"An Italian Straw Hat" is a comedy of manners, a superlatively witty and brilliant satire on the petty conventionalism of the French bourgeoisie of the 1890's. It positively overflows with what are known as "typical Lubitsch touches." Each one of the players has a definite characteristic, as will be noted from the revised British print credits -- and there is also the sublime inspiration of making the bride (properly the central figure) a mere cog, whereas the expectedly obscure deaf uncle is continually caught up into prominence and ultimately provides the solution to what must be the most hectically complex triviality ever conceived.

René Clair, one-time journalist on L'Intransigeant, passed through phases of acting until 1923 when he directed his first film, "The Crazy Ray" ("Paris qui dort"). This and its successor, "Entr'acte," were witty, had an undercurrent of social commentary, and were full of trick photography. Three others preceded "An Italian Straw Hat," about which William Hunter in "Scrutiny of Cinema" aptly writes:

"Clair has achieved a remarkable success by a delicacy of wit and an admirable use of a medium over which he has a mature control. 'Le Chapeau de Paille d'Italie' is certainly among the half dozen or so films that really count."

After one more silent film, "Les Deux Timides"

(again much trick photography), René Clair won fame with

"Sous les Toits de Paris" (Albert Prejean), "Le

Million" (Annabella), the superb "A  Nous

la Liberté" (1931), and later, "The Ghost Goes

West" (for Alexander Korda at Denham with Robert Donat in

1935). This last might have been by any competent director, only

traces of Clair wit being noticeable. He then went to Hollywood

and now has several American productions to his credit. Some of

these lack the Clair wit -- e.g., "Ten Little Indians"

(1945) -- but some contain very pleasant ideas and touches lightly

strewn amongst them, notably "I Married a Witch" (with

Fredric March and Veronica Lake, 1943) and "It Happened Tomorrow"

(1944).

Nous

la Liberté" (1931), and later, "The Ghost Goes

West" (for Alexander Korda at Denham with Robert Donat in

1935). This last might have been by any competent director, only

traces of Clair wit being noticeable. He then went to Hollywood

and now has several American productions to his credit. Some of

these lack the Clair wit -- e.g., "Ten Little Indians"

(1945) -- but some contain very pleasant ideas and touches lightly

strewn amongst them, notably "I Married a Witch" (with

Fredric March and Veronica Lake, 1943) and "It Happened Tomorrow"

(1944).

The plea for intelligence, for rising above petty worries like lost gloves, for refusing to be constrained by petty convention, make "An Italian Straw Hat" a crusader in human propaganda. The sublimely naturalistic sets, the superb uniformity of the acting, and the flawless action continuity are the measure of René Clair's technical proficiency. The photography is purely objective, lighting is "all-over," focus is hard throughout in the American style. As will be illustrated in the analysis which follows, Clair is the master of straight narrative development with unobtrusive technical skill, ingeniously interpreting narrative by means of characters and action that afford witty commentaries on pomp, convention and officialdom -- which makes his work such a powerful satire.

The trade paper, The Cinema of 9/1/30, summarized the film thus:

"Delightful social irony and hilarious situations welded into divertingly sustained comedy. Amusing characterizations which are ironic criticisms. Witty situations and deft development. Quite dependable light entertainment for high class halls."The film opens briskly with the introduction of the bride's aunt and uncle who have just arrived. Then we see the bride and, carrying his new shoes, the bride's father. They beg him to hurry. His cousin and another arrival assist him with his shoes. The abbreviated version makes it hard to pick up the foibles given to each character, as listed in the cast above, but the traditional greeting becomes uproariously funny through sheer repetition.

Meanwhile, in sparkling tracking shots, the bridegroom (Albert Prejean) drives in the Bois de Vincennes till his whip catches in a tree. While he runs back to recover it, his horse finds, and starts eating, a straw hat. He is dismayed, and more so at the indignant cry of a soldier who appears just in the wood -- and the agonized cry of a lady (Olga Tschechowa) who appears a moment later. Apologetically handing back the hat, he hurries off, twirling his whip again, until he recalls the danger. The others hail a providential carriage and give chase.

Impeccable Acting

As is the case throughout, the acting is impeccable, and the photography

objectively brilliant, the crowning point of interest lying in

the subtle wit of the director. This is a film from which one

obtains entertainment (above the normal, obvious narrative entertainment)

in proportion to the amount of thought one applies. Thus, in the

mid-shot of the horse cheerfully eating the hat, one can read

the animal's thought: "If women persist in wearing perfectly

good food on their heads, they must expect occasional misunderstandings."

The bridegroom arrives at his new home, is let in by his

valet, and meets deaf Uncle Vesinet - two more well-defined types.

His pursuers drive up as his carriage is led away, and they enter

his house (shutting out a small but enthusiastic crowd who sense

drama - another tasty aside). Then, very neatly arranged . . .

C.S. Photograph of a girl (the bride)

C.S. Bridegroom smiles pleasingly at it, then frowns, looks up

and around, frowns still more at . . .

M.S. Madame (wearing wrecked hat), then soldier, who enter room.

L.S. The carriages drive up (one assisted by barking dog)

M.S. Soldier expostulates, but is shown at window (first floor)

. . .

L.S. (looking down from window)

a perfect orgy of kissing as massed relations meet

L.S. (looking down from window)

a perfect orgy of kissing as massed relations meet

M.S. - and Ferdinand nonchalantly indicates that he's the bridegroom

- a scathingly sarcastic revelation of the obvious.

. . . and then the intruders have to be swept into the bedroom beyond for concealment as the father (tight shoes) enters, followed by the bride (charmingly unruffled) and her cousin (still feeling for his lost glove).

Ferdinand approaches his bride but is swept back by the father - a magnificent gesture, implicitly stating, "Time for all that later." He then looks at his watch and raises his eyes to heaven. In the next room, Madame faints. Ferdinand gets rid of the others. Uncle Vesinet has heard and seen nothing. Ferdinand thoughtfully plugs his ear-trumpet and resumes arguments with the soldier who explains that Madame cannot return to her husband without a whole hat.

Then follows an uproarious sequence with the soldier's increasing

violence, Madame's continual fainting, the valet's entrances and

horror, and Uncle Vesinet, sublimely unaware of any irregularity.

The latter is shown in several shots, very appropriately cut-in

as repetition laugh-raisers, dozing serenely amid the turmoil.

Then he walks out and is besieged by vain questions from the relations.

The father stalks in and drags

out Ferdinand while the two are concealed behind the doors.

The father stalks in and drags

out Ferdinand while the two are concealed behind the doors.

At the Town Hall, Ferdinand espies a milliner's shop before entering. So, when the Mayor does not immediately arrive, he sprints out to it.

Then . . .

L.S. The Mayor enters the hall. All stand. He sits down. All sit

down.

M.S. Ferdinand's chair, occupied by hat and gloves only (action

of sitting down continued in background).

C.S. the Mayor looks at the empty chair

M.S. The Father speaks to him with an anguished gesture . . .

then dashes to the milliner's and grabs Ferdinand who just manages

to get the address of the customer who had the last leghorn hat

stocked . . . The narrative content of the four shots above quoted

is remarkable, only equaled in directorial inspiration by their

comedy content.

Ripe Guying

The civic ceremony culminates in the moving, enjoyed, and trite

homily delivered with a wealth of gesture by the Mayor. These

facets are ripely guyed by Clair's direction, the more subtle

guying being backed up by a heartily played gag as the uncle's

tie comes adrift and everyone misinterprets the aunt's frenzied

gestures. His yell as she finally pinches his arm can almost be

heard. Then the impatient Ferdinand breaks into applause at what

might have been, but obviously was not, the end of the Mayor's

speech. He leads the way out, so all must follow - except Uncle

Vesinet who  claps tardily and,

when accused of ill manners, courteously accepts the imagined

congratulations.

claps tardily and,

when accused of ill manners, courteously accepts the imagined

congratulations.

The reception proceeds with singing and dancing and Ferdinand extremely worried, until his valet enters and looks so lugubriously gloomy that he imagines, in a model-shot flashback, the total wreck of his new home. So he dashes off to the address obtained from the milliner.

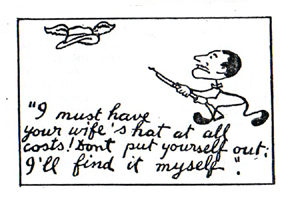

His entrance here is nicely portrayed. In close-up, his head pokes around the door. He sees, mid-shot, a screen. Over it hang trousers, and from it protrude two bare feet, wriggling. Then to the audience is given a view round the screen of M. Beauperthuis (Jim Gerald) taking his footbath. Ferdinand demands the hat, the dialogue title concerned being that one reproduced herewith (at left). These titles, accompanied by apt cartoons, were apparently reproduced specially for the 9.5mm version by the Pathé Paris office, since the English 35mm version of the film had conventional printed titles.

The Identity of the Lady

The relations have followed Ferdinand. The Father, clutching his

plant and walking slightly unsteadily (for the party was good),

enters and sees the feet behind the screen (now being briskly

dried) and also sees the pair of shoes, which he deliberately

puts on with a sigh of relief and totters out. The enraged M.

Beauperthuis mutteringly crams on the wrong 'uns, and dashes upstairs

to corner Ferdinand with two pistols in the bedroom. But Ferdinand

tells the whole story in lengthy titles since, unfortunately,

the recounting sequence, done in pantomime against stage backdrops

(a witty idea), has been cut. It dawns (heavily over-emphasized

in close-ups of the woman, the soldier and the hat) on Monsieur

that his lady may be involved, and the fact is brought

home forcefully when Ferdinand knocks over a photograph which,

to his horror, shows whose wife is in his house. Then M. Beauperthuis

sprints off to the house, and Ferdinand sprints after him.

Night falls as the relations reach the house and are refused admittance by the valet "while the lady is there." This proves too much for the father who declares the marriage off and goes to collect the presents. Ferdinand protests, but Uncle Vesinet opens his - to reveal a leghorn hat. In ecstasy Ferdinand snatches up the box and dashes into the house while the gendarmes round up the relations and take them to the police station as suspicious characters!

Inside his house, Ferdinand opens the box. It is empty. Uncle Vesinet still had the hat . . . but M. Beauperthuis bursts in, and the two escape to the street. The soldier "knows one of the gendarmes" and recovers the hat. However, it falls on a lamp, and Ferdinand screens M. Beauperthuis with an umbrella claiming rain, while it is recovered and Madame is sped away. . .

The released relations are intrigued at the bride's account of her husband's gallantry. M. Beauperthuis returns to find his wife in bed and is left with a single doubt and a pair of tight shoes - and the young couple return to normal.

Clever Montage

René Clair's selection and composition of material is so

good that much of the montage ingenuity must be attributed to

him, though a technician is named as editor (This is the English

editor who hacked out 1,340 ft. of the best scenes. They survive

in the original version). For instance, the entry of M. Beauperthuis

at Ferdinand's house is neat. One long shot of the stairs shows

the latter start down, turn hurriedly back, and then M. Beauperthuis

appears. This holding of a shot for supplementary actions is now

associated with Lubitsch and his shots of doors, but actually

dates from the 1914 Keystone comedy period and was used by Chaplin,

for example, in "Easy Street" (Mutual: 1917).

Further examples of Clair's feeling for the narrative image - that is, pictorial counterpoint used to describe action are the scenario passages quoted, as well as such sublime moments as when the Mayor stands with his most telling gesture nipped in the bud. . . and when the feet are seen behind the screen -- these cases all depend for their unusual power on the intercutting of shots with conflicting contents.

There is also a considerable comic use of inanimate objects. Thus, double doors flung open act as screens. Furniture hurries out of his house under its own volition in Ferdinand's distraught imagination. The wife, inanimate in a dead faint, falls into his unwilling arms and balks his argument with the soldier. These are in the Buster Keaton tradition, as is the imperturbability of the valet who enters with gloomy disapprobation at the most awkward moments.

Clair, as the scenario writer, must be commended chiefly for his generous loading of every sequence with details and gags. Thus, in addition to the plain action content of the Father's chase to the milliner's shop, we have the glimpse of the assistant in Ferdinand's arms as the door opens and also the aside of the Father treading heavily on the other lady's new hat. Here (though none of the critics dared say it) Clair has learned from Harold Lloyd, whose silent films were constructed from the cream of a super-abundance of gags and situations contrived by his staff.

Clair surpasses Lloyd and his team, however, in turning to account such typically human touches as the delighted assistance of the collected carriage drivers in directing the Father after the errant groom has entered the milliner's shop. The nearest comparable Lloyd gag the present writer can recall is that in "Safety Last!" (1923) when Lloyd, on the third story of his climb up the skyscraper, is ruthlessly urged on by a group of pretty girls leaning from a window.

The acting is so uniformly excellent that one can hardly credit the players being other than types. Some will be remembered in delightfully obscure small parts in Clair's French talkies. Olga Tschechowa came to England for "Moulin Rouge" (1928 by E.A. Dupont) and in 1930 was in UFA's "Drei von der Tankstelle," shown in England as "Chemin du Paradis" (with Lillian Harvey). Jim Gerald is recalled with a hearty laugh in Anthony Asquith's 1939 "French Without Tears."

The objective photography (which incidentally does full justice to the minutely detailed sets of Lazare Meerson) is typical of the French school with which one associates "Carmen," "Königsmark," "The Chess Player," etc. The films of the Russian émigrés (e.g. "Michael Strogoff") being rather more subjective in approach, partly perhaps due to their more complete divorce from the stage. René Clair, though a master of all phases of film technique, is undoubtedly least interested in the photography. This can clearly be seen in his later films, which are typically American in photographic treatment, whereas Fritz Lang always manages to infuse photographic individuality. To be more specific, Clair permits crudities such as straight-on instead of low-angle shots of toppling masonry, and pretty-pretty studio ground mists in "Ten Little Indians" while Lang gives us the bold diagonals, the inimitable dark street scenes in "Scarlet Street."

"An Italian Straw Hat" is a film on which one can think back with many a casual chuckle, so steeped is it with sly but wholesome and constructively useful wit. For after all, the damaged hat could be explained. The wedding day was a success in spite of the trouble. There was an identical hat lying in Ferdinand's room all the time. And the only person left in doubt at the end was the only one who had been aggressively suspicious. On the thoughtful interlacing of such relevant wit with its properly cinematic action-interpretation does the constructional perfection of this excellent film depend.

(Thanks to Lenny Borger, who presented the film with such success at Pordenone in 2007, for his help with this piece. - KB)