One wonders what must have flitted through the minds of Hollywood's first generation of great names when their contemporaries Wallace Reid, Barbara LaMarr, and Rudolph Valentino died shockingly young in the 1920s. Surely they must have wondered, as we all do, just how long the Fates would draw out their own thread of life before snipping it off; perhaps they wondered where, and with whom, they themselves one day would lie.

Whatever their thoughts may have been, we who now study the closed circle of their lives and their roles in the early days of American film can note, with a touch of comfort, how many of these great names now rest with family. At Forest Lawn Cemetery in Los Angeles, Mary Pickford is entombed with her mother, sister and brother; not far away lies her second husband, Douglas Fairbanks Sr., joined some 60 years after his death by his son and namesake. At Saint Bartholomew's Church in New York City, Lillian Gish rests with her mother and sister; and in Vevey, Switzerland, Charlie Chaplin lies with his wife, Oona. All, we might note, are buried far, very far, from their places of birth.

I mention these names not only because they

are among filmdom's royalty, but because their lives touched that

of the Father of American Film: D. W. Griffith. And Griffith's

burial place? Not in Hollywood or in New York City, where he made

his most famous films, and certainly not in the Swiss Alps. No,

to find Griffith's grave, you must go to a rural area of Kentucky

not far from Louisville. Only when you arrive at Mount Tabor Methodist

Church,  near the little village of Crestwood, will you notice

a plaque by the road, the sole indicator that this serene area

was home to the most legendary of America's film pioneers

near the little village of Crestwood, will you notice

a plaque by the road, the sole indicator that this serene area

was home to the most legendary of America's film pioneers

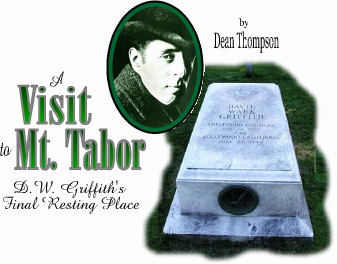

Mount Tabor is where Griffith worshiped as a boy, its cemetery the resting place of his parents and siblings; after fame and wealth had come his way, Griffith commemorated his father and mother's lives with an enormous monument that even today dwarfs all the other cemetery markers (see photo at the bottom of this page).

Griffith himself is buried 75 feet away, his the only grave surrounded by a split-rail fence, said to have been taken from wood on the Griffith Farm. A full-length stone marker, placed by the Screen Directors' Guild in 1950 and adorned with its crest, covers the grave. The laying of this marker, by the way, was attended by Lillian Gish, Mary Pickford, and Richard Barthelmess, all of whom began their careers with Griffith. Also present was Evelyn Baldwin (Griffith's ex-wife). (see photo at the bottom of this page)

Standing in the shade here and feeling the soft breeze, one remembers that the last few miles leading to this quiet ground are dotted with old barns and silos amidst the rolling pastureland and streams that Griffith himself must have gazed upon, not only in his youth, but during his frequent sojourns to Crestwood in the 1930s and 1940s, long after his career had ended. One remembers, too, a particularly moving passage from Richard Schickel's D. W. Griffith: An American Life, the definitive biography. Shortly before his death in 1948, Griffith granted one last interview that took -- how could it not? -- a nostalgic turn. Schickel comments that

"(Griffith) missed

a certain beauty he thought had disappeared from film, from the

way people saw life -- 'the beauty of the moving wind in the trees,

the little movement in a beautiful blowing on the blossoms in

the trees. That they have forgotten entirely. . . We have lost

beauty.' On that note, Griffith fell silent. On that note, if

one were directing the scene, one would begin a slow pullback.

Whatever had become of him, whatever had become (or would become)

of the medium that he had been the first to conceive of as an

art, that fragile essence of his sensibility, at its best, and

of one of cinema's potentials at its  most generous, he had now fleetingly

evoked one last time. . . .

most generous, he had now fleetingly

evoked one last time. . . .

"The problem was not merely that pictures now talked. Or that they had become big business. Or that a new age of anxiety was upon the movies as television . . . destroyed everyone's confidence. No, it was more than that. It was, really, that everyone had now arrived where Griffith had arrived perhaps two decades earlier -- at a place where innocence was lost, and with it the capacity to wonder at the miracle of a medium that could, if it would, show us, in the flicker of a ten-frame cut, something of our inward life, or, if you will, find in the trembling of a leaf, the symbol of an unknown yearning, an unspoken dream. In all the long years of wandering and confusion, in all the long years when his own peculiar demons drove him down strange paths, in all the long years when, being the product of his bustling times and this often vulgar place, he had lost touch with his best self, his best and simplest hopes for this thing he had made. But now, at the end, he remembered." (Schickel, p. 603)

Schickel's appraisal of this final summing up (Griffith's "dying fall," he terms it) makes one see afresh not only the rightness of this burial spot, but also the way that Griffith's work may best endear itself to future generations. His reputation is a diminished thing in these days of political correctness, for the unfortunate portrayals of African-Americans in his films, "The Birth of a Nation," in particular, have clouded his name. If film students and aficionados learn their Griffith at all today, they are most likely to see the clips most associated with him: the awe-inspiring crane shot of Belshazzar's Feast from "Intolerance" or the last-minute rescue of Lillian Gish on the ice floes from "Way Down East."

But even these clips, I think, are muted,

at least when shorn of the carefully structured framework of Griffith's

best films: one might as well  show students of

architecture a portal without stepping back to view the entire

building. And we now see spectacle and hair-raising rescues all

the time.

show students of

architecture a portal without stepping back to view the entire

building. And we now see spectacle and hair-raising rescues all

the time.

No, if Griffith is to be experienced with immediacy and without apologia (for both the world and we who sit before the screen have changed beyond measure in the century since Griffith's earliest work for Biograph), we must return not to the overfamiliar clips, not to the racial attitudinizing that pins Griffith to his time and place, but to the simple sequences that must have seemed throwaways to earlier generations of filmgoers for whom the pastoral was an understood form of art, for whom a closeness to the land and to family was more often a given than it is today. Consider, and revisit, these central moments in Griffith:

-- Elsie Stoneman and The Little Colonel's shy kiss after stroking a dove in "The Birth of a Nation."

-- The lovely pan shot of field, river, and trees that opens "A Romance of Happy Valley."

-- David Bartlett's proposal to Anna Moore in the midst of a field of sunflowers in "Way Down East"; or the single shot of a kitten falling asleep between a little boy's legs as he dozes on the front porch of a general store; or Anna's tending to David's parents as they rest by their well; or the sleigh ride; or David's waltzing his mother around their living room.

-- Lucy Butler's wistful, heartbreaking gaze at the geranium she will never be able to afford in "Broken Blossoms."

-- A poor German family's joy when their hen starts laying in "Isn't Life Wonderful?", or their touching thankfulness when they dine on potatoes.

-- The extended shots of a farmer sowing his fields in "A Corner in Wheat."

There are scores of these miniatures across the canvas of Griffith's work, and doubtless you have your own favorites. And of course there is so much more to Griffith than individual sequences or shots. But one quickly comes to notice how Griffith lingers on these miniatures, rather in the way we might linger over a favorite photograph or keepsake from the past; the image before us suddenly takes on a warmth and humanity as fresh as the day it was caught on film. To put the point another way: in viewing Griffith's work from the early Biographs to the romances and great symphonies of the 1910's and 1920's, one marvels at his skill in marshaling his resources to create (as Orson Welles termed it) the very language of motion pictures. But in these quiet, glowing moments, one senses Griffith's love; and here the medium of film takes on its greatest power -- not to excite, not to hold in suspense, but to speak with directness to the heart. Few directors have understood this power as well as the Kentuckian who discovered it.

How appropriate, then, that Griffith rests far from the industry, and even the West Coast city, that he helped create; how fitting that he is surrounded by farmland, shady trees nudged by the wind, and rolling streams, to which iconic images he aimed Billy Bitzer's camera with the surety of a master painter laying his brush on canvas. In his films, in his life and death, he knew where to return.

article copyright 2002 by Dean Thompson. All rights reserved.

|

|