With The Vagabond (1916), Charlie Chaplin proved

that characters in a comedy could move an audience as compellingly

as characters in a drama. Depth of feeling, foreign to slapstick

comedy generally, was rare even in Chaplin's early work. Chaplin's

artistry grew as his control over production increased, and from

the Keystone days through his best work at Essanay we see him

steadily refining and polishing -- gags and business, of course,

but especially the iconic figure he had brought into being in

1914. By the time of the Mutual films this figure was less the

Tramp than "the little fellow," occupying whatever role

the present story required (fireman, wealthy toff, pawnshop employee,

policeman) but remaining the same person from film to film, a

romantic outsider, much-buffeted yet ever resilient, ever hopeful.

The Vagabond was the third film to be released under Chaplin's

Mutual contract, but it feels like the first. This is due to its

extraordinary beginning: two floppy, splayed shoes, topped by

baggy pants, shuffle toward the camera from beneath the double

doors of a saloon. Throughout the world reached by moving pictures

in 1916, no habitual moviegoer would have been in the least doubt,

during these fleeting seconds, as to the owner of the bunched

trousers and oversized shoes. Instant recognition was no mere

byproduct of celebrity but the stunning proof of Chaplin's global

reach, of fame raised to a power unmatched by any artist in any

medium at any previous time in history.

By 1916 Chaplin's little fellow had become his own logo. The next

moments of The Vagabond acknowledge this. The saloon doors

part and the little fellow emerges, clutching his violin, to stand

before us in the center of the screen. We see him tip to toe,

full figure, his derby barely clearing the top of the frame, his

shoes nearly touching the bottom. It is a singular moment in  the Mutuals, perhaps in all of

Chaplin. Whether projected onto a state-of-the-art Mirroroide

screen or a white plaster wall, Chaplin's image would have loomed

large, filling the vertical space more imposingly than the soon-to-be-familiar

Goldwyn Pictures lion, the Pathé News rooster, or the Paramount

peak. The pose, held for several seconds, is a mute proclamation,

rendering title cards superfluous. It says, You know who I am

whether you can read or not. But if you can read, then yes, I

am the fellow your newspaper describes as the highest paid entertainer

in the world. And I am here once again to show you why.

the Mutuals, perhaps in all of

Chaplin. Whether projected onto a state-of-the-art Mirroroide

screen or a white plaster wall, Chaplin's image would have loomed

large, filling the vertical space more imposingly than the soon-to-be-familiar

Goldwyn Pictures lion, the Pathé News rooster, or the Paramount

peak. The pose, held for several seconds, is a mute proclamation,

rendering title cards superfluous. It says, You know who I am

whether you can read or not. But if you can read, then yes, I

am the fellow your newspaper describes as the highest paid entertainer

in the world. And I am here once again to show you why.

Many in the audience would already have gasped at reports of the

$670,000 salary guaranteed to Chaplin for furnishing twelve short

comedies, one per month, to the Mutual Film Corporation. His first

effort under the new contract, The Floorwalker, boasted

an elaborate department store set, complete with a moving staircase.

Unlike the typical Keystone or Essanay short, the comedy was expensively

produced and looked it. Yet neither The Floorwalker nor

its follow-up, The Fireman, had the touch of pathos that

had so distinguished The Tramp, released by Essanay barely

a year earlier. The Vagabond reintroduces sentiment to

Chaplin's comedies. From here on, in many of the shorts and in

all of the silent features, the little fellow will face situations

in which something of vital importance -- life, love, liberty

-- stands to be lost.

In outline, The Vagabond is the stuff of melodrama. A young

woman, forced to work as a drudge for a band of abusive gypsies,

is revealed to be the kidnapped daughter of a wealthy society

woman. An itinerant violinist, decent but penniless, ignorant

of the young woman's past, comes to her rescue -- and falls in

love with her. But he must stand by, helpless to assert his love,

as she is identified (by a birthmark) and restored to her wealthy

family.

Kidnappings by gypsies, Peter Kobel reminds us, figured in silent

films as early as Cecil Hepworth's Rescued By Rover (1905).

They were central to the plot of both D. W. Griffith's The

Adventures of Dollie (1908) and Edison Studios' The Girl

of the Gypsy Camp (1915). Chaplin thus chose to build his

third comedy for Mutual on a conventional, even overfamiliar,

storyline. The laughs in The Floorwalker and The Fireman

were more or less bounced off the setting, but in The Vagabond

they emerge from the little fellow's sudden entanglement in an

ongoing and potentially tragic series of events.

Chaplin brings this off not only with a nod to theatrical tradition

(that fount of melodrama) but with a cinematic intelligence rarely

attributed to him. Historians are right to point out that Chaplin

liked to park his camera and spend his time instructing each of

his actors what to do in front of it. But it's a mistake to assume

that his respect for the proscenium made him any less dedicated

to the exciting possibilities of cinema. His camera does move,

but seldom without a good reason. He is as alive to what is inside

the frame as to the ways in which individual shots can be manipulated.

In The Vagabond we see his increasing sensitivity to proportion,

contrast, and the telling arrangement of objects and people. He

establishes the characters of the violinist, the society woman,

and the kidnapped daughter with a deft visual shorthand that --

in a two-reel comedy from 1916 -- is nothing short of astonishing.

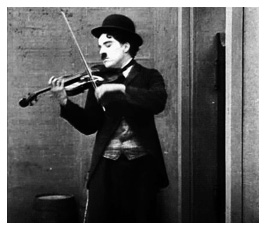

We know more about the "Street Musician"-- Chaplin's

stated role -- in the first minute of the film than any title

card could have told us. The little fellow leaves the swinging

doors of the saloon and walks away from us along the side of the

building. The camera stubbornly refuses to move, so that the retreating

figure is confined to a narrow column of space at the extreme

left of the screen, while three-quarters of the screen, depicting

the front of the saloon, remains unoccupied. After some brief

comic business, the camera resumes this vantage point -- and all

at once we understand why. A robust German band, five big men,

show up and begin to play in front of the swinging doors. The

violinist, meanwhile, saws away outside the tavern's "Family

Entrance" at the far end of the narrow corridor, his figure

shrunk by distance to a fraction of the size of the foreground

figures. The shot is deep focus before deep focus had a name,

and it reveals in an instant the social status of Chaplin's little

fellow. Literally reduced, literally marginalized, he is shown

to be alone, scuffling for work, and keeping -- or being kept

-- to the periphery.

We understand the world of the society woman by first understanding

what it isn't. From the rough-and-tumble of the saloon, we jump

to a richly appointed drawing room. We might have stumbled into

one of Cecil B. DeMille's domestic dramas of the 1920s, but not

even DeMille's upper-class interiors were this ornate. There are

Persian rugs, paintings, upholstered furnishings, glassed cabinets,

candelabra and wall sconces, vases of fresh flowers, even a massive

crystal chandelier, all of it redolent of European refinement

-- of wealth, elegance, stately reserve. It could not be more

different from the grimy saloon. Yet the opening shot of the room,

as the camera begins a slow pan, is explicitly modeled on the

opening shot of the saloon. The tavern's swinging doors are echoed

here in the draped doorway that reveals, beyond the opulent drawing

room, a second room containing heavier furniture, a fireplace,

and a large painting. On both sides of the doorway hang small

oval portraits that recall the two oval signs ("Cool Beer")

flanking the double doors of the saloon.

Chaplin aligns the two doorways, and the very different worlds

they represent, without lingering over the comparison. He doesn't

need to. The scene introducing "The Mother" takes up

a mere 37 seconds of screen time, yet it convinces us of the crushing

emptiness of her life. After watching a dozen men brawl in a saloon,

we find ourselves in sedate rooms devoid of people, or nearly

so. The camera drags our gaze from a vacant loveseat, bench, and

chair, past the gaping doorway, to a table where the mother sews,

clearly alone with her thoughts, beside an older female companion.

When the mother finds a small framed portrait -- the picture of

a young girl -- in her sewing basket, she is visibly grief-stricken.

We are already prepared to say why. Surrounded by sumptuous possessions,

the mother has been denied the only possession that really matters:

her own daughter.

The portrait of the little girl provides a poignant link to the

scene introducing her older self. As the mother's companion leans

over the table to pick up the portrait, the words "The Gypsy

Drudge" appear on a title card. We iris out on the face of

Edna Purviance, looking distressed and haggard, her cheeks mottled

with dirt and her hair in a tangle. But as it frames her anguished

features, the iris pauses. For nearly three seconds, Edna's sad,

haunting face, like a picture squeezed into a locket, is all we

can see on the darkened screen. Then the iris opens out and we

are confronted with the squalid reality of her life in the gypsy

camp. It's a heart-rending moment, beautifully realized in the

camera.

Into this world the little fellow wanders, and the fun resumes.

Here, as in the feature comedies to come, gags are played off

the mood of the moment, and the mood is determined by what is

at stake in the scene.

Despite his characteristic sympathy for the underdog, Chaplin

wastes no affection on the peasant gypsies and gives them little

in the way of comic business. They are almost to a man (and woman)

shown to be oafish brutes who deserve the punishment the little

fellow doles out (clonking them on the noggin with a hefty stick).

As the "Gypsy Chieftain," Eric Campbell gets at least

one good laugh when he leads the chase to recapture the fleeing

caravan. After Edna clonks him, he collapses in the road and is

dutifully tripped over by every single gypsy -- seven in all --

running behind him. Despite the buffoonery, Campbell is for the

most part a scary presence in the film, scarier than the vicious

ruffian he would portray in Easy Street.

Few characters in Chaplin's films are immune to satire, and some

of The Vagabond's funniest moments are at Edna's

expense. Her standards of hygiene, after years of living rough,

offend even the dusty Charlie. When she joins him outside the

caravan the morning after their escape, she is a slovenly sight

to behold. Her clothes are ragged and disordered, her face is

filthy, her hair sticks out in clumps. Charlie stares at her as

she scratches her scalp and helpfully hands her a garden rake.

When she shows no interest in his proffered bar of soap, preferring

to complete her morning toilet by dabbing a wet finger beneath

each eye, he finally takes matters in hand and sits her in front

of a bucket of water.

Edna's wash-up, during which Charlie scrubs her face, ears, and

nostrils with a soapy sock and meticulously dries them with a

flannel shirt, may be the tenderest scene in all of Chaplin's

short comedies. Purviance, a placidly beautiful woman, had never

looked so bedraggled on film, and we can imagine audiences of

1916 taking delight in the transformation. Edna endures the scrubbing

much as a child would, squinting and blowing against the suds

-- but not protesting. Charlie's attentions, as automatic as they

are intimate, express the loving parental care she has been denied

since her kidnapping.

Chaplin's most pointed jabs are reserved for the leisured classes.

Even the little fellow's highbrow airs are ridiculed. Brandishing

his violin, he first plays so violently that he tumbles backwards

into a water barrel and sends Edna crashing over her washtub.

His performance concludes with a flurry of pretentious curtain

calls -- a hilarious bit which, thanks to Chaplin's superb mimicry,

combines the virtuoso's humility in the face of applause with

the vanity that keeps him coming back for more. The sequence ends,

as it must, with another pratfall into the water barrel.

He takes a more penetrating look at the real upper class. While

the painter who discovers Edna in the woods is charming and affable,

he is also something of an aesthete with time on his hands. He

is inspired to paint Edna as "The Living Shamrock,"

but he gives no indication that he means to rescue her from the

wretched conditions of her existence -- or even to pay her a return

visit. Only the wealthy mother's chance sighting of his finished

painting (depicting a vivacious, idealized Edna, with no hint

of the gypsy drudge) leads him to retrace his steps. The first

thing Charlie does upon seeing the painter again (now attired

in top hat and tails) is to drop a handful of eggs on his shoes.

We may laugh at the painter -- Charlie ends by shaking his hand

-- but we are not encouraged to laugh at the mother. Or admire

her, it turns out. At last reunited with her daughter, she can

barely conceal her disdain for Edna's true savior, the vagabond

in ill-fitting clothes. Drawing Edna to her, she extends some

folded bills which the little fellow, with a wise, dismissive

gaze, brushes aside.

Chaplin's unsparing portrayal of the mother sets the stage for

the film's conclusion. All but swept off her feet, Edna rides

away in a cloud of dust with her mother, the painter, their well-dressed

friends, a footman, and a chauffeur. Then, suddenly realizing

who it is she really loves, she forces the car to turn around

-- and invites the little fellow along. The ending -- her return,

his going off with her -- has been criticized as being unlikely

or unrealistic. Lack of realism is a peculiar charge to bring

against any Chaplin comedy, but it is particularly misleading

with regard to The Vagabond. Far from seeming improbable

or gratuitous, the film's final scenes carry a genuine emotional

wallop. Edna's "awakening" in the back seat of the car

-- her growing unease, her looking back, her impassioned cry --

is utterly convincing, flooding the screen with emotion without

the use of a single dialogue title. Chaplin has made sure we can

read every word on her lips:

We watch from the camp as the car speeds away again, carrying

Edna and Charlie toward a future impossible to foresee. Thanks

to Chaplin's subtle magic, our hearts go with them.

Copyright 2014 by Mark Pruett. All rights reserved.