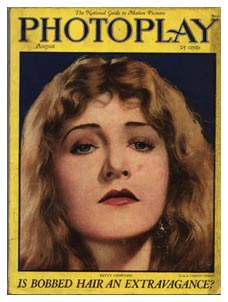

I "discovered" Betty Compson at the 1998 Cinevent when I saw her first in "Paths to Paradise" with Raymond Griffith and then in "Docks of New York" with George Bancroft. Although the two films required completely different performances, I was totally "blown away" by this lovely actress who could hold her own with a comic genius such as Griffith or melt your heart in a melodrama as a poor waif who has no reason to live.

As Molly, a jewel thief, in "Paths to Paradise," the winsome Miss Compson was perfectly teamed with Griffith who played a rival jewel thief. As the two competed with one another to steal a necklace in a home where Compson posed as a maid and Griffith posed as a wealthy bon vivant, the screen literally lit up with personality, wit and charm. Although Griffith is a top rank comedian, he wasn't able to overshadow Compson's performance. She switched from a demure, obedient maid to a tough, determined burglar convincingly and adeptly while retaining her charming beauty through it all.

Of course, the much better performance, and maybe the apex of her career, is in "The Docks of New York." She is Mae, a destitute girl who tries to commit suicide but is saved by a rough coal stoker named Bill who just pulled in on a ship. Compson tugs at the viewer's heartstrings and draws forth a wave of sympathy for the poor, hopeless Mae who has been beaten down by the Fates. The viewer wants to rescue her from her misery, especially when it appears that Bill is going to leave her and go back to the ship the next morning after they were married. At this point in the film, Compson has the viewer empathizing with her plight so much that you are almost "rooting" for Bill to come back to her.

Silent film historian Kevin Brownlow called "The Docks of New York" "one of the enduring masterpieces of the American cinema." He said Betty Compson's portrayal of Sadie was "electric," and, certainly, it was and still is.

While attending high school in Salt Lake City, Compson played

violin in the Mission Theatre orchestra which accompanied the

movies and the vaudeville acts appearing there. She was such a

success, she teamed up with three young men and, accompanied by her mother, went to San Francisco

to get bookings. No bookings were secured, however, and the three

young men left the act. Compson did manage to get a 15-week tour

as a solo violinist act.

young men and, accompanied by her mother, went to San Francisco

to get bookings. No bookings were secured, however, and the three

young men left the act. Compson did manage to get a 15-week tour

as a solo violinist act.

Back in Salt Lake City, she began touring with a couple of Pantages shows doing her violin specialty. When the show played in Los Angeles, she made a film test for Christie. She finished the tour and got a call from Christie in Salt Lake City offering her a contract.

Actually, Compson's given name was Eleanor Lucime Compson. It was Christie who christened her "Betty." She was a success in the comedies, and, in 1916, "Motion Picture News" said, "Betty Compson grows more fascinating with each succeeding picture."

In John Kobal's book, "Hollywood, The Years of Innocence" (Abbeville Press, 1985) there are two nude photos of an actress taken by the Evans Studio in 1916. According to Kobal, the actress is identified on the slides as Betty Compson, who would have then been 19 years old. Kobal feels "the attribution is open to question," but adds, "if it is Betty Compson, she wouldn't have been the first actress - or the last - to have begun her career by posing in the nude."

After making over 70 comedies for Christie, she was fired in 1918 because she refused to make a personal appearance. Compson was almost destitute when she landed a role in the Pathe serial "The Terror of the Range." It was during this time that she began to make a lot of contacts with the up and coming stars of the day such as Rudolph Valentino, Bebe Daniels, Gloria Swanson, John Gilbert and others. It was also at this time that she met James Cruze for the first time, her future husband.

On Dec. 23, 1918, she got a call after work one day from director George Loane Tucker. He wanted to talk to her about a new picture he was going to make. After meeting with her, Tucker offered her the role of Rose in "The Miracle Man" for $125 a week. The success of "The Miracle Man" made stars of her, Lon Chaney, Thomas Meighan, and Elinor Fair.

Tucker directed her in "Ladies Must Love," as well, and, by this time, Compson had fallen in love with the director, but he was married and soon found out he was dying of cancer. As a last favor to her, he negotiated a new contract for Compson with Paramount, and died shortly after. Compson was devastated.

Tucker had wrangled an amazing $2,500 a week for Compson, and she was one of Paramount's brightest stars for the next two years. However, due to poor direction, her pictures were not successful enough for Paramount to offer her a raise, and she refused to sign without one.

From 1922-1924, Compson made films in England, quite successfully. She got homesick, however, and returned to Hollywood signing with an independent producer for $3,500 a week. In the meantime, one of her English films, "Woman to Woman," was released in the United States and was a hit. Jesse Lasky asked her to come back to Paramount. Director James Cruze wanted her for his newest film, "The Enemy Sex." She accepted, and she and Cruze were married Oct. 25, 1925.

She quit Paramount again and began making several one-picture deals with various studios. It wasn't easy during these years because she soon found out the studios considered her a "has-been." However, she didn't let pride stand in her way, and made several Poverty Row quickies.

A 1928 interview in "Picture Play Magazine" said, "A few years ago, when Betty began to accept these quickie offers, comment was made that she was slipping. She was one of the pioneers to park her car unashamedly before the less pretentious studios. Then it became less reprehensible to appear in a quickie, and now it is almost fashionable.

"'What care I?' she asked. . . 'They offered me good money and 'my girl' some fascinating situations.'"

She and Cruze were having a very rocky marriage, splitting up several times and then getting back together. When they finally split for good, Cruze went bankrupt, and the creditors descended on Compson forcing her to sell quite a bit of her property.

Compson rebounded, however, and was cast in such successes as "The Big City" with Lon Chaney and "The Docks of New York" with George Bancroft. She almost played opposite John Gilbert in "Flesh and the Devil" when MGM was having some disagreements with Greta Garbo, but, of course, the disagreements were straightened out.

In 1928 came "The Barker" for which she was nominated for the Academy Award for Best Performance by an Actress. She lost out to Mary Pickford in "Coquette."

"The Barker" had some talking sequences, and Compson's voice came through so well she was offered many parts in the sound films that were being made in those early years. As a matter of fact, she was so busy, she turned down a part in Lon Chaney's only sound film, "The Unholy Three," but recommended her friend, Lila Lee, to Chaney who did get the part.

Throughout the thirties and forties, Compson had occasional film roles, performed on the stage and went on the vaudeville circuit. She also began a cosmetic line that cashed in on her name.

She married Irving Weinberg shortly after her divorce from Cruze, divorced him later, and during the forties married Filvius Jack Gall, a professional boxer. Together, they started a business called Ashtrays Unlimited which made personalized ashtrays for hotels, restaurants, etc. She continued the business on her own after her husband's death in 1962.

In 1928, Compson was interviewed while making "The Barker." Looking back over her career, she said, "My wickedness has kept me going. I wouldn't have lasted more than five years, possibly not that long, as an ingenue. Yet you cannot call my girl a stereotyped vamp. She has a business, a 'racket' of some sort, whereas the vamp's only occupation consists of breaking up homes. My girl, unless moved by jealously, doesn't stoop to such petty tricks. She never does dirty work just to be mean. She has no yellow streaks. Often she is a victim of circumstances. She is morally 'bad' through love, or she is placed among crooks and knows no better life."

Compson passed away April 19, 1974, at 77 years of age financially secure. She once commented, "There will never be a benefit performance for Betty Compson."

copyright 1998 by Tim Lussier. All rights reserved.