Silent Lives took me a while to complete -- almost forty years, in fact.

I began taking mental notes for it when I first discovered

silent films. That occurred in 1968 when I was nine years old.

Despite the turmoil of world events, it was a simple time to be

a kid in America. There were no personal computers, no home video

theaters; there was no Internet. There was television,

thankfully, and on our black and white screens it was not uncommon

to see silent movies, accompanied by cartoonish music and sound

effects. For the hobbyists there were 8mm clips of Charlie Chaplin,

Laurel and Hardy

and Felix the Cat. They were priced right, too: about $2 for a

fifty-foot reel or $7 for 200 feet. Those grainy films were my

portal to a much broader world, a world of slapstick and hilarity,

of drama and Shakespearean tragedy. Once I entered it, I never

wanted to leave.

Laurel and Hardy

and Felix the Cat. They were priced right, too: about $2 for a

fifty-foot reel or $7 for 200 feet. Those grainy films were my

portal to a much broader world, a world of slapstick and hilarity,

of drama and Shakespearean tragedy. Once I entered it, I never

wanted to leave.

To better understand the medium, I devoured every cinema history book in the public library. I also began to seek out survivors of the silent era. One was my great-uncle, Ted Edlin, who had started as a bit player in 1915. Uncle Ted spent his final years as a patient at the Motion Picture Country Hospital, an industry-supported facility in Woodland Hills, California. While visiting him there I also met and interviewed a number of retired actors and technicians. It was an invaluable education for this inquisitive film buff.

I was eager to share my newfound knowledge with everyone I met. My teachers indulged my interest by allowing me to show films during class time. The students loved it. They laughed so hard at some of the comedies that we received complaints from adjoining classrooms. Other educators heard of the slightly eccentric boy who loved old-time movies and invited me to appear as a guest lecturer, of sorts. The highlight of my early speaking career came in 1972 when I gave a presentation at Northern Arizona University. I was twelve years old at the time.

Fast-forward thirty-five years. At one time or another I have been a professional comic-impressionist, a newspaper columnist and the co-founder of a humane society; I am now a contented househusband and freelance writer. In 2001 my wonderfully understanding wife, Debra, presented me with an opportunity for which I remain truly grateful. She asked me to host a silent film series at her workplace, Willamette Oaks, an upscale retirement community in Eugene, Oregon. Perfect, I said. Here is a built-in audience of seniors, some of whom actually remember silent films when they were new. But I am at first taken aback by their pre-show questions:

I began to write brief essays,

each one detailing the facts about a particular star, and handed

them out before showing that evening's film. It worked. My regulars

now understand the empathetic nature of the Man of a Thousand

Faces. They know exactly how many times Sir Charles walked down

the aisle. They no longer repeat the myth that John Gilbert was

destroyed by talkies. They appreciate Buster's deadpan approach

to comedy. And (without being overly graphic) they can tell you

about the case of the People of California versus Roscoe Arbuckle.

I began to write brief essays,

each one detailing the facts about a particular star, and handed

them out before showing that evening's film. It worked. My regulars

now understand the empathetic nature of the Man of a Thousand

Faces. They know exactly how many times Sir Charles walked down

the aisle. They no longer repeat the myth that John Gilbert was

destroyed by talkies. They appreciate Buster's deadpan approach

to comedy. And (without being overly graphic) they can tell you

about the case of the People of California versus Roscoe Arbuckle.

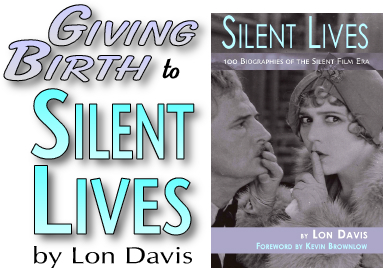

To raise money for the Willamette Oaks educational speakers' fund, I bound dozens of these essays and made them available for sale in the complex's gift shop. In truth, the information I covered is so well documented that I thought everyone already knew it. But everyone doesn't. The basics of silent films are being forgotten by the oldest Americans and have yet to be discovered by the youngest. Those in the middle -- the Baby Boomer Generation -- primarily remember silent films as the evanescent cartoons of their childhood; they have no idea just how majestic the medium can be. This realization inspired me to produce an introductory volume on the topic for a wider audience. One question loomed, however: Would anyone be interested in publishing such a book? As it turns out, yes. His name is Ben Ohmart, and he is the founder and president of a small -- but ambitious -- press in Albany, Georgia, known as BearManor Media. He read over my prototype and sent me a contract. It was that simple. Ben is a gift to the entertainment book industry.

With a publisher secured, I set about thoroughly reworking my manuscript. Once I selected the subjects, I set out to make the narratives of their lives as readable as possible. I imagined that I was crafting 100 non-fiction novellas, each limited to 1000 words. At times I focused primarily on the individual's career; in other instances, personal information is revealed. I have no desire to write a book that glosses over a subject's foibles or perpetuates unsubstantiated legends. My goal is to tell the truth. But always, I hope, with compassion and good taste.

Joining the Internet age much later than I care to admit,

I soon discovered that there are some knowledgeable silent film

enthusiasts out there -- yes, even more knowledgeable than I.

By adopting one star -- Charley Chase, for example -- these individuals

have been able to research absolutely everything there is to know

about their given subject. I sought out a variety of these specialists

and humbly asked for their input. Before long, I had a small army

of consultants:

Some of the stars unwittingly contributed to their own profiles. I referenced interviews I conducted so many years ago with Beverly Bayne, Olga Petrova, Babe London, Neil Hamilton, Mary MacLaren and Marion Mack, as well as Greta Garbo's co-star George Brent, W.C. Fields' onstage sidekick Allen Wood and Keystone Cops Eddie LeVeque and Bobby Cox. In recent years, family members have also been helpful in providing information and material. I'll always be grateful to Francis X. Bushman's widow, Iva; Harold Lloyd's granddaughter, Suzanne; Buster Keaton's son, James; John Gilbert's daughter, Leatrice; and Harry Langdon, Jr.

When I had questions of a more general nature, I turned to Anthony Slide. This prolific British-born historian has long been one of my favorite authors. His memoir, Silent Players (The University of Kentucky Press, 2002) was, in fact, the book after which I patterned my own. Another great honor has been corresponding with Kevin Brownlow, whose seminal volume The Parade's Gone By (Alfred A. Knopf, 1969) started me on my lifelong study. Kevin was endlessly patient with my questions and requests. He even provided Silent Lives with its insightful foreword.

Photographs, I feel, are of great importance to a film book-it is a visual medium, after all. This brings me to Cole Johnson, David B. Pearson and Tim Lussier. These guys are as generous as their collections. Many of the nearly 200 images they provided have not been seen in decades. Some have never been seen at all.

Of course, this

is a book about moving pictures. With that in mind, I received

Ben's approval to produce an 80-minute DVD that will be included

with every copy of the book that is purchased through BearManor

Media's Web site. The majority of the twenty-one clips that make

up Classic Screen Moments are courtesy of A-1 Video, Alex

Bartosh's online mail-order company. The authentic musical accompaniment

was made possible by recordings provided by Hugh Munro Neely of

Timeline Films in Los Angeles and Jose Gonzales of Timeless Media

Group in Eugene. All of the material was put together by an imaginative

young editor named Glenn Hanna. Glenn suggested I record a commentary

as a bonus feature, which I was happy to do.

Of course, this

is a book about moving pictures. With that in mind, I received

Ben's approval to produce an 80-minute DVD that will be included

with every copy of the book that is purchased through BearManor

Media's Web site. The majority of the twenty-one clips that make

up Classic Screen Moments are courtesy of A-1 Video, Alex

Bartosh's online mail-order company. The authentic musical accompaniment

was made possible by recordings provided by Hugh Munro Neely of

Timeline Films in Los Angeles and Jose Gonzales of Timeless Media

Group in Eugene. All of the material was put together by an imaginative

young editor named Glenn Hanna. Glenn suggested I record a commentary

as a bonus feature, which I was happy to do.

After watching Chaplin, Keaton, Lloyd and the best of Griffith,

the viewer will no doubt be looking up the film distributors'

Web sites that I list in Silent Lives' appendix. I also

include addresses for dozens of related study sites and -- for

the researchers of the future -- hundreds of bibliographical sources.

With immense pride, I'd like to quote some of my favorite authors

:

copyright 2007 by Lon Davis; all rights

reserved

Back

to "Articles and Essays" page