A trackless, barren expanse of sand left by the receding of ancient

Lake Lahontan some 12,000 years ago, the Black Rock Desert stretches

for more than a hundred miles across the vastness of northwestern

Nevada. Ancient peoples first occupied the area 7,000 years ago,

and their descendants were still there when Captain John C. Fremont

and his men came down High Rock Canyon in late December, 1843,

to become the first outsiders to lay eyes on the large playa.

Clarence King's Fortieth Parallel Survey mapped the southern section in 1867, and Israel C. Russell of the U.S. Geological Survey extended the work to the northern part in the early 1880s, producing a monograph which has become the basis for all subsequent studies.

Overland immigrant parties passing west on the Applegate-Lassen Trail in the 1840s and 1850s knew the rigors of the Black Rock, as did horse soldiers operating out of Fort Churchill during the Civil War. A brief silver mining flurry led to the establishment of the camp of Hardin City on the north end of the Black Rock in 1866, but the mining of sulphur has been the principal economic activity in the area in recent decades.

In November of 1909, the construction of the Western Pacific Railroad across the southern end was completed, l but the oddest bit of history associated with the Black Rock Desert is the filming of "The Winning of Barbara Worth" near Trego on the southern end during the summer of 1926.

Based upon Harold Bell Wright's best-selling saga of the reclamation and settlement of California's Salton Sink, "Barbara Worth" was the third in a series of classic silent westerns filmed in Nevada during the 1920s. Both "The Covered Wagon" (1923), shot on location at Skull Valley in White Pine County, and John Ford's "The Iron Horse" (1924), filmed at Dodge Flat, just north of Wadsworth, were received with popular and critical acclaim, proving to other producers that the "big western" was no mere flash in the pan. (2)

Wright's novel had cast the settlers of the Salton Sink as 20th-century pioneers, and Samuel Goldwyn himself, producer of "Barbara Worth," spoke of his film as "taking up the history of the West where 'The Covered Wagon' leaves off."

As adapted for the screen by Francis Marion, however, the production became a showcase to exploit the appeal of Ronald Colman and Vilma Banky, whose appearance in Goldwyn's "The Dark Angel" in 1925 created Hollywood's first "love team."

Goldwyn also had loftier pretensions. In an interview with Grace Kingsley of the Los Angeles Times on June 18, 1926, he asserted that the success of "The Covered Wagon" demonstrated the popular interest in films of more substance than the general run of western productions up to that time, "something educational if it is made entertaining," as he put it.

"'Barbara Worth' will be a great epic," he predicted. "It shows and proves what a great menace the desert can be without water, if not properly controlled by dams. In this picture will be shown an entire town swept away because of the faulty dam construction. The menace of the elements is a real life problem of everyday and 10 times more impressive to people than the menace of all the villains who every played in pictures." (3)

Goldwyn was also interested in a realistic location for filming, as was his director, Henry King, who had traveled to Italy to produce "The White Sister" (1925) and "Romola" (1923), and had ridden out Atlantic storms aboard ship for 17 days to get footage for Fury, a tale of the sea.

In his interview with Grace Kingsley, Goldwyn said that he had chosen the Black Rock Desert because of its resemblance to the Salton Sink, but it was Henry King and two associates--Rostin Clampitt and Robert McIntire--who did the leg work to select the site.

In February of 1926, they had set out on a 4,000-mile trip through southern California, Arizona and New Mexico. But they were still looking for a suitable film location when they debarked at the Southern Pacific Railroad depot in Reno on April 14.

After talking with some locals familiar with the desert country to the north, King decided to rent an automobile and take a jaunt out to the 40-Mile Desert between Wadsworth and Lovelock. Departing the next morning, they looked the area over and went into Lovelock. King decided to push on to Jungo before dark, but the men got lost near Haystack Butte and spent the night driving around aimlessly.

At daybreak, they found themselves at Sulphur, west of Jungo on the Western Pacific Railroad, where the cook for a railroad crew invited them to breakfast on pork and beans before they set out west for Gerlach. Their radiator boiled over just outside of Trego, but the only water they could find was a thermal spring so hot that their driver burned his hands. Cooling enough water in an old washtub they found, they finally filled the radiator and got on their way, arriving at Gerlach at 10:30 that night with only one can of beans and two swallows of water between them. After finding lodging for the night in the small railroad community, they ate dinner.

Early the next morning, they drove 10 miles out on the Black Rock, returning to Gerlach by way of Trego. King was impressed with the location possibilities, and Gerlach had all the facilities and accommodations the large film crew would require. Sending the car back to Reno with their driver, they caught the Western Pacific for Oakland that evening and were back in Hollywood two days later. (4)

Shortly after King's return, Goldwyn contacted the Winnemucca Chamber of Commerce and Winnemucca Mayor Carlton E. Haviland for assistance in finding office space and scouting out likely filming locations near the community. H. C. Oastler, manager of the American Theatre, offered to take care of other details, and Lovelock rancher W. H. Cooper was contacted about furnishing livestock, horses, pack mules and burros for the production. (5)

The June 7 edition of the Humboldt Star announced the expected arrival of the film crew and gave more details of the picture. Three false-front cities were to be constructed-one at Trego, to be known as Barbara Worth, another at the sand dunes, near Blue Mountain west of Winnemucca, and a third at Gerlach.

King was planning on a location time of six to eight weeks, according to the Star story, and had already made contacts in town to rent 25 farm wagons and buggies and several large freight wagons. Editor Stanley Bailey also announced that he and United Artists publicity director H. F. Arnold would begin publishing the Barbara Worth Times, a semi-weekly supplement to the Star, on June 25." (6)

King and four associates--Karl Borg, art director; Friend

Baker, cameraman; Edward Sowders, King's assistant; and Lewis

King, the director's brother--arrived in Winnemucca the next day.

Lewis King remained behind to hold a press conference while the

others caught a Western Pacific special west to Trego where lumber

was being unloaded to begin  construction

on the film city.

construction

on the film city.

Thanking the people of Winnemucca for their cooperation, he announced that he had set up an office in the Hotel Humboldt to interview locals who would be interested in a few weeks of work as extras on the set. Forty to 50 men, women and children would be needed for the initial work, he said, and as many as 300 later on. (7)

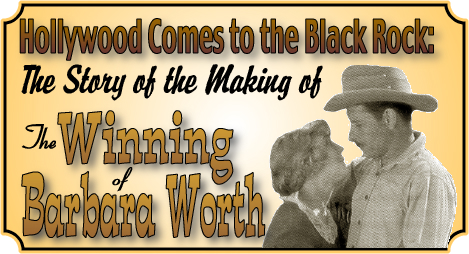

W. H. Cooper had meanwhile been making contacts with several Lovelock ranchers to hire horses and purchase feed. He had also been as far east as Battle Mountain seeking livestock and had been arranging to rent wagons, carts and buggies. On June 10, the Star carried a notice that he was also seeking farm animals--hogs, goats, chickens, cows with calves, mares with colts and horse teams--and wagons in poor condition. (8) (Photo at right: Pershing, Humboldt, and Lander County ranchers provided most of the livestock, wagons and other transportation rigs needed for "The Winnning of Barbara Worth." -- Photo courtesy of the author)

Goldwyn had completed casting by that time, with the exception of the second lead, Abe Lee, a role which was to go to Gary Cooper a few days before filming began.

Neither Ronald Colman nor Miss Banky was enthusiastic about coming to Nevada. Colman had just completed "Beau Geste" at an isolated desert location in Arizona, and his co-star had only recently returned from the making of Son of the Sheik with Rudolph Valentino. However, United Artists had both of them under contract, and they had no choice in the matter. (9)

The carpenters, plumbers and other set-construction personnel left Los Angeles by rail for San Francisco on June 11. Transferring to the Western Pacific at Oakland the next day, they arrived in Gerlach on June 13. Part of the crew remained in town to begin the construction of false fronts on the buildings to be used in the film segments shot there, while the remainder motored out to Trego to start work on sets, buildings and dining and sleeping facilities.

Western Pacific laborers were putting in new water mains at Gerlach for the flood sequences, and railroad officials announced on June 16 that Luthur Greybanc had been appointed station agent for the new movie town at Trego. Sidetracking had been completed by that time, and the carpenters were at work nailing up the prefabricated building sections which had been cut to specification in Oakland. (10)

In Lovelock, rancher Cooper had arranged for the renting of 50 horses from Ray Clemmens, F. B. Salinas and B. A. Preston. He also secured 25 Fresno scrapers and 20 wagons of various types in the valley. P. A. Quigley sold 100 tons of hay to Cooper for the livestock to be used in the film. Several men from Lovelock got work as extras, among them P. H. Wolf, W. H. Orton, Jack Wycoffe, Ray Cahill, Lawrence Lang, Joey Olaeta and Virgil and Albert Smith.

Pershing County officials appointed three men--E. A. Perez, Wilbur Springer and W. H. Cooper himself--as deputy sheriffs at Barbara Worth since the location site was just inside the northern boundary of their jurisdiction. United Artists officials agreed to pay the men $4.50 of their $5-a-day salary, with the county picking up the remainder. (11)

Barbara Worth had taken on all the trappings of a frontier community when editor Bailey of the Star came out on June 18. He noted that a hundred head of cattle and several dozen horses had been brought out, as had horse-drawn conveyances of every description. Thirty-five extras from Winnemucca and Lovelock were also on hand, and the stars and technical personnel from Hollywood were scheduled to be in town within a day or so.

Henry King had named himself mayor of the town, Bailey reported, and had appointed other company personnel as city councilmen. Their first official act on June 18 was a resolution supporting the rules drawn up by camp manager I. N. Liner: no liquor or profane language, quiet after 10 p.m., meals in the mess tent only and no visitations of men and women to each other's quarters. Liner also laid down strictures regarding the conservation of water, keeping horses outside the living areas and the reporting of all illnesses and injuries to the infirmary. (12)

A postal facility was also established at Barbara Worth, as was a bank and an office for the Barbara Worth Times. Extras and other film personnel were housed in large tents, and every effort was made to assure their comfort and safety. Dr. L. A. Eshman, a Los Angeles physician, had been bought up to establish a clinic. Director King also hired H. S. Anderson, a San Francisco chef, to supervise the commissary and prepare meals.

Portable generators provided electrical power. There were also showers and a recreation tent complete with books, radios, phonographs, records and projection equipment for showing motion pictures and the clips from the current film which were to be sent to the DeMille Studio in Los Angeles for developing. (13)

Although Winnemucca, Lovelock and Gerlach supplied all the extras for the initial filming, word that there was work at Barbara Worth spread to Reno. On June 16, an unemployed Reno laborer, A. S. Gorman, and his son, Ray, set out afoot for Gerlach. They became lost somewhere north of Pyramid Lake and wandered for three days without food before reaching Black Sulphur Springs near Sheep Pass. They got their bearings at the springs and stumbled into Barbara Worth on June 19 where Dr. Eshman treated them for exhaustion and exposure.

Three carpenters from the film city had a similar experience when their car broke down on a trip to Sulphur. They had neither food nor water with them and spent two nights and a day wandering in the Pahsupp Mountains. They found water at an abandoned sheep camp, and two of them continued on until they finally spotted Barbara Worth from the top of a mountain. When they came in, they could neither eat nor drink for several hours. One of them finally recovered sufficiently to accompany a deputy sheriff in an automobile to rescue the third man. When found 20 miles out, he was thirsty, hungry and exhausted but otherwise in fair condition. (14)

Goldwyn and King arrived at Barbara Worth on June 21 with

Miss Banky, Colman, Gary Cooper and the remainder of the cast.

The entire 150-man production unit accompanied them, as did technicians

and carpenters from Gerlach where work on preparing the sets was

almost complete.

Goldwyn, King and the others found the accommodations much to their liking. The well to provide hot water had been completed by that time, and laborers laid the last section of pipe into camp that day. Camp manager Liner had tested the water when the well came in and found it to be too salty and brackish for drinking. So he had arranged with railroad officials to haul water in at a cost of $150 a tanker.

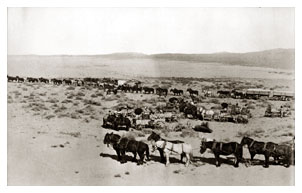

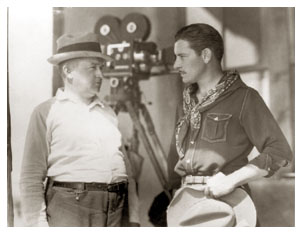

In spite of camp rules, liquor was readily available at Barbara Worth until Goldwyn and King arrived. Taking stock of the situation at that time, they contacted Nevada Prohibition Administrator George Brady and had him station two of his agents at the movie camp. Barbara Worth was officially "dry" thereafter, but a Lovelock resident who worked as a teamster during the filming once told this writer that members of the cast had their own private stocks or were able to arrange for deliveries from Reno and Gerlach. (15) (Photo at left: Director Henry King, left, and producer Samuel Goldwyn inpsect a stagecoach during a visit by the producer to the movie location. - Photo courtesy of the author)

Henry King had planned on filming the first scenes on June 20, but set changes and costume alterations ordered by art director Borg moved the date up to June 21. A crowd of spectators from Winnemucca joined the extras on the set that afternoon, and some of them were hired on the spot to be part of a street scene which included a wagon train, settlers, Mexicans and cowboys, but disaster struck right off. A wagon overturned on a grade at the edge of town when the horses spooked, spilling six extras out in the dirt. The driver was taken to the infirmary to be examined by Dr. Eshman, but he was pronounced fit after he regained consciousness two hours later.

A sandstorm added a touch of realism the next day. King saw it coming and ordered a camera crew out in an automobile to chase it across the desert. The Barbara Hotel, largest of the false-front structures, blew down as the cameras of another crew rolled, as did the laundry, the general store, the barber shop and most of the tents. Barrels, tenting, clothing and everything else that was not nailed down blew out across the desert. However, King was delighted with the footage and was making plans to incorporate it into the final cut.

A few minutes later, a cloudburst struck, drenching everyone to the bone and washing out the road to Gerlach, the company's main supply line. King told a newsman on the scene that production would be set back 10 days, but he was able to resume work three days later. (16)

The first edition of the Barbara Worth Times appeared as a supplement to the Humboldt Star on the day of the storm. Edited by Colman and Miss Banky, the paper related the news that she had made a pet of a desert chipmunk which had wandered into camp. Another story told of the arrival of chef Anderson at 5 a.m. on June 19 and of the heroics of his crew in getting set up and preparing breakfast for several hundred hungry actors, carpenters and extras within two hours. (17)

The heat was becoming unbearable by the second week of filming -- l24 degrees recorded in the commissary tent one afternoon--and the Barbara Worth Times of July 1 carried the news that King had decided to begin filming no later than 5 a.m. The actors, cameramen and technicians would have to get up at 4 a.m. to meet that schedule, so King and the members of the governing body of the town issued an order imposing a 9 p.m. bedtime curfew. Four dissenting votes were registered at the meeting called on June 29 to consider the matter. However, the motion carried, and a night watchman was hired to enforce it.

The musicians brought up from Hollywood to provide background music had begun to offer nightly concerts by that time. Many of the visitors and tourists who came out to watch the filming stayed for the nightly performances and camped out on the edge of town. Several actors were reported to be taking guitar lessons from the cowboys hired as extras. But Colman remained in his tent most evenings listening to records, and Miss Banky spent her free time next to her radio.

In nearby Gerlach, George Mosher, manager of the town's baseball team, challenged the movie folks to a game on July 4. King had decided not to film that day, so a team was hurriedly put together which took the measure of the railroaders by a score of 8 to 7.

Gerlach's constable, Henry Hughes, had become a popular figure with the California visitors, regaling them nightly with tales of the "wild West" and stories of men who had "died with their boots on." Director King was particularly interested in the nightly sessions, as were the screen writers who were gathering material for future projects by talking to cowboys, prospectors and other desert dwellers hired as extras. (18)

On June 21, Harry Chandler Jr., son of the publisher of

the Los Angeles Times, paid a visit to Barbara Worth. He and his

father had a financial interest in the production, he told a newsman,

and he spoke highly of the cooperation of Winnemucca and Gerlach

businessmen.

The editor of Motion Picture Magazine also spent some time

at Barbara Worth that summer. He was somewhat unnerved by the

vicious heat and the blinding sandstorms but fascinated by the

men who had been hired as extras. "At night they gave us

a real picture show and all the citizens were present," he

wrote. "And such citizens! Most of them were natives of the

surrounding country, all carefully selected by Henry King. It

was a great sight to see them all huddled together on the floor

watching themselves on the screen. There were mountaineers, cowboys,

Indians, trappers and ranchers of every description and all in

all, the queerest looking specimens I have ever encountered. They

not only looked and acted their part they were the part."

(19)

On July 6, tragedy struck again when Walter Ordson, an assistant cook, accidentally set the commissary tent on fire while he was filling some gasoline lanterns. The flames spread to a large sleeping tent and two canvas shelters being used for the storage of supplies.

Ordson sounded the fire alarm, organized a bucket brigade on the spot and managed to check the conflagration, but the commissary tent and the sleeping quarters were leveled. Abraham Lehr, commissary manager, managed to get the foodstuffs out, but the loss of the tents set the company back some $10,000.

The fire, winds and floods hardly daunted King's enthusiasm, however, and the Barbara Worth Times of July 8 reported that he had recently sent a crew out to film another sandstorm sweeping across the Black Rock fives miles to the north. (20)

There was also the usual run of illnesses, accidents and other untoward occurrences during the making of the film. On June 24, Tom Loy, an Indian, lost control of his horses during a scene, and the wagon being pulled by them went careening madly through the streets as the cameramen continued filming as though the runaway were a part of the script.

Walter E. Tregaskis, a Denio cowboy who had been hired as an extra, came into Winnemucca on July 8 where he tried to purchase some narcotics at a local drugstore. When the pharmacist refused his request, he threatened to kill himself on the spot. A deputy sheriff, who happened to be in the store, took him into custody and hauled him off to the police station. But Tregaskis grabbed a length of pipe during the booking and tried to assault Police Chief N. .P. Moore. Other officers subdued him, but he tore up his cell a few minutes later. At a hearing the next morning, Judge L. O. Hawkins ordered that he be taken to the state mental hospital in Reno for further evaluation.

A Winnemucca youth, Paul Koseris, fell from a porch on July 15. Dr. Eshman found no broken bones when he examined him a few minutes later. But he was taken with chills, fever and chest pains that night, so arrangements were made to rush him to Winnemucca on a scheduled freight train a few hours later. He was hospitalized for several days before being sent home and was able to be out and about within two weeks.

Bill Patton, a stunt man injured in a fall on July 19, spent eight days at the Winnemucca hospital also. (21)

Miss Banky took a break from filming on July 6 to return to Hollywood for the opening of "The Son of the Sheik" at the Million Dollar Theatre on July 8, but work on the picture was proceeding on schedule.

Lewis King was back in Winnemucca on July 12 seeking 30

women and 25 children for the next phase of the production, but

he was unable to find the 75 men he needed to portray settlers.

Later that afternoon, he wired Sam Frankovich of Reno's Frankovich

Employment Agency telling him of his needs. Frankovich sent back

word that he could  provide

the men, so King caught the train for Reno the next morning.

provide

the men, so King caught the train for Reno the next morning.

Several hundred men were on hand at the Wine House on Commercial Row that evening, and King got the pick of the lot--big men, tanned and bewhiskered with scuffed boots, big hats and tattered shirts. They departed for Winnemucca in a special railroad passenger car the next afternoon and were taken out to Barbara Worth on the Western Pacific the next day. (22)

Henry King was meanwhile planning ahead and making preparations for moving the production to the sand dunes at Blue Mountain. Carpentry crews had been sent on ahead to begin construction of a second town, while wagons were being loaded with equipment not needed to complete the work at Barbara Worth. King placed Winnemucca Mayor Carleton E. Haviland, who had been picking up some extra money as a construction superintendent, in charge of the move. The first group of wagons and teamsters moved out for the new location on July 13. (Photo at right: Preparing to film one of many desert scenes. - Photo courtesy of the author)

King also made arrangements to send a crew of performers and cameramen to Devil's Canyon, a remote location 60 miles south of Winnemucca, to film a "bandit ambush" sequence, and to Paradise Valley to shoot footage of developed farms and orchards and fields of alfalfa.

He had also given some thought to the final scene--the marriage of Miss Banky and Ronald Colman--and had his brother contact Father Hugo A. Meisekothen at Winnemucca's St. Paul's Catholic Church about performing the mock ceremony. (23)

Edwin Schallert of the Los Angeles Times ventured out to the desert location just as filming there was winding up. In an article published on July 18, he described the Black Rock as "a desert quite unlike, different, than others," and commended Goldwyn for going to the trouble and expense to find one which had not been "sheiked to death."

Schallert had also seen clips of the film at the DeMille Studio when he returned home. The sweeping distances across the alkali flats and the striking cloud effects particularly impressed him, adding depth and substance to a story line he considered "so commonplace." He also had nothing but praise for the fine performances of Colman and Banky, describing her as "surprisingly American," a comment on her Hungarian nativity. (24)

On July 18, Nevada Governor James G. Scrugham and R. M. Oliver paid a visit to Barbara Worth. They had been in northern Humboldt County examining some opal properties and had decided to drive down the Black Rock and over to Winnemucca from the west rather than coming directly south from Denio. Director King conducted them around the set, and they observed the filming of some final scenes before departing late in the afternoon. (25)

Station agent Greybanc

had previously ordered that several boxcars be left on the siding

at Trego, and a crew was loading them with equipment, supplies

and tenting on the day of Scrugham's visit. Lewis King had rented

trucks in Winnemucca to haul the cargo out to the new location,

and Miss Banky, Colman and other members of the cast were planning

on a short break in town before going out again.

Station agent Greybanc

had previously ordered that several boxcars be left on the siding

at Trego, and a crew was loading them with equipment, supplies

and tenting on the day of Scrugham's visit. Lewis King had rented

trucks in Winnemucca to haul the cargo out to the new location,

and Miss Banky, Colman and other members of the cast were planning

on a short break in town before going out again.

Rooms were reserved at the Hotel Humboldt, but Miss Banky's arrival was delayed until the evening of July 22. Gary Cooper came in on the same train, as did Clyde Cook and Erwin Connelly, comic leads in the film, and E. J. Ratcliffe, a Broadway veteran who played James Greenfall, a New York financier. Colman was delayed by some last-minute takes and rode in with director King the next morning. Cooper was awaiting them, and they only had time for a quick breakfast before departing for Devil's Canyon. (26) (Photo at left: Nevada Governor James G. Scrugham speaks to Vilma Banky and Ronald Colman on his visit to the movie location in July 1926. Director Henry King is at left. - Photo courtesy of the Nevada Historical Society, Reno)

Miss Banky went shopping the morning after her arrival, purchasing a camera, several dresses, shoes and other items of wearing apparel. She spent two hours walking around town snapping pictures and expressed surprise at finding Winnemucca such a pleasant place--paved streets, trees, attractive buildings--not at all what she had been led to expect. She went for an auto ride on the outskirts of town and joined her fellow performers at the American Theatre that evening. As it happened, Clyde Cook had a part in the film the movie house showed that night. (27)

Lewis King remained in town to arrange transportation for

the 100 extras who were going out to Blue Mountain. Miss Banky

and the others left on July 26. Henry King, Colman, Cooper and

the camera crew returned from Devil's Canyon the next morning

and checked into the Hotel Humboldt to catch a few hours of sleep

before continuing on.

In an interview with the editor of the Star shortly after

he got back, King effused over the country he had just come from--good

scenery and lighting, perfect for filming. They had spent the

night at Sweeney's Ranch, he said, completing their trek to the

canyon on horseback and hauling their equipment in by pack mule.

(28)

On August 1, Thomas E. Campbell, former governor of Arizona and chairman of the Federal Board of Surveys, drove out to Blue Mountain from Winnemucca. He had supervised a study of reclamation projects in the West the year before and was interested in the film because it concerned the Imperial Valley and the use of the waters of the Colorado River. Director King showed Campbell around the set, explained the reclamation theme of the film and invited him to spend the night, but he had to return to Winnemucca to catch an evening train. (29)

King wrapped up the filming at Blue Mountain on August 4, and most of the actors and the production crew were back in Winnemucca the next day. Carpenters and technicians were dismantling the makeshift buildings and taking down the lighting by that time.

The cast, crew and extras were on hand for the shooting of the wedding scene at St. Paul's Church on the morning of August 6. A sense of nostalgia and sorrow at splitting up seemed to pervade the ceremony. But most of the performers were reported to be "homesick," and the first contingent left on the Western Pacific that evening. Editor Bailey of the Star was also a bit regretful, observing in his column that day that another "ghost city" was about to be created, a community more deserted than a "busted" mining camp since it was bereft of even those residents who usually stayed on hoping for a revival of the mines. (30)

Lewis King was meanwhile taking care of final details. He had previously advertised for bids on some 200,000 board feet of lumber used in the construction of buildings at Gerlach, Barbara Worth and Blue Mountain. King considered the first offers too low, and it was not until early September that he was able to dispose of the building materials to the Gerlach Land and Livestock Company to be used in the construction of stock corrals, barns and line shacks. A dozen ranch hands showed up on September 11, and the site was cleared by the end of the day.31

The cast took a few days off after returning to Hollywood. Henry King worked on his golf game during the time he was able to spare from working with the film editors. Ronald Colman relaxed aboard a friend's yacht off Catalina Island.

Miss Banky checked into a clinic for an examination of her leg which she had injured when a horse stepped on her during the final day of filming at Blue Mountain. Her doctor could find nothing but a slight bruise, so she motored out to Goldwyn's estate at Del Monte for a few days of rest. On August 18, Goldwyn summoned her and Colman back to the studio to look over the script and costumes for their next film, Night of Love, and they were back at work the next day. (32)

Goldwyn had meanwhile made arrangements for the premiere of "The Winning of Barbara Worth" at the Forum Theatre in Los Angeles on October 14.

John P. Goring, manager of the Forum, was very high on the film, calling it "probably the greatest picture of the West" ever to grace the screen. "I have seen more than 50,000 feet of rushes on this picture," he told a film writer, "and I can honestly state that never in my life have I seen a picture with such a magnificent sweep and such wonderful photography. I believe this picture will more than duplicate the long run of Stella Dallas, and I know that it will be a revelation to Los Angeles theater-goers."

Goldwyn agreed, describing the film as "my most ambitious production" and "the finest thing Henry King has ever done." (33)

Studio publicity focused upon the Colman-Banky romance angle as well as the underlying theme, "the triumph of man over the elements, the transposition of a barren wilderness of sand into fertile fields and orchards," as one release had it.

Henry King was also interested in the "educational possibilities" of the film, one article stated, the weaving of "a tale of romance around the true facts of the pioneering days of the West."

Ronald Colman was not quite as upbeat, telling a reporter that he hoped to see the day when all deserts everywhere would be reclaimed and settled so that he would never again be called upon to make a desert film. (34)

As it happened, the Los Angeles Chamber of Commerce was

hosting a conference of state and federal reclamation officials

at the time of the premiere, so arrangements were made for them

to attend. Among those in the audience that night was Nevada's

governor, James G. Scrugham, who had visited the location earlier

in the summer. Not a seat was empty  for

the opening, and Goring declared the premiere to be the most notable

in the history of his theater.

for

the opening, and Goring declared the premiere to be the most notable

in the history of his theater.

Local critics had nothing but praise for Goldwyn's effort, one of them declaring it to be a milestone in film history, "not alone for its sterling qualities as screen entertainment, but as anew and virile chapter in the cinema's transcription of western history--a chapter none the less alluring because it deals with the present generation. " He praised Goldwyn and King for producing a Western without the usual stock characters and for focusing upon recent history "when men turned their backs on the lure of an El Dorado in the hills and sought the wealth that lies within the soil."

The stars in the film were not overshadowed by the magnificence of the natural setting, he observed, and Miss Banky did surprisingly well as "a western girl", although some viewers might not see her as the heroine portrayed in Wright 's novel. The reviewer lauded Colman for the "easy poise" he showed in his role and praised Gary Cooper and Clyde Cook for their stellar supporting performances. (Photo at right: Nevada Governor James G. Scrugham speaks to Ronal Colman on the set. - Photo courtesy of the Nevada Historical Society, Reno)

But his highest accolades went to Henry King for his decision to film in Nevada and for the genius of the special effects, particularly the final flood scene which he declared to be the finest he had ever witnessed in any production. (35)

Reviewer Edwin Schallert of the Times, who had spent

a few days at Barbara Worth during the filming, felt that the

picture opened up new vistas and established new standards for

the Western. "It affords a vision of new meanings with which

the pictures of western locales must be endowed in the future,"

he wrote, "and in that respect particularly is far reaching."

Like other reviewers, he was struck by Miss Banky's physical attractions

and her wholesome appearance. "Her blond beauty makes her

very American in type," he concluded. "No American girl

could have appeared more completely the American girl than she

did, a Hungarian." (36)

Other critics had mixed reactions. "At times annoying,"

a New York Herald-Tribune writer ventured, "but at

other times it has moments of real beauty." A reviewer for

Picture Play commented that the script and theme lacked

substance, "too little...to have enlisted the fine skill

of Henry King and the talents of Vilma Banky and Ronald Colman.

They are out of their element." (37)

Eastern critics in general were unimpressed. A New York Times writer expressed the opinion that the visual impact of the storm and flood scenes had been "stripped of excitement" by the many desert pictures coming out of Hollywood recently. He credited King with having "a good eye for special effects," but "his comedy, or that of the scenarist, cannot be accused of being especially keen." He characterized the rivalry between the characters played by Colman and Cooper as "struggling along in a rather tedious fashion," and Miss Banky seemed to him "essentially a hothouse flower and not the type one would expect to see living in a desert shack."

Critic Mordaunt Hall of the Times was in agreement. In a December 5 review, she conceded that Miss Banky's "charm" was an asset to her role, but she still found her to be unconvincing ''as a girl who had such tremendous faith in the desert." Goldwyn's hopes of making the film "The Covered Wagon of the desert" had not been realized either, Miss Hall concluded, although the effort was commendable. (38)

On December 7, "Barbara Worth" opened a four-day run at the American Theatre in Winnemucca. Before the first showing, manager H. C. Oastler came on stage to read a telegram from Ronald Colman and Vilma Banky. "We realize that Nevada and especially Winnemucca assisted in making this picture a national success," the wire read, "and the wonderful cooperation given us is deeply appreciated."

Among those in the audience that night were many of the extras who had worked on the film and others who had rented equipment or livestock to the company. They had nothing but praise for the picture, and editor Bailey of the Star felt that it would show viewers elsewhere what could be accomplished by "dreaming and fighting." He also expressed the opinion that it would help Easterners understand the "possibilities" of the West and lessen opposition in Congress to the further appropriation of funds for the reclamation of desert lands. (39)

Film historians praise the documentary reconstruction of history embodied in the film, rating it with the two Western epics which preceded it. The movie is still preserved in the archives of Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer and is still shown to students of the film art.

European film writers have also accorded high praise to the film. In France, where it became Barbara: Fille du Desert, one critic has rated it as more significant than either The Covered Wagon or The Iron Horse. (40)

Samuel Goldwyn teamed Colman and Banky in three subsequent love stories - "Night of Love" and "The Magic Flame," both released in 1927, and "Two Lovers," 1928. Miss Banky also made "The Awakening," without Colman, in 1928.

The sound era had arrived by that time, and Goldwyn featured Banky in her first speaking role in "This is Heaven," which had its premiere in May of 1929. Her foreign accent made her practically unintelligible in front of the sound camera, however, and her performance earned her "laughs rather than heart flutters," as one writer put it. The film was a disaster at the box office, and Goldwyn decided not to use her again, paying her the remaining salary stipulated in her contract--$250,000.

Miss Banky married actor Rod LaRoque that year and made one more American film - "A Lady to Love" in 1930. It got some European circulation in the German version, "Die Sehnsught Jeder Frau." In 1932, she starred in a German production, "Der Rebell," her last effort on the screen. The marriage to LaRoque lasted until his death in 1969, and she is presently living in a retirement home in Beverly Hills, California.41 [Vilma Banky Died March 18, 1991, in Los Angeles, CA]

Ronald Colman made an easy transition from the silent to the sound era, his mellow, richly modulated voice and his suave, dignified English manner making him one of filmdom's leading men. Often cast as the idealistic hero of adventure epics, he was never typecast, performing equally well in such diverse roles as the doctor in John Ford's "Arrowsmith" and the actor in George Cukor's "A Double Life," for which performance he won an Academy Award as best actor in 1947. (41)

Goldwyn had signed Gary Cooper at $50 a week for "Barbara Worth" but let him go afterwards. Paramount Pictures put him under contract almost immediately, casting him as the shy lover to actress Clara Bow. Embodying the small-town virtues of honor, simplicity, gallantry and integrity, he came to personify the strong, silent American to millions of movie-goers around the world in dozens of Westerns. (42)

With the exception of "The Virginian" (1929), with Cooper in his first starring role, and John Ford's Stagecoach (1935), the box office success of "Barbara Worth" did little to elevate the Western in the 1930s and 1940s. Script writers who might have followed up on the epic sweep and pervasive reality of the film instead resurrected and embellished the cowboy image of earlier times and transformed the Western into an assembly-line product of scant substance and even less depth.

Roy Rogers ("King of the Cowboys"), Gene Autry, John Wayne, William Boyd ("Hopalong Cassidy"), Alfred "Lash" LaRue, Randolph Scott, and even Gary Cooper himself, became stock figures in Hollywood's "Golden Age of the Cowboy," men who lived up to the "Ten Commandments of the Cowboy," but seldom worked cattle.

Productions on the scale of "Barbara Worth" did not return to the screen until the advent of such films as "The Big Country," "Ride the High Country" and "Shane" some three decades later. "Barbara Worth" was thus relegated to the archives, appreciated today only by historians, critics and film buffs. (43)

Click here to see "The Winning of Barbara Worth" as our "Feature of the Month"

ABOUT THE AUTHOR [Updated 2002]

Phillip I. Earl was curator of history at the Nevada State Historical

Society in Reno until his retirement in June of 1999. He first

went to work for the society in the 1970's and had earlier served

as the institution's curator of history.

Earl's popular "This Was Nevada" history column was

published in newspapers throughout the state for nearly a quarter

of a century.

Despite his retirement, Earl maintains an enthusiastic interest

in the history of the Silver State. He contributes information

and an occasional article to the Nevada State Department of Museums,

Library and Arts which is continuing the "This Was Nevada"

series.

The author, who continues to make his home in Reno, highly recommends

retirement saying it gives him more rest and time for physical

workouts and allows him to pick his own projects.

Born in Cedar City, Utah in 1937, Earl moved with his family at

age 4 to southern Nevada. He graduated from Boulder City High

School in 1955 and served in the U.S. Army 1957-1960. He returned

to Las Vegas area and attended Southern Nevada University (now

the University of Nevada, Las Vegas) for three years. He came

to the University of Nevada, Reno, in 1963 and received both a

bachelor's degree in history and political science and a master's

degree in history from UNR.

This is the fifth article Phil has written for the Humboldt Historian.

Prior pieces were on the early years of aviation in north central

Nevada (summer, 1979); the woman suffrage movement in the area

(winter-spring, 1981); the Seven Troughs-Mazuma flood of 1912

(spring-summer, 1982), and an account of Clara Dunham Crowell

of Lander County, Nevada's first woman sheriff.

NOTES

1. Sessions S. Wheeler, The Black

Rock Desert (Caldwell, Idaho: The Caxton Printers Ltd.,1979),

pp. 19-

34, 40-48. Gloria Griffen Cline, Exploring the Great Basin (Norman,

Oklahoma: University of Oklahoma

Press, 1963). Devere Helfrich, The Applegate Trail (Klamath Falls,

Oregon: Klamath County Historical

Society, 1971). Phillip Dodd Smith, "The Sagebrush Soldiers,

Nevada's Volunteers in the Civil War",

Nevada Historical Society Quarterly, V, Nos. 3-4 (Fall-Winter,

1962), W. 45-48. Douglas MacDonald,

"Lost Hardin Silver: Enigma of the Black Rock Desert",

Nevada Historical Society Quarterly, XI, No.1 (Spring, 1972),

w. 20-26. Francis Church Lincoln, Mining Districts and Mineral

Resources of Nevada

(Reno: Nevada Newsletter Publishing Company, 1923), pp. 103-104.

David F. Myrick, Railroads of

Nevada and Eastern California, Vol. I (Berkeley: Howell-North

Books, 1962), W. 316-333.

2. Kevin Brownlow, The War; the West and the Wilderness (New York:

Alfred C. Knopf, 1979), pp. 245- 248,368-386. Michael T. Marsden,

"The Rise of the Western Movie: From Sagebrush to Screen,"

Journal of the West, XXII, No.3 (October, 1985), W. 18-23. Arthur

Knight, The Liveliest Art: A Panoramic History of the Movies (New

York: The Macmillan Company, 1957), pp. 120-121.

3. James Robert Parish, Hollywood's Great Love Teams (New Rochelle,

N. Y.: Arlington House Publishers, 1974), W. 23-32. Los Angeles

Times, June 27, 1926.

4. Ann Lloyd and Graham Fuller, editors, The Illustrated Who's

Who of the Cinema (New York: Macmillan Publishing Company Inc.,

1983),p. 240. Los Angeles Times, June 27, July 18, October 24,

1926. Nevada State Journal, April 18, 1926.

5. Los Angeles Times, June 11, 1926. Humboldt Star, June 7, 1926.

6. Humboldt Star; June 7, 1926. Los Angeles Times, June 11, 1926.

7. Humboldt Star; June 8, June 9, 1926.

8. ibid., June 8, June 10, 1926.

9. Los Angeles Times, June 11, June 15, 1926. San Francisco Chronicle,

July 18, 1926.

10. Los Angeles Times, June 11, June 19, 1926. Humboldt Star,

June 11, June 12, June 16, 1926. Nevada State Journal, June 12,

June 19, June 23, 1926. Reno Evening Gazette, June 12, 1926.

11. Lovelock Review-Miner, June 11, June 25, 1926.

12. Humboldt Star; June 19, 1926. Nevada State Journal, June 23,

1926.

13. Los Angeles Times, June 19, 1926. Nevada State Journal, June

19, 1926. Humboldt Star, June 19, June 21, June 25, July 1, 1926.

14. Humboldt Star, June 21, 1926.

15. Nevada State Journal, June 20, 1926. Humboldt Star, June 21,

July 19,1926. Interview with Charles Reed, Lovelock, Nevada, October

24, 1964.

16. Humboldt Star, June 19, June 26, 1926. Nevada State Journal,

June 24, June 26, 1926.

17. Humboldt Star, June 23, June 25, 1926. ~

18. ibid., July 1, July 28, 1926. Nevada State Journal, June 20,

July 6, 1926. Reed interview.

19. Humboldt Star, June 11, June 21, 1926. Motion Picture Magazine,

XIV (October, 1926), quoted in Brownlow, op. cit., p. 245.

20. Humboldt Star, July 7, July 8, 1926. Reno Evening Gazette,

July 8, 1926.

21. Humboldt Star, June 26, July 9, July 17, July 20, July 28,

July 30, 1926.

22. Los Angeles Times, July 7, July 11,1926. Humboldt Star, July

12, July 13,1926. Nevada State Journal, July 14, 1926.

23. Humboldt Star, July 12, July 13, July 15, July 21, July 23,

1926. Reno Evening Gazette, July 24, 1926.

24. Los Angeles Times, July 18,1926.

25. Humboldt Star, July 15, July 19, 1926.

26. ibid., July 21, July 22, July 23, 1926.

27. ibid., July 23, 1926.

28. ibid., July 27, 1926.

29. Nevada State Journal, August 1, 1926. Humboldt Star, August

2, 1926.

30. Humboldt Star, August 6, 1926.

31. ibid., July 24, July 26, 1926. Nevada State Journal, September

14, 1926.

32. Los Angeles Times, August 14, August 20, 1926.

33. ibid., August 14, October 23, 1926. San Francisco Chronicle,

August 8, 1926.

34. Los Angeles Times, October 3, October 8, October 10, October

12, 1926.

35. ibid., October 12, October 15, October 16, 1926.

36. ibid.,October31, 1926.

37. John R. Parish and Michael R. Pins, The Great Western Pictures

(Metuchen, NJ.: The Scarecrow Press Inc., 1976), w. 407-408.

38. New York Times, November 29, December 5, 1926.

39. Humboldt Star; December 7, December 8, December 16, 1926.

40. Brownlow, op. cit., pp. 245, 248. Pierre Horay, Histoire du

Western (Paris: Editions Pierre Horay, 1964), W. 128-129.

41. Arthur Marx, Goldwyn: A Biography of the Man Behind the Myth

(New York: W.W. Norton & Company, Inc., 1976), pp. 156-157,

185-187. Lawrence J. Epstein, Samuel Goldwyn (Boston: Twayne Publishers,

1981), pp. 33-34. Barbara McNeil and Miranda C. Herbert, editors,

Performing Arts Biography, Master Index (Detroit: Gale Research

Company, 1981 ), p. 35. Information on Vilma Banky's present whereabouts

furnished to the writer by Ms. Patricia Fenton of the Screen Actor's

Guild, letter to the writer, August 21, 1985.

42. Lloyd and Fuller, op. cit., p. 91.

43. Ephraim Katz, The Film Encyclopedia (New York: Pedigree Books,

1979), p. 257. Lloyd and Fuller, op. cit., pp. 94-95. Knight,

op.cit., pp.142-188. David Dary, Cowboy Culture: A Saga of Five

Centuries (New York: Avon Books, 1982) pp. 332-338.