Of the sixty scientific and adventure novels by Jules Verne

between 1863 and 1907, Michael Strogoff, the sixteenth,

was written in 1876 and appeared as a play in 1880. The novel

runs to 120,000 words and is a virile piece crammed with action

and with a struggle theme of the highest order. In addition, it

is full of detail drawn in by the author with his usual impeccable

accuracy. It is alive with strong characters. The background is

itself famous; the period dramatic and historic. Inevitably, therefore,

the whole is a more majestic drama than (for example) The Lost

World (First National, 1925).

It is fortunate that a French company made this film. The spectacle

is vast without being vulgarly colossal, the players wear their

costumes as though they belong to them, and the extras and the

sets carry a unique stamp of realism. The adaptation of the long

book is interesting in its extraordinary faithfulness.

Only a third of the original is preserved in the version available,

which causes a painfully episodic quality to intrude and, by creating

gaps which remove motives, renders some  actions

and situations inexplicable. The brief treatment of what remains

is as follows:

actions

and situations inexplicable. The brief treatment of what remains

is as follows:

At a ball in Moscow two reporters glean the news that the

Tartars are rising, led by the traitor Ogareff, and intend to

attack Irkutsk. The Czar summons his Courier, Michael Strogoff,

to deliver a message stating the date his army will relieve that

town.

On the Volga, Strogoff meets Nadia Fedor, traveling the same way.

Also on the boat is Ogareff, disguised, and his accomplice, Sangarre.

Strogoff hears that they know of the departure of the Courier.

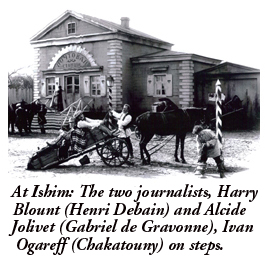

At Ishim, a man demands and obtains the horse team booked by Strogoff

who dares not jeopardise his mission by dueling.

Ferrying the river Irtych, Strogoff and Nadia are attacked by

Tartars. Nadia is captured, and Strogoff, wounded, drifts to the

river bank. A mujik rescues him.

At Omsk the Tartars prepare their attack. Strogoff is recognised

by his mother and has to deny he is her son. They are observed,

and she is arrested and taken before Ogareff while he escapes

by horse.

Strogoff reaches a telegraph office at Kolyvan where Blount and

Jolivet are sending off despatches. The Tartars attack, and he

is captured and his horse killed.

Marfa Strogoff and Nadia meet as prisoners, and Ogareff commands

that Marfa be flogged till she points out her son, the Courier.

But Strogoff saves her, strikes Ogareff whom he recognises as

the man at Ishim, and is taken before the Emir Feofar Khan for

judgment. His message having been seized, he is blinded by the

blade of a red-hot sabre passed before his eyes.

Nadia and Strogoff toil on towards Irkutsk while Ogareff is accepted

as the Courier on delivering the message at the Governor's Palace.

Beneath the ramparts of Irkutsk, the Tartars await the signal

to attack, arranged by the traitor in the Palace. Naptha from

the burst reservoirs is floated down the river and fired. In the

confusion, Nadia and Strogoff enter the Palace and, meeting Ogareff

face to face in fair fight, Strogoff kills him after explaining

how the tears in his eyes upon beholding his mother's face for

the last time saved his sight. Ogareff's scheme of betrayal from

within is thus foiled, and the Russians gain a notable victory

and save their city.

In Moscow, Strogoff is suitably decorated by the Czar, and, with

full ceremony in Irkutsk Cathedral, he and Nadia are married,

the Press being represented at this function by Blount and Jolivet.

This narrative, whose content of

action verbs as against speech and thoughts will create a favourable

impression at once, differs from "textbook" construction

(i.e. rising pitch of interest up to a defined dramatic climax,

as in The Lighthouse by the Sea) in that the dramatic pitch

is established and maintained throughout - the slight modulations

of romantic passages and comedy relief merely serving to emphasise

the sustained strong drama. Verne used the fact of Strogoff not

being blind after all as his climax, just as in Around the

World in 80 Days he used the fact of Phineas Fogg being in

time after all. However, in Film an explanation cannot be a climax,

and wisely we are shown finally the beautifully happy ceremony

of marriage in the Cathedral, which only occupies a paragraph

in the book, the fight with Ogareff coming within six pages of

the end.

This narrative, whose content of

action verbs as against speech and thoughts will create a favourable

impression at once, differs from "textbook" construction

(i.e. rising pitch of interest up to a defined dramatic climax,

as in The Lighthouse by the Sea) in that the dramatic pitch

is established and maintained throughout - the slight modulations

of romantic passages and comedy relief merely serving to emphasise

the sustained strong drama. Verne used the fact of Strogoff not

being blind after all as his climax, just as in Around the

World in 80 Days he used the fact of Phineas Fogg being in

time after all. However, in Film an explanation cannot be a climax,

and wisely we are shown finally the beautifully happy ceremony

of marriage in the Cathedral, which only occupies a paragraph

in the book, the fight with Ogareff coming within six pages of

the end.

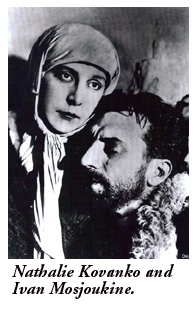

The famous names connected with the film are Mosjoukine, the Star,

and Tourjanski, the Director, and, to a minor degree, Nathalie

Kovanko, who played many silent leads and starred in a talkie,

Tourjanksi's Volga in Flames. Ivan Mosjoukine, a

Russian born in 1889, played leads in numerous Russian films up

to the Civil War when, in company with Tourjanski, Alexandre Volkov,

and Dmitri Buchowetski, he went to France. His French films, of

which the most famous apart from Michael Strogoff are Kean

by Volkov, and The Late Matthew Pascal by Marcel l'Herbier

(though by different directors) were obviously largely controlled

in the direction and acting by Mosjoukine himself, who had also

directed in his earlier days. One only has to compare these films

to note the star's favourite gestures and groupings. Much the

same applied, of course, to the American stars, but in fairness

to Mosjoukine, it must be said that he avoided scene-stealing

(with the resultant dramatic unbalance often noticed in American

Stellar Vehicles) and that his acting was always very good and

often excellent. Adventure drama, preferably with a role calling

for varying make-up, always attracted him. Thus, in Michael

Strogoff, he has three guises. He proceeded to America in

1926, appeared in one film (Surrender (1927)) then returned

to Europe via Berlin where he made The President to fulfill

his contract with Universal - a strangely un-American film, strong,

Mosjoukineish, and having a leading part calling for contrasting

characterisations. In 1929 he played opposite Lil Dagover in his

last silent film, The White Devil, directed by Volkov for

UFA. Tourjanksi made several spectacular films in France, and

is remembered particularly for the German-produced Volga, Volga

(1928-9, with Lilian Hall-Davis and Hans von Schlettow).

Both of these men are associated with essentially virile films,

creating strong characters and setting them in dramatic situations.

They were also extremely competent and experienced in film technique,

Mosjoukine in particular having dabbled successfully in highbrow

films of which he himself had written the scenarios. Hence we

expect to find in Michael Strogoff passages of brilliance

comparable with the finest in Vaudeville and Pitz Palu.

The film is further notable in its almost complete avoidance of

the semi-static pageantry which was a feature of French large-scale

silent films and was caused by their directors' lack of real feeling

for cinematic action-movement of the players. Films impaired by

this failing include The Count of Monte Cristo (1929, with

Jean Angelo and Lil Dagover), Miracle of the Wolves (1924

by Raymond Bernard), The Chess Player (1926 same director),

Violets Imperial (1924, by Henri Roussell, with Raquel

Meller), and even Léonce Perret's renowned version of Pierre

Benoit's novel, Konigsmark (1924, with Huguette Duflos).

As Paul Rotha wrote, referring to some of the above, "Although

pictorially the big realizations seldom fail to please, their

paucity of action often renders them depressing."

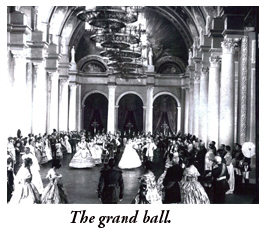

`Showy and rather pointless cameracrobatics introduce the Grand

Ball at the Czar's palace with a tracking shot from the orchestra

and an effect since claimed as a Busby Berkeley special - the camera looking virtually downwards upon the dancers.

More impressive is the straight long shot of the magnificent ball

room. The Czar is introduced by title and mid shot. Two men are

next shown in the gallery, each with a tracking close-up - one

up to a big C.S. of his eyes, the other up to a big C.S. of his

ear. They see and hear a General approach the Czar with news of

the Tartar rising. This is well done but rather too subtle in

the abridged version, though a faithful copy of the book. Next,

by visiting cards, Jolivet and Blount are introduced.

special - the camera looking virtually downwards upon the dancers.

More impressive is the straight long shot of the magnificent ball

room. The Czar is introduced by title and mid shot. Two men are

next shown in the gallery, each with a tracking close-up - one

up to a big C.S. of his eyes, the other up to a big C.S. of his

ear. They see and hear a General approach the Czar with news of

the Tartar rising. This is well done but rather too subtle in

the abridged version, though a faithful copy of the book. Next,

by visiting cards, Jolivet and Blount are introduced.

A finely-lit long shot shows General Kissoff with the Czar in

his room. Titles explain the threat to Irkutsk of the traitor

Ivan Ogareff and the Tartar Feofar Khan, and, since the safety

of Irkutsk is desperately important, a Courier is summoned. The

Czar leans over a map, his finger on Irkutsk. His thoughts run

on the menacing Tartars. Then spacious long shots show a Tartar

horde riding down a peaceful Russian village leaving their marks

of murder, rape and pillage. Intercut are close-ups of the Czar,

shot with pale-fringed vignette. The sequence is worked up as

the noise of the band and the dancers stir up the troubled rhythm

of his thoughts, but the mechanics of the cutting are obtrusive

which weakens the effect. In long-shot, the dance ends. In mid-shot,

with titles, Blount and Jolivet decide to follow the Tartar revolt

in Siberia.

Michael Strogoff is impressively introduced as he enters the Czar's

room, and titles explain his mission. His rather dandy make-up

is, of course, to offset his later toughness and is merely a pleasurable

prologue to a struggle as far as his fans are concerned. His uniform

and bearing are beyond reproach. He strides out and away in a

long shot with immense depth of focus and a nice effect of light

streaming in through the huge doors: fade out.

On a small paddle steamer on the Volga the reporters reappear,

and Strogoff (now the standard Ivan Mosjoukine, clean shaven),

travels incognito as Nicolas Korpanoff - and has met Nadia, also

en route to Irkutsk to rejoin her exiled father. A series of mixes

culminate in C.S. of the Tzigane dancer, Sangarre, with a tambourine.

Ogareff is introduced. He is posing as one of the troupe in an

act with a performing bear. Then, seated on the deck, Michael

and Nadia overhear a conversation between them. The wording comes

literally from the book

"It is said that a courier has set out from the Czar for

Irkutsk."

"It is so said, Sangarre, but either this courier will arrive

too late, or he will not arrive at all."

A white-fringed C.S. of Strogoff is intercut. The coincidence

of the overhearing is glossed over satisfactorily.

A title introduces the Posthouse at Ishim, Siberia. A traveler

drives up, demands horses, and is told they are already booked.

He enters, and in long shot within we see him come - Strogoff,

Nadia, Blount and Jolivet being present. Then, terse and brilliant

in every phase of filmcraft:

a. L.S. The postmaster indicates who has booked the horses

b. C.S. Strogoff moves slightly forward

c. M.S. Man stares, turns to postmaster (Blount in background).

d. C.S. Nadia looks from postmaster to man, apprehensively

e. M.S. (track forward) Man strides up to Strogoff, says

f. TITLE "I must have your horses."

g. C.S. Strogoff replies

h. TITLE "You may not."

i. CM.S. Man strikes him with whip

j. C.S. Nadia is horrified

k. C.S. Strogoff stares without speaking, at

l. C.S. (diffused) the Man - MIX TO

m. L.S. (track forward) the Czar in his room

n. C.S. Strogoff calmly shakes his head, says

o. TITLE "I shan't fight."

p. C.S. Nadia looks at him

q. L.S. Blount, Jolivet, and the Man stride from the room

r. C.S. Nadia thinks - MIX TO moving light pattern - MIX TO

s. CM.S. Strogoff overhearing Ogareff's conversation; superimposed

title, Un courier du Tzar est parti de Moscou pour Irkoutsk

- MIX TO moving light pattern - MIX TO

t. C.S. Nadia thinks.

u. L.S. She sits down by Michael, says

v. TITLE "Brother, I do not doubt your courage."

w. C.S. He looks up

x. C.S. She smiles down at him

y. C.S. He gets up, his bearing restored

z. L.S. He stands erect by her - FADE OUT

The tautness, the concise dramatic narrative-content of

the shots is clear from the scenario. Prominent among the touches

of finesse in their direction, photography, acting, and montage

are: Blount's natural entry, background of (a) . . . the slight

but meaningful movement at the end of otherwise static (b) . .

. the grouping, and the lighting (including the view through the

window) in (c) . . . the anxious movement of Nathalie Kovanko's

eyes in (d) . . . the compositional perfection of (e) where the

speed of tracking forward and the diagonal direction are so chosen

that the Man, striding forward, always remains at the side of

the frame . . . Nadia becomes at the apex of a triangular composition

- and the perfectly timed cut, after the blow, to Nadia's reaction

close-up (j) . . . (k) is full of suppressed fury, but (l) and

(m) precisely convey the Czar's warning - and the arrangement

(r), (s), (t) is inexpressibly well done. (The version available

contains a translation in the middle of (s) which is redundant,

breaks the rhythm of the weaving lights, and should be removed.)

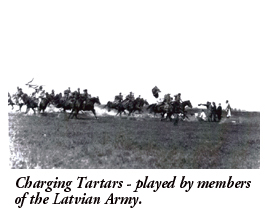

The attack by the Tartars on the

ferry is magnificently done with grim detail. Strogoff fights

valiantly, is finally shot, and falls overboard. The Tartar types

are admirably chosen, being shown in detailed close-ups during

the fight. Nadia becomes their prisoner. An excellently turbulent

close-up shows the wounded Strogoff caught in the strong current,

and he finally collapses among the reeds by the river bank.

The attack by the Tartars on the

ferry is magnificently done with grim detail. Strogoff fights

valiantly, is finally shot, and falls overboard. The Tartar types

are admirably chosen, being shown in detailed close-ups during

the fight. Nadia becomes their prisoner. An excellently turbulent

close-up shows the wounded Strogoff caught in the strong current,

and he finally collapses among the reeds by the river bank.

The short sequence in the Mujik's hut is notable for the excellence

of the photographic composition of the interiors, and for the

fine bearing of the unnamed player who plays the Mujik. The cutting

of Strogoff's symbolic dream, wherein he struggled to climb a

vast stair, is most regrettable. Strogoff, now quite handsomely

bearded, renders thanks and strides away from the haven. This

beard is a satisfactory break-away from the convention that permitted

(for example) Edward Malone (Lloyd Hughes) to be clean-shaven

after days in The Lost World.

At Omsk, preparations for the Tartar attack are indicated by a

spacious long shot. Marfa Strogoff is introduced in a large room

of her house apparently praying for the safety of the besieged

town. She is shown in a well-arranged close-up,with circular vignette.

Strogoff passes through the battle zone to reach the town. The

battle scenes are superbly done on a huge scale. Details of the

leaders are cut in which heightens the realism. The detail shots

of the padre and the bearer of the standard who are shot down

are well taken from a low angle with strong dramatic emphasis.

The triumphal charge of the Tartars, their entry through the gates

of Omsk, the panic of the civilians, and the occupying Tartar

column riding past a burning building are shown in long shots

crammed with turbulent action - vigorous, impressive, and highly

dramatic. (There is an air of newsreel realism, unusual and hard

to explain. The abbreviation weakens the effect by making things

happen too quickly.)

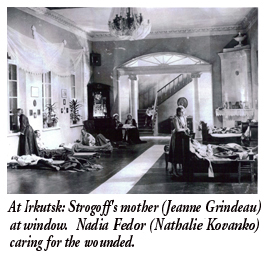

At night, Strogoff looks through the window to get a glimpse of

his mother. Four superbly arranged and lit shots, intercut, narrate

this action: a fine L.S. of the house and street, a vividly real

shot through the window showing Marfa tending the wounded, a slightly

over-pathetic close-up of Strogoff looking in, and a detail C.S.

of Marfa looking up. The shots are fine in content but, strictly

faulty in camera-angle since the second shows a window-frame which

Strogoff was too near to see, and the third is taken from inside

the window which draws attention to an "impossible"

camera position. Strogoff walks away, but a horseman has noted

the incident. As in the book, Strogoff's lapse is shown as a grave

blunder.

The café set is another gem. Strogoff's denial to Marfa,

the hurried exit, shaving with a splinter of glass, and a getaway

on the white horse are done in fine style with bold black and

white lighting. The background of drunken Tartars in the café

is another studied detail. Marfa is questioned again in Ogareff's

huge apartment in which crude disorderliness is well conveyed.

The Marfa-Ogareff "struggle" close-up of extreme power

is shot with pinpoint sharpness of focus against a very diffused

background. The exterior night scenes of Strogoff pursued, riding

through the dark woods and exchanging his horse for the mount

of a shot Tartar are really superb. At dawn the Tartars still

chase the lone white horse. They are in the battle region, and

Strogoff is in the telegraph office with Blount and Jolivet. The

former wires leisurely at 10 copecks a word while Jolivet prances

about in impatience. A picture of the Czar adorns the wall. The

clerk is imperturbable. The Tartars approach. Jolivet lures Blount

to the window, starts writing, pauses to fling out a shell that

comes through the window. It explodes outside partly wrecking

the office (a crisp piece of cutting). Jolivet continues writing

Then a queer streak of over-sentimentality intrudes. The white

horse walks up, and collapses, and Strogoff is still kneeling

by it when the Tartars come up and capture him.

Marfa and Nadia have met also as prisoners. At Ogareff's command

the former is forced to kneel at the point of a sabre to be flogged

till she points out her son amongst the prisoners. Here the presentation

is straight-forward but with the unusual attention to detail.

Sangarre nudges Ogareff. There follows a masked C.S. of Strogoff,

then a C.S. of his hands clenched behind him. In a sudden turmoil

of action, Ogareff gives the word. The Tartar raises the knout,

Strogoff dashes forward, and hurls him aside. Ogareff strides

up, and in two magnificently vivid close-ups, Strogoff furiously

swings the knout and smashes it into Ogareff's face. A score of

Tartars close in, and the Czar's dispatch is seized and read

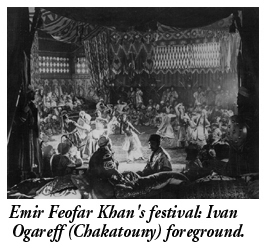

At the Emir Feofar Khan's huge festival, established in vast long

shot with flags topping the frame in the foreground, Ogareff brings

his news, and Strogoff awaits sentence. Fanfares and dancing and

acrobatic riding abound. The Emir announces the penalty of blinding.

The gauze-fringed close-up emphasises the cruel lines of his face.

Nadia is swept back into the crowd. Marfa stands near. A sabre

is heated on a huge brazier. The dancers become more abandoned.

Marfa cries bitterly. Strogoff stands calm. Nadia stands deathly

still. A tear can be seen in Strogoff's eyes, as he looks towards

his mother. The red-hot sabre is raised in a grim close-up. Then

comes flashes of the dancers, of Nadia's grief, of Marfa collapsing.

Then a close-up of Strogoff writhing in pain, his eyes horribly

burned. The huge crowds disperse. Ogareff cuts the cords and gives

his victim a last contemptuous kick. Nadia rushes forward. The

three are left alone, and Michael is helped across to Marfa in

a long shot of the empty dais. He whispers to her, and she smiles.

Those who know the book remember his explanation to her of the

miracle that has saved his sight.

Wassili Fedor's pardon by the Grand Duke at Irkusk is mutilated

to a series of too short shots and one vast subtitle.

In a hut, Nadia and Michael rest. He grieves at hindering her.

A thin streak of blood from his left eye is the reminder of his

fate. In two lovely close-ups, free from exaggeration, a tear

falls from Nadia's eyes on to their cupped hands.

At Irkutsk Ogareff announces himself as Strogoff, delivers the

despatch to the Grand Duke, and secures a position in the Palace.

The snow sequence is rather ludicrous. Michael and Nadia toil

on, Nadia falls asleep in his arms, and then (as in the book)

he strides forward the quicker. But the precipice routine is rather

silly. Unhappily, the more dramatic episodes of the later stage

of the journey have been cut. This has also caused Strogoff's

motive for appearing blind, that he  may

be no further molested, to lack conviction.

may

be no further molested, to lack conviction.

Sangarre receives Ogareff's (mis-spelt) note under the ramparts

of Irkutsk. Naptha is seen floating down the river. At midnight

Ogareff drops a flaming torch, and a sheet of flame rises from

the waters. Tartar cannon open fire. There is confusion at the

Palace. Michael and Nadia are seen approaching. It must be admitted

that the foregoing is impossible to comprehend at first viewing

so excessive has the pruning been. The naptha on the swift waters

of the river is a mere flash. The sudden appearance of M. and

N. within the besieged town is disconcerting. Their journey on

an ice-floe over the burning river amid Tartar fire is a real

thrill in the book (reading it recalls Lillian Gish in Griffith's

Way Down East). The shots of the town, seen over the blazing

river, are grandly realistic.

The fight is magnificent. Ogareff treacherously sneaks behind

the blind man. On being countered, he realises the truth - a full

C.S. of Michael's eyes, gauze-fringed. Ogareff attacks with sabre;

Strogoff parries with his short Siberian knife. A superb close-up

has the crossed shadows of these weapons on Strogoff's face. The

traitor's sabre is broken. He feels for a pistol. Strogoff throws

his knife and, gruesomely, pins his hand to the table. Then, springing

from the stairs, a heavy rough-and-tumble follows. Nadia is locked

in the next room. The door slowly opens. It is Ogareff who staggers

in, but collapses. Then Michael comes. Covered with blood, and

with tattered clothes, he still retains dignity and only says,

"God is with us, Nadia." This is simple, restrained,

and most effective.

The discomfiture of the arrested Sangarre on beholding Strogoff

is well conveyed in a telling close-up. The Duke congratulates

the Courier. The Tartars are repulsed and Fedor and Nadia reunited

in grand exterior night scenes in the snow.

The setting for Michael's introduction is exactly repeated, but

in front of exalted guests, as the Czar promotes him to Colonel.

Unhappily, the sequence ends with iris-out on the dandy Strogoff

taken from an angle that fails to do him justice. One recalls

that he is at his best full-face.

Blount and Jolivet are present in the bride's home when, according

to custom, the relatives give the betrothed couple (kneeling)

their blessings before the church ceremony. The lighting of the

long shot is beautiful. Marfa and Wassili are together. Then the

Cathedral towers are seen, bell tolling, and a really lovely long

shot in the Cathedral with faint sunbeams. Nadia makes a sweetly

pretty bride, and Blount and Jolivet are still in attendance as

Michael embraces her, takes the candles, and extinguishes them:

slow fade-out.

SCENARIO:

The sustained dramatic balance is remarkable, and the narrative

value as expressed in film form is excellent.

DIRECTION:

The only faults one can find are the two over-emphasised touches

of sentimentality and the tendency to digress into spectacle.

The Trade reviewer rightly remarked, "We understand that

since the trade show at the Albert Hall the film has been re-edited,

and we have no doubt that, with some curtailment of merely spectacular

effects and elimination of some of the blood and brutality, a

strong, dramatic story by a master hand, superbly presented, will

be enthusiastically received by every class of audiences."

Of the many strong directorial touches, the fine scene at Ishim

and the details selected in the fight sequences stand out. In

the handling of the players, too, routine gestures have been avoided.

CONTINUITY:

The story of its nature tends to be episodic, but small touches,

as the decreasing orderliness of Nadia's hair as she gets further

on her journey, are carefully controlled.

PHOTOGRAPHY:

Notable for thoughtful masking, for excellent collaboration with

the director in the Ishim sequence, and for the remarkable brilliance

in most of the exteriors. Parts of the original were hand-tinted

in two or three colours, as were parts of the contemporary Italian

Last Days of Pompeii.

ACTING:

This is really beyond reproach. To realise to the full the fine

characterisations of these excellent players, one has only to

compare them with the costumed marionettes of other films. As

a team they achieved the epic realism of The Covered Wagon.

MONTAGE:

The cutting of the original was too leisurely. Only certain sequences

are notable. The cross-cutting at the Ball fails due to visible

mechanics. However, the timing of the intercut detail close-ups

in the fight scenes is excellent.

DESIGN:

The settings of the period from the Mujik's hut to the Grand Palace,

have been designed and reproduced with detailed accuracy and a

careful eye to dramatic composition (e.g. at Ishim).

GENERAL:

Michael Strogoff is probably the best adventure story of the heroic

type, based on a struggle theme, in the whole history of the silent

film. Even the much-abridged version available will never fail

to impress an audience when properly presented with a first-class

musical accompaniment. Fresh air blows across its magnificent

canvas; lofty mountains and wide rivers lie along the memorable

journey: a nation fights and conquers an aggressor: the hero's

romance is fittingly fulfilled in the Cathedral.

Notes:

- The Chess Player has been acclaimed a masterpiece since its restoration and release on DVD

- Despite Anthony Bulleid's dismissal of The Grand Ball, I consider the intercutting between the aristocrats dancing and the Tartar cavalry charging among the finest sequences of French (or Russian) cinema.

- Tina de Yzarduy was Raquel Meller's sister.

- The film has now been restored by the Cinémathèque Française, complete with stencil colour, but they have no plans to release it on DVD.

- With grateful thanks to Lenny Borger for corrections to this article.