The music we hear in films, television shows, commercials, and in video games serves many purposes: it can give us background information about the story (if there is one); it can set up things historically (through the use of period-specific instruments or songs) or geographically (with the help of instruments or melodies associated with particular places, like a sitar for India or a Hardanger fiddle for Norway); it can provide a window into a character's soul, belying if the person onscreen is good or evil; it can foreshadow events to come, including if the killer is waiting in the next room, just off-screen. All of these tasks-and more-routinely fall to the music. Nowadays, music for soundtracks is big business: songs and artists alike can become household names worldwide through a single appearance in a hit film or a popular television series (say, The Sopranos or Grey's Anatomy). In the early 1900s, however, when the film industry was first getting going-and the period from which this music hails-no composer was famous solely for having written for films.

Film music was thus a burgeoning area for composers in the early 20th century. Since no one had yet invented a successful way to synchronize sound recordings and film, movie houses and music publishers devised other methods to make music available. These methods included detailed lists of pieces (or cues) to use for each scene in a film; such lists are called cue sheets, and today these lists provide us a great deal of insight to the music that might have been used when a film was shown. (I say might because theatre musicians were under no obligation to use the music suggested in cue sheets -- they were just that, suggestions.) Some film companies occasionally had original musical scores commissioned for a single film. The process was so time-consuming and expensive, however, that typically only high-profile films received such treatment, such as D.W. Griffith's The Birth of a Nation (1915).

An exceedingly more economical (in work and money) source of music could be found in photoplay music: generalized, stereotypical mood music written expressly to be used with films. Similar melodies had long been used in melodramatic stage dramas, in which original music and well-known works of 18th and 19th century music was used to craft the soundscape of a production. Every genre and type of music imaginable shows up as photoplay music: music for sad events, happy days, suspense, joy, as well as music for different ethnicities (China, Japan, African Americans, Indians), nationalities, and everything in between. The music was printed either with clearly suggestive titles (such as "Battle Music," "Waterfall," or "Treacherous Knave" in this collection) or just with suggestions as to possible scenes in which it might be used.

While several major music publishers in the United States produced collections of photoplay music, only one composer really made this type of music his specialty. John Stepan Zamecnik was born into a musical family Cleveland, Ohio on May 14, 1872: his father and at least one uncle were also known locally as musicians (as bandleaders in civic and militia groups). Early notices of Zamecnik performing in public begin as far back as 1887, where he is listed in the Cleveland Plain Dealer as taking part in a quarterly concert at the Cleveland School of Music (which ran from 1875-1938), and again in 1888, when he was part of the band (which also included several other Zamecniks) that accompanied Battery A of the First Regiment of the Ohio light artillery on a journey from Cleveland to Columbus. Zamecnik also began making a name for himself as a violinist playing in a local quartet led by composer and conductor Johann Beck.

In the mid-1890s Zamecnik left Cleveland to pursue studies in composition (and organ!) at the Prague Conservatory, which boasted none other than Antonin Dvorak as the head of composition (and later director of the school) and classmates including Jan Kubelik, later to become world-famous as a violinist. When Zamecnik returned to Cleveland, he also returned to his career as a performer, dividing his time between his hometown, where he played in various local ensembles, and traveling to Pittsburgh (a distance of more than 130 miles) to play second violin in the Pittsburgh Symphony under the direction of Victor Herbert. At the same time he began making a name for himself as a composer; the Cleveland Symphony Orchestra, a short-lived (1900-1901, 1902-1913) ensemble, performed Zamecnik's "Slavonic Fancies" on its second concert ever, February 20, 1900, conducted by Johann Beck. By 1903 his local fame had risen to the point that a lengthy Plain Dealer article titled "Cleveland is Taking Her Place Among Musical Cities" named Zamecnik as one of three prominent or rising orchestral composers in the city.

By 1907 Zamecnik's output reached a new plateau, as he began two new major endeavors. The first began in the spring of 1907, when Zamecnik provided music for a musical revue, The Hermits in California, put on by Cleveland's Hermits Club, a fraternal organization of amateur and semi-professional performers in the arts. Zamecnik joined the Club and ended up writing music for five revues, following the Hermits in their exploits around the world, from the American South to Paris and even Africa. While playing around town at various venues during 1907, including a long-running engagement at the Lyric Theatre in downtown Cleveland, Zamecnik also became the first musical director at the new Hippodrome Theatre, a palace of a performance space that seated 4500, showcased live animals (including elephants) on stage, and boasted a massive water tank (reportedly holding in excess of 150,000 gallons of water) to allow for "aquatic spectacles" during the various shows, including a diving horse act. Zamecnik wrote music for several shows staged at the Hippodrome, including two for the opening, Coaching Days and Cloud Burst. It was around this same time that Zamecnik first began working with publisher Sam Fox; his first song published by Sam Fox was "College Yell" (1908), followed eventually by hundreds of others. Zamecnik not only wrote instrumental marches and dances, he also provided music for dozens upon dozens of songs, collaborating with several lyricists (including two songs for Coaching Days).

The other key person in our story is the man who made a priority of publishing instrumental music at a time when the big money -- so it seemed -- was in pop song publishing. Also born in Cleveland, Sam Fox grew up playing in local orchestras, including leading the orchestra at Central High School, where he was a student. While still a teenager, he began writing and self-publishing his own songs, a clear indication of where he felt his strengths lay as a professional. By the turn of the century he'd gone to work for a local instrument maker and publisher, H.N. White, but apparently struck out on his own quickly, and by 1906 had established Sam Fox Publishing, with an office at the fashionable and centrally located Arcade building in downtown Cleveland. By 1919 he was hailed with the following praise: "Probably none of the younger generation of music publishers is rated as being more successful than Sam Fox."

Not long after Zamecnik began working for Sam Fox we begin to see the earliest published collections of music targeted at film accompanists, beginning in 1909 with Motion Picture Piano Music, collected, arranged, and published by Gregg Frelinger in Lafayette, Indiana. This and other anthologies released over the next several years were essentially collections of recognizable melodies drawing from classical music, folk tunes, and national airs, all of which could be used in films for any of the purposes described earlier. Publishers very quickly and cannily took dramatic and atmospheric music they already owned and began reprinting it and marketing it toward theater musicians. Other publishers, including Sam Fox, simply commissioned new mood music (or photoplay music, as some called it) for use in films.

Between their first published collections in 1913 -- Sam Fox Moving Picture Music, volumes 1 and 2-and 1929, Sam Fox published hundreds of pieces (and collections of pieces) of photoplay music, and J.S. Zamecnik wrote practically all of them (and, for good measure, arranged those that he didn't write). All but two pieces in this collection come from the four volumes of Sam Fox Moving Picture Music published between 1913 and 1924, and represent the gamut of moods and themes that one might expect in a dramatic potboiler. In many cases, these volumes took songs that Zamecnik had already written and released solely for piano and republished them in orchestrated form. To give a sense of how widely Sam Fox published in film music, the company also released five volumes of the Sam Fox Photoplay Edition (each consisting of a dozen different pieces), a Motion Picture Themes Series collection, a Theatre Pianists and Organists Series, a News Reel Folio series, a Paramount Edition series (connected with Paramount Studios), as well as several series of band, orchestra, concert orchestra, and other ensemble designations that could be easily adapted to theatre use. Finally, Sam Fox made a deal to publish the theme songs for films produced by Paramount, several of which had music written by Zamecnik, including the winner of the first Academy Award for Best Picture, Wings (1927).

As a distinct genre, photoplay music ceased to exist at the end of the 1920s: when The Jazz Singer was released and studios began slowly but surely moving toward using synchronized sound, music directors and composers began creating original scores for films, knowing that the music could and would be faithfully reproduced in theatres (along with the voices and sound effects that an included soundtrack would allow). Mood music didn't disappear, of course: especially in the early days of sound film, the same music for bullies, heroes, thunderstorms and attacking foes showed up in the soundtracks, and in many cases, it was the exact same photoplay music that had been used in the pre-sound days. Zamecnik's music in particular seemed so versatile that it lasted long into the latter part of the 20th century, being used for live action films and especially animated cartoons, where his descriptive melodies underscored hundreds of cartoons released by Warner Bros. and other animation studios. Through recordings like the Erie Chamber Orchestra's The Sounds of the Silents and the ongoing revival of interest in cartoons and films from the first half of the 20th century, Zamecnik's music of diverse moods will always be audible to audiences.

copyright 2014 by Daniel Goldmark. All rights reserved.

|

Daniel Goldmark is Associate Professor, Music, Case Western Reserve University. He is also Editor of Sounds for the Silents: Photoplay Music from the Days of Early Cinema (Dover Publications, 2013). |

"The Sounds of the Silents" press release:

Is Cleveland the birthplace of the music you hear marching,

crashing and whispering along behind the mayhem and spectacle

of your children's computer games or the latest Hollywood  blockbuster? It's a question that might

be answered by "Sounds of the Silents," the new recording

of music by Cleveland-born John Stepan Zamecnik by members of

the Erie Chamber Orchestra.

blockbuster? It's a question that might

be answered by "Sounds of the Silents," the new recording

of music by Cleveland-born John Stepan Zamecnik by members of

the Erie Chamber Orchestra.

If Zamecnik's name is not familiar to you, it's not very familiar to many musicians and scholars, either. Still, 100 years ago, his music might have been as ubiquitous as that of any composer in America.

At a time when dramatic music was played live by theater orchestras, Zamecnik had a gold-plated gig as music director of Cleveland's Hippodrome, which boasted more than 4,500 seats and the world's second-largest stage. To fill it, Zamecnik wrote big music: rousing marches, chatty character pieces and weeping melodies that caught the interest of the nascent motion picture industry. Zamecnik cranked out hundreds of these pieces for Hollywood and became one of America's most successful composers of so-called "photoplay music."

And ironically, he is one of the most anonymous. Case Western Reserve University Zamecnik scholar Daniel Goldmark identifies most of the music for "Wings," the winner of the first "Best Picture" Oscar in 1927, as Zamecnik's, though he was not credited. When talking pictures changed the function and the centrality of movie music, Zamecnik was quickly forgotten.

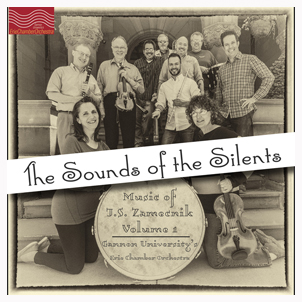

Orchestra executive director Steve Weiser discovered complete parts for Zamecnik's music in the collection of the orchestra's founder Bruce Morton Wright. It was the largest collection of the composer's work to have come to light.

The ECO played a few of the pieces at various short concerts, and then, as Weiser said, "The more we played the music, the more we knew we needed to record it because audience loved it -- and that there were no recordings of it. We had 14 pieces that had never been recorded before."

Recording sessions were held in Gannon University's Yehl Room over Memorial Day weekend 2014 engineered by Gannon's own Sam Hyman. "We did a seven tracks the first day, seven the next. Music director Matt Kraemer conducted and it was a blast," Weiser said.

"Sounds of the Silents" is available on iTunes, Amazon and the Erie Chamber Orchestra webpage at http://eriechamberorchestrablogs.com/soundsofthesilents/ where you can also listen to track previews.