"For sheer pictorial beauty of structural architecture,

'Siegfried' has never been equaled for no company could afford

to spend money as did Decla-Dioskop in 1922-23 . . . 'Siegfried'

was far from being pure film, far from the naturalism of the Soviets

or the individualism of Pabst, but it was restrained, simplified

pageantry, rendered with a minimum of decoration to gain the maximum

of massed effect. Who can forget the tall, dark forests; the birch

glade, bespattered with flowers where Siegfried was slain; the

procession of Günther's court,

seen distantly through the mail-clad legs of the sentinels; the

calm, silent atmosphere of the castle rooms, with their simple

heraldic decoration;  and above all, the

dream of the hawks . . ."

and above all, the

dream of the hawks . . ."

This summary by Paul Rotha in "The Film Till Now" accurately conveys the greatness and implies the weakness of a film which will remain a landmark in the history of large-scale screen spectacle, and for which Fritz Lang did in fact create in the studio a complete replica of the peoples and palaces of the Nibelungen Saga.

The realism is profound, but it is the sets and the masses that fill the screen. So crowded out are the human emotions that the characters never come to life - just as they remain in legendary remoteness in the book ("The Nibelunglied" by Vilmar). This is accentuated in the available version, where most of the pruning has been at the expense of the more intimate shots. But nonetheless, Fritz Lang's typical disinterestedness in the human angle is marked.

"Siegfried" had its premiere at the Albert Hall, and was released contemporarily with several famous films: spectacles ("The Covered Wagon," "The Hunchback of Notre Dame," "Sodom and Gomorrah" by Michael Courtice (better known as Curtiz), an Austrian film), comedy (Harold Lloyd's "Girl Shy," Buster Keaton's "Sherlock Jr.") and drama (Pola Negri in "The Spanish Dancer" and Gloria Swanson in "Zaza"), not to mention Douglas Fairbanks Jr.'s first film "Stephen Steps Out."

The American film had at this time already established its

domination, though the German company, subsidized, had unlimited

capital to spend in competition. The Americans were, however,

cinematic, whereas strong theatrical elements marred the German

product until late 1924. Moreover, the somber tones and intellectuality

found disfavour compared with  the American

cult of slick brilliance.

the American

cult of slick brilliance.

The following list of sequences in the available version

will show how the narrative has been constructed. The rather episodic

tendency is largely due to the condensation.

1. Siegfried forges a sword and hears of Kriemhild.

2. A glimpse of Worms castle and Kriemhild.

3. Siegfried leaves the armourer's cave.

4. Siegfried meets and kills the dragon, bathes in its blood.

5. A minstrel at Worms castle informs Günther

and his court of the above.

6. Siegfried meets and overpowers Alberich, King of the Nibelungs.

7. Alberich shows Siegfried the Nibelungen treasure, but dies

for treachery.

8. Siegfried arrives at Worms, asks for Kriemhild's hand, agrees

to help Günther in his aim to

make Brunhild his wife.

9. Brunhild introduced in her castle surrounded by a lake of flames.

10. Siegfried and Günther approach

and enter, meet Brunhild.

11. Brunhild matches her prowess against Günther,

but he is assisted by Siegfried, and she is defeated.

12. Triumphal return to Worms.

13. Double marriage in cathedral.

14. Siegfried subdues Brunhild on the bridal night, removing her

bracelet.

15. Kriemhild finds this bracelet.

16. Siegfried explains to her its source.

17. Brunhild belittles Kriemhild who in anger produces the bracelet.

Brunhild saved from suicide, demands Siegfried's death.

18. Hagen enquires as to Siegfried's one place of vulnerability.

19. Brunhild continually demands of Günther

that Siegfried be killed.

20. Kriemhild embroiders a cross to indicate Siegfried's vulnerability.

21. Hagen practices with a sword.

22. A hunt is called in the forest.

23. Kriemhild, troubled by a dream, begs Siegfried not to go.

24. In the forest, Hagen challenges Siegfried to a race to the

spring but runs instead to a high crag whence he kills Siegfried.

25. Brunhild hysterically taunts Günther

with murdering his friend. Kriemhild awakes, finds Siegfried's

body, and swears vengeance on Hagen.

26. Siegfried lies in state, and Brunhild has taken her own life.

The film opens with the studio-built exterior of Mime's

cavern. Then, within are introduced Siegfried with god-like appearance

and Mime, his mentor. The arrangement is properly cinematic, appropriate

action carrying the narrative through the introductions. The perfection

of Siegfried's skills is well shown by the action of the sword

severing a falling feather. The cavern interior is lovely  in detail (such as the fire and the quenching

trough and the leather bellows, pumped with Langish gesture and

the two weak shafts of "sunlight").

in detail (such as the fire and the quenching

trough and the leather bellows, pumped with Langish gesture and

the two weak shafts of "sunlight").

Old Mime gives a trace of sorrow to his admiration of Siegfried's skill, and excellent touch but unusual for Lang. George John makes Mime a memorable figure, a fine achievement in so minute a part. Outside, a gnome speaks of Kriemhild. Siegfried listens, holding his fine white horse. We see a backlit long shot of Worms, a bold conception of light and shade. One shot of Kriemhild taken from behind a line of guards throws back at the audience the whole vastness of the castle pageantry. Shots in the cathedral, including a close-up of Kriemhild, complete the sequence. The gnomes deride Siegfried's decision to win Kriemhild, and Mime points grimly into the distance suggesting the perilous quest.

The dragon is introduced by an iris-in, the point of the iris being at the lower right hand corner of the screen so that the head only of the dragon is seen at first. This useful device, the ex-centric iris, is now considered obsolete, an anomaly in a period when cavorting cameras with obtrusive personalities are in vogue. The next shot is one of the finest studio creations ever - the huge forest, one vast composition of verticals with sunlight making a fascinating diagonal splash, through which Siegfried and his white horse picturesquely wend.(1)

The dragon was a full-size studio property manufactured from steel and rubber, weighing one and a half tons, and 70 feet in length, controlled by 32 men. From the first Langish long shot of Siegfried, sword raised, leaping down towards the dragon, the fight is a slick assembly of well-chosen shots, including a gruesome 16-frame close-up of the blinded eye. The sequence fades out on a boldly composed medium close-up of Siegfried's back, linden leaf on shoulder, under the dark blood of the dragon.

After introductory title, Günther is shown in a finely posed mid-shot which shouts his characteristic weakness and indecision. Mid-shot followed by a close-up introduces Hagen, his missing right eye exemplifying brutal villainy. Then a low-angle shot shows the Minstrel, singing of Siegfried's progress. These three were famous character actors. Günther is Theodor Loos of "Metropolis," and the Minstrel is Bernhard Goetzke who had leads in Lang's 1921 "Destiny" and Carmine Gallone's 1926 Italian spectacle "Last Days of Pompeii" with Maria Corda and Victor Varconi.

"Led by Birds, he has entered the Nibelungen Kingdom

to win a wondrous treasure." So concludes the minstrel, and

white mist rolls away across the screen to reveal another set of sinister beauty - the dark valley

with rising mist and gaunt tree and the lurking figure of Alberich.

This latter is lit too crisply to match correctly. When Alberich

unfolds his net, he vanishes. This is too sudden, and the explanatory

title too laboured. Better is the fading away of the person behind

the net, as done later in the film.

set of sinister beauty - the dark valley

with rising mist and gaunt tree and the lurking figure of Alberich.

This latter is lit too crisply to match correctly. When Alberich

unfolds his net, he vanishes. This is too sudden, and the explanatory

title too laboured. Better is the fading away of the person behind

the net, as done later in the film.

Siegfried cleverly acts the fight with the invisible dwarf, but the reappearance also is not 100 percent correct, the high angle shot of the last throw being held two frames too long before Alberich appears. General slickness, however, glosses over these errors at first viewing. Alberich begs forgiveness in a pleading high angle close-up recalling the same player at the machine in "Metropolis."(2) Finally, the Langish gesture, he leads Siegfried from the valley in a full long shot - the mist has swirled higher.

Down a deep rocky chasm, and into a dark cavern wherein the moonlight weakly struggles, Siegfried follows Alberich. They pass into another cavern filled with strange shapes and still water. Alberich lights the way with a luminous sphere. A ring of dwarfs bear a huge plate of jewels. Alberich conjures a vision of his workers forging a vast crown. Then, among the jewels is shown Balmung, the famous sword. While Siegfried's attention is diverted, Alberich attempts to kill him, but . . .

a. L.S. Siegfried turns, raises his sword.

b. M.S. (detail) Siegfried's legs strain.

c. C.S. One of the dwarfs, uneasy . . .

d. M.S. (as b) Alberich's crown falls to the ground - Alberich

falls.

e. CM.S. Siegfried stands back.

f. L.S. The same - dark background - Alberich at his feet.

g. CM.S. Alberich - his luminous sphere flashes under his hand;

he says . . .

h. TITLE "People of the Nibelungen, return to stone."

i. CM.S. (as g) His hand covers his heart.

j. L.S. (as f) Siegfried looks down at him.

k. M.S. The dwarfs supporting the plate; they turn to stone.

l. L.S. Siegfried stands back in wonderment.

m. CM.S. Alberich has turned to stone.

n. L.S. (as l) Siegfried holds aloft the sword.

Slow iris out - the iris closing at the top of the frame on the

handle of Balmung.

This excellent arrangement of shots

concludes a fine sequence with a dramatic intensity seldom bettered

by Fritz Lang - completely losing the hampering chains of theatrical

presentation, his best cinematic instincts came to the fore with

outstanding results. The restrained beauty of the cavern sets

is also admirable. There is an interesting Langish link with "Metropolis"

- the sphere in shot (g) is comparable with the lights on the

machine Freder works in the Machine Room.

This excellent arrangement of shots

concludes a fine sequence with a dramatic intensity seldom bettered

by Fritz Lang - completely losing the hampering chains of theatrical

presentation, his best cinematic instincts came to the fore with

outstanding results. The restrained beauty of the cavern sets

is also admirable. There is an interesting Langish link with "Metropolis"

- the sphere in shot (g) is comparable with the lights on the

machine Freder works in the Machine Room.

A low-angle shot shows Siegfried with his escort of vassal Kings on the drawbridge of Worms. Hagen dissuades, but Günther welcomes "the son of Siegmund." Then the massive doors are opened (their mammoth solidity is really impressive) and they enter. Siegfried slowly approaches Günther - impressively, in high-angle long shot. He asks Kriemhild's hand. Hagen interposes the suggestion of aid in Günther's journey to Brunhild, but Siegfried violently opposes the vassal implication. A struggle is only averted by Kriemhild's appearance.

The above is of special note in that extraordinary symmetry is maintained in the camera set-ups. Kriemhild approaches. The loving cup ritual is nicely handled but has been upset in the abbreviated version available. Finally, Siegfried and Günther join hands in an oath of loyalty, and, symbolically, as the shot fades out, the black hand of Hagen grips them both. This last shot has been given a soot-and-whitewash treatment or dramatic emphasis, a successful if rather crude method.

Brunhild is introduced in close-up with quick iris-in and out, very appropriately. In long shot we see her castle, surrounded by fire. Over the rocky plain Siegfried and Günther approach with their company. The flame dies down. They are admitted. Ingeniously, Brunhild is shown as assuming that it is Siegfried who has come to conquer her. Excellently, opposed back and front shots jerk the tempo of her approach. Then, turning to Günther, she indicates the tattered shield of her previous opponent. Siegfried fingers his invisible net. Outside the castle gates he raises the net and disappears - effectively this time by fading away.

Crowds take their places in the natural arena. Then comes a shot of unusually well calculated camera-angle. Brunhild stands at the top of a flight of steps, her height filling the frame, the camera being at the level of her feet. Small in the distance but approaching and thus gradually coming to equal her in height, comes Günther.

The triple contest is straightforwardly presented, but the

beams of light in the sky are interesting. Siegfried neatly superimposed

as a light outline, assists Günther

who  prevails. The impact of the javelin

on Brunhild's shield is well shown in two short flashes of eleven

frames each. In the last shot she collapses, unfortunately weakening

the effect by over-acting.

prevails. The impact of the javelin

on Brunhild's shield is well shown in two short flashes of eleven

frames each. In the last shot she collapses, unfortunately weakening

the effect by over-acting.

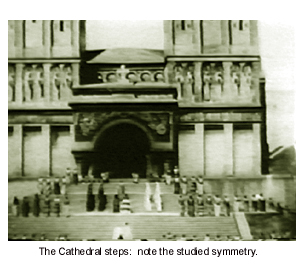

A spacious long shot shows the return to Worms. After Brunhild's anger at Siegfried's betrothal to Kriemhild has been soothed, all proceed up the vast steps to the cathedral, a beautiful set done a grave injustice in the available version by appearing on the screen for only 80 frames - 5 seconds - during which appreciation for its imposing grandeur is impossible. This shot again is absolutely symmetrical, an arrangement here ideally suitable.

This symmetry is maintained throughout the long and mid-shots of the double wedding in the cathedral, including the close-up of ringing bells. The sequence appropriately ends with a perfectly central iris-out.

The subduing of Brunhild by Siegfried, in close and mid-shots intercut with mid-shots of the uneasily waiting Günther, is aptly photographed with harsh accent lights, giving a contrasty image and heavy shadows. The device of Siegfried taking on Günther's appearance is well presented from a cynical point of view in well-matched mixed long shots, but is dramatically confusing as the unexplained power is rather incredible. The change back is in a complex shot, since Günther is in the picture throughout Siegfried's re-assumption of his own appearance. This involved a masked shot one part of which contains a mix. The timing is excellent. Siegfried thoughtfully holds the bracelet he wrested from Brunhild - emphasised in an unnecessary close-up.

In close shots of sparkling brilliance, arranged so that the frame is fringed with blossom, Siegfried sits in a bower whistling to the birds. Kriemhild approaches and, seeing him thus engaged, raises her eyes to heaven with, unfortunately, a ludicrous effect. Siegfried takes her in his arms with an appropriate, sweeping gesture. Dully, in calculated contrast, Brunhild watches from a window. Her jealous despair is well portrayed in the one mid-shot. Kriemhild shows the bracelet she has just found to Siegfried, but . . .

a. C.S. his smile fades to a frown . . .

b. C.S. the bracelet on her arm - his hand grips her arm. . .

c. M.S. He says to her . . .

d. TITLE "Take off that bracelet. She who possesses the treasure

of he Nibelungen has no need of this accursed jewelry" .

. .

e. M.S. he says and turns away (continuation of c).

The choice and arrangement of shots (a) and (b) and (c)

are excellent, and their dramatic impact remarkable. In contrast,

the sequence concludes lamely with Siegfried's explanation about

the bracelet, all covered in the camera set-up (c) varied only

by medium close-up and by long shot for the fade-out. And once

again perfect symmetry is  observed,

this time with irritating pointlessness.

observed,

this time with irritating pointlessness.

On the cathedral steps, Brunhild insults Kriemhild and pushes past her. This is rendered in a rather confusing series of shots intercut with questionable effect - confusing in that, having been filmed from opposite sides against sky background, the players seem to jerk around, i.e., the geography is inadequately established. One low-angle shot of the two women is excellently composed and most impressive. Langishly, after Kriemhild has blurted out the truth, Brunhild strides down to Günther. He hangs his head (another unfortunately over-emphasised gesture). Brunhild dashes to the drawbridge and is saved from suicide by Hagen. "Kill Siegfried," she cries, and again, to Günther (the title being printed in larger type), "KILL SIEGFRIED."

Sequence 18 is over-titled and interesting only for its excellent first shot, a delayed iris-in of Hagen. The delayed iris throws sinister suspense into this appearance.

Sequence 19 is tersely arranged in harshly lit shots of remarkable power - implacable Brunhild, distraught Günther, evilly murderous Hagen in a dramatic composition of verticals as he intrudes through a curtain. Then, in a fine close-up with hard light on her face and Günther in dull shadow, Brunhild whispers to him, "The craven who stole my bracelet, robbed me also of my honour." - and edges behind him. He turns, then follows another dull close-up of him against a perfectly white background, a dramatic effect. He announces a hunt . . .

Then, concisely,

M.S. Kriemhild embroiders . . .

C.S. . . . a cross (circular mask) MIX TO

L.S. In armoury, Hagen practices with a javelin.

FADE OUT

In the centre of a long shot teeming with movement a huntsman blows his horn. In the castle, Siegfried makes to start but Kriemhild tries to dissuade him from going. Intercut are low-angle shots of the huntsman. At last, Siegfried tears himself away. Kriemhild, at the embrasure waves, and, by a blossom-laden bower, he waves back. Finally, in long-shot looking down the length of he drawbridge, the hunt sets out. Within, Queen Ute comforts Kriemhild.

This fine sequence approached perfection in the original.

Abbreviation has spoiled the slow rhythm of shots expressing Kriemhild's

grim foreboding, and, most grievously,  the

dream of the hawks has gone. This remarkable cartoon perfectly

conveyed the dread of Kriemhild's dream - a daring, successful,

and curiously un-Langish experiment.

the

dream of the hawks has gone. This remarkable cartoon perfectly

conveyed the dread of Kriemhild's dream - a daring, successful,

and curiously un-Langish experiment.

The hunt concludes. Günther sits aside with his thoughts. Hagen holds the selected javelin, and at Siegfried's request, mentions the spring. Then this is shown in long-shot looking down the birch glade - another lovely studio design. Siegfried races ahead and throws himself down to drink at the spring. Hagen, above, darkly silhouetted against a evening sky, throws the javelin, and it pierces Siegfried's shoulder.

Protracted death scenes are always dependent primarily upon the actor for their effect. In the present case, full credit must go to Paul Richter. First in long shot in the flower-decked glade he staggers to his feet again, and his terrible cry, twice uttered, of "Hagen" (no title) comes eerily from the screen. In another long shot he staggers back towards Hagen. And, at last, confronting his murderer, he desperately raises his shield, before finally collapsing. This is a flawless performance.

The sequence concludes with a stark, contrasty long shot of the scene, with accusing arms pointing at Hagen. Correctly, with dramatic counterpoint, the reaction at the Castle is portrayed by carefully chosen shots, their arrangement a model of implied narrative.

a. L.S. Kriemhild's bedroom - the curtains blow - she sits

up in bed.

b. M.S. (exterior) A dog howls.

c. C.S. (dark interior) Brunhild - she realises, closes her eyes.

d. L.S. (as a) She looks towards the billowing curtains.

e. L.S. (exterior) Wind blows along he castle drawbridge.

f. L.S. (as a)

g. L.S. (as e) With guttering torches, Hagen leading Siegfried's

body is borne along to the castle. His white horse follows . .

.

Then Günther informs Brunhild to be greeted with hysterical laughter. In hopelessly over-long and theatrical long shot, Kriemhild walks across a room to Siegfried's body and touches his wound. Cut-in is a piece of perfect symbolism - the shot of him waving goodbye to her by the bower mixes to a shot of the bower without flowers, all withered, and so disposed as to resemble a skeleton skull, a weird and eerie effect.

And then, grim reminder of the traditional belief that the victim's wound bleeds again in the presence of his murderer. A C.S. shows a trickle of blood and, in foreboding L.S., there stands Hagen . . .

The remainder of the film is interesting

only for the design and composition of the theatrical shots of

Kriemhild's threat to Hagen, where from low camera angle a finely

massive ceiling is seen - and the final lying-in-state in the

cathedral. The last shot has an eccentric iris-out on Kriemhild,

a curiously unsatisfactory effect as Siegfried's body is the centre

of dramatic interest. The idea was presumably to focus attention

on to Kriemhild in view of the film's sequel. This sequel, inevitably

doomed to failure by its defeatist theme, is a vast, spectacular

pageant of boredom, available on four S reels as "Kriemhild's

Revenge." Professional English release was in December 1925

under the title "The She-Devil" (7,000 feet).

The remainder of the film is interesting

only for the design and composition of the theatrical shots of

Kriemhild's threat to Hagen, where from low camera angle a finely

massive ceiling is seen - and the final lying-in-state in the

cathedral. The last shot has an eccentric iris-out on Kriemhild,

a curiously unsatisfactory effect as Siegfried's body is the centre

of dramatic interest. The idea was presumably to focus attention

on to Kriemhild in view of the film's sequel. This sequel, inevitably

doomed to failure by its defeatist theme, is a vast, spectacular

pageant of boredom, available on four S reels as "Kriemhild's

Revenge." Professional English release was in December 1925

under the title "The She-Devil" (7,000 feet).

"Siegfried" is one of the rare films which one can see and see again and cherish as a lovely, legendary memory. The beauty of the design is absolutely beyond reproach. The photography, though too objective, harmonises with the design scheme particularly as regards perspective and symmetry - and Fritz Lang's direction and balanced grouping (e.g. on cathedral steps, see still) are conceived in similar strain.

Had it not been for the theatrical tendency, so marked at the end and so painfully similar in grandiose misfiring to the end of "Metropolis," "Siegfried" would indeed have been a masterpiece. Not till "The Spy" (1928) did Lang finally realize the weakness and cinematic error of the static long shot. This admirable thriller was a gem of cinematic action-drama, shot counterpoint, being on a rare scale of sustained and unobtrusive brilliance, far surpassing "Metropolis" in this respect.

It is an extremely happy thing that in "Man Hunt" (1941 with Walter Pidgeon, Joan Bennett - 20th Century Fox production) Fritz Lang made another superlative thriller, with distinct Langishness. The film reassuringly proved his remembrance of his old power, nor had he forgotten the camera. The street and Underground scenes are perfect. "Man Hunt" and "Citizen Kane" alone make 1941 cinematically worthwhile.

Apart from Lang and his wife (who wrote the scenario), the players and the architects merit a share of the praises. Most of the former have been noted above, but Gertrude Arnold as Queen Ute appears in only a few shots in the available version, and Frieda Richard as the Reader of the Runes has altogether disappeared. This player was in "Cinderella" and "Faust."

The superb architecture sings for itself. Only one big creation is wholly missing, namely Siegfried's "Dragon Ship." From this exact replica of the ancient Norse galleys, Brunhild walked majestically ashore over the shields of 50 knights. The available version, however, is much to be thankful for. Through less than half the original it preserves the spirit and presents the lasting beauty of this picturesque legend.

(1) Alfred Hitchcock, working in Germany as an art director on Graham Cutt's "The Blackguard" (1925), had to pull down the forest to accommodate a vast staircase.

(2) "Siegfried" was, of course, released in 1923

and "Metropolis" in 1926.