapses onto a bench . . .

d. M.S. . . . sits up wryly, pulls out the spike he had sat on

and, aroused . . .

e. L.S. (similar to a) . . . bashes the bounder who's embracing

the girl, deals swiping blows at him, whose momentum swings h im around to clasp the girl. Another rough

enters and gets kicked down

im around to clasp the girl. Another rough

enters and gets kicked down

f. L.S. (adjacent basement) Charlie kicks down a whole mob, and

. . .

g. M.S. (same, further back) . . . they all collapse

h. L.S. (as f) They advance, he knocks one out, swings another

over his shoulder, trips a third over his back. . .

. . . and finally conquers the leader who attacks from the rear,

and jumps off from him back through the coal hole. He fervently

approaches the girl but spoils the effect by tripping over the

hole again! Then tries again and succeeds. . .

The whole inimitable last sequence of the film is covered in a title and only two shots, a glaring failure to apply film technique. But such is the joyous and delightful effect that recriminations are futile. The title is pure, scintillating inspiration: "Love backed by Force; Forgiveness Sweet; Bring Hope and Peace to 'Easy Street'." The first shot shows from high angle Easy Street next Sunday. The new Mission catches the eye, and all paths lead to it.

In the second and last shot, policeman Charlie occupies the foreground and greets the reformed toughs as they pass with their wives arrayed in their Sunday best. The hooligan's wife starts at the street side of he sidewalk, so he courteously changes places with her. Charlie watches them, then brightens as the Girl approaches him. Carefully they link arms, but she has somehow got to the outside of the pavement. . . so Charlie carefully changes over, and the camera pans a little to follow them as they enter the New Mission.

Such is the stuff of this famous comedy. And now that it

has endured for 25 years (including 12 years of talkies), and

since in spite of mutilation and imperfect prints, it never fails

to captivate its audiences, we can well believe that it will endure

forever.