Produced by Universal Pictures

Directed by Paul Fejos

New York Premiere: September 30, 1928

Cast: Barbara Kent (Mary), Glenn Tryon (Jim), Fay Holderness (Overdressed

Woman), Gustav Partos (Romantic Gentleman), Eddie Phillips (The

Sport)

We might begin with a couplet from Richard Wilbur's poem "Some Opposites":

Let's then go to a beautiful sequence in Paul Fejos's Lonesome

(1928), one of those suspended moments when silent film takes

flight as image and music wedded lift it onto a higher plane.

Two lonesome twentysomethings,

faceless nonentities among the millions living in New York City,

meet at Coney Island and fall in love in the short span of a day.

Forty-seven minutes into the film, golden trumpet horns flood

the screen as we hear the familiar melody of Irving Berlin's "Always."

Cue to hundreds of couples slow dancing on an endless ballroom

floor, and then dissolve to our lonesome couple, lost in bliss,

dancing alone in the clouds under an enormous silhouetted golden

moon touched by the equally golden skyscrapers of the city. All's

enchantment; all's fairyland. Ah, we think for them and for us:

if only it could last.

Two lonesome twentysomethings,

faceless nonentities among the millions living in New York City,

meet at Coney Island and fall in love in the short span of a day.

Forty-seven minutes into the film, golden trumpet horns flood

the screen as we hear the familiar melody of Irving Berlin's "Always."

Cue to hundreds of couples slow dancing on an endless ballroom

floor, and then dissolve to our lonesome couple, lost in bliss,

dancing alone in the clouds under an enormous silhouetted golden

moon touched by the equally golden skyscrapers of the city. All's

enchantment; all's fairyland. Ah, we think for them and for us:

if only it could last.

But Lonesome really isn't about moments of transcendence as much as it focuses on the miracle of their occurring at all against (and being threatened by) a backdrop of separateness, blinding inertia, and the terrifying specter of anonymity. An early intertitle reminds us that "In the whirlpool of modern life-the most difficult thing is to live alone." Shots of thousands of worn-down heels pattering on sidewalks and droopy heads swaying on subways underscore Fejos's intention, delineated in an oral history interview shortly before his death in 1963: "I wanted to put in a picture New York with its terrible pulse beat-that everybody rushes, that even when you have time, you run down to the subway, get the express, and then change over to a local, and all these things; this terrific pressure which is on people; the multitude in which you are always moving but in which you are still alone; you don't know who is your next-door neighbor."

Since these words carry more than a bit of left-brain objectivity,

one isn't surprised to learn that Fejos later moved to directing

ethnographic documentaries of the Third World before becoming

an anthropologist and heading a foundation for anthropological

research. Philip Lopate, in his

superb essay accompanying the Criterion DVD of Lonesome,

notes that "This ethnographic curiosity should be borne in

mind while watching the stunning, evocative, documentary-like

passages of Lonesome, which capture New York in all its

feverish vitality. What also needs to be stressed is that Fejos,

from the beginning, saw film as primarily a medium of moving images,

of visual poetry concerned with light and shadow, of stunning

effects for the eye's delight-in short, more allied with painting

than literature. His style combined the flowing camera work of

F. W. Murnau and the German school with the rapid-cutting montage

sequences of the Russians."

research. Philip Lopate, in his

superb essay accompanying the Criterion DVD of Lonesome,

notes that "This ethnographic curiosity should be borne in

mind while watching the stunning, evocative, documentary-like

passages of Lonesome, which capture New York in all its

feverish vitality. What also needs to be stressed is that Fejos,

from the beginning, saw film as primarily a medium of moving images,

of visual poetry concerned with light and shadow, of stunning

effects for the eye's delight-in short, more allied with painting

than literature. His style combined the flowing camera work of

F. W. Murnau and the German school with the rapid-cutting montage

sequences of the Russians."

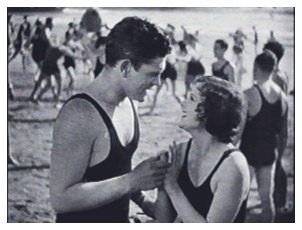

Small wonder, then, that after we're introduced to Jim (Glenn

Tryon) and Mary (Barbara Kent) as they awaken and scurry to their

workstations (he is a punch presser; she, a telephone operator),

the monotony of their work lives paradoxically is conveyed through

dizzying kaleidoscope. As clock hands revolve in the background

with deadening slowness, the camera moves back and forth between

their jobs as she connects switchboard cables underneath superimposed

faces chattering at their telephones with curiosity, love, anger,

or desperation; and his punch, punch, punch gets viewed from angles

high, low, back, front, straight, skewed, near, and far. Energy

here lies in depiction, not in the monotony of the jobs themselves.

Real, pulsing life seems a great distance away.

But when the factory whistle goes off (see if it doesn't remind

you of the one in Lang's Metropolis) and our protagonists,

hungry for love and adventure, join thousands of others in flocking

to Coney Island, watch how Fejos's visual flair literally adds

pinwheels to their romantic awakening. The sunlight is glow enough

as they get to know each other; once night falls and the amusement

park lights blaze, so does the screen, with bursts of red, blue,

and yellow, thanks to the extensive use of tinting and hand coloring

to bring balloons, horns, and flashing neon to life. Yet here

too (and testament to Fejos's heart: he was much more than a scientist)

is where the film has its loveliest and most simple vignettes

as Jim and Mary laugh at their reflections in funhouse mirrors,

smile in a photograph booth, and win a dolly, all leading up to

the transcendent dance in the clouds.

What wafts this floating, suspended moment into the empyrean is its contrast to the bumps we've encountered along the way. Two bumps, to be exact, when the lovers-

[I can't say it. This website is Silents are Golden, for crying out loud.]

when the lovers-

[Breathe it not to Webmaster Tim, all right?]

when the lovers talk. Yes, you know: blah blah blah and all that. By the time Lonesome was made in 1928, talkies, if they had not yet fully arrived, at least had brayed enough for the public to want more. You've surely seen examples of how awkward the early ones could be. (Try watching Vidor's silent The Crowd and following it with Foy's talkie Lights of New York, made the same year, and see if you don't reach for a Prozac.) But they sounded a siren call that translated into profit margins, sure enough, so we have three dialogue sequences in all, two on a beach before the dance (the dance, mind) and one in a courtroom afterwards.

They're not terrible: Fejos, Kent, and Tryon were all dedicated professionals. But the dialogue is so couched in the shallow Gee Whiz and Oh Golly that I associate with TV sitcoms of the fifties; and the performances-earnest, eager to please, and laid on with a trowel-are just as indigenous and bad. (At one point, I kid you not, Tryon really did make me think of Wally Cleaver.) They're short; they make their point. And if I may borrow a phrase from Mark Twain, let us draw a curtain of charity over the rest of the scene.

For we have the remainder of the film, a little more than an hour in all before we reach the happy ending, and that's bounty enough. The restoration of the lone nitrate print that survived at the Cinematheque Francais and later the George Eastman House has been a labor of love: the image, though still worn in spots, has a wide palette of hues, the color effects beautifully rendered. The soundtrack in particular is now astonishingly clear, with the sweet lilt of "Always" as direct as it must have sounded in 1928. It's an altogether lovely film, easy on the eyes and ears and, when it soars into the clouds, most easy on the heart. Credit the vision of Paul Fejos, yes, but cue the immortal words of Irving Berlin:

Copyright 2012 by Dean Thompson. All rights reserved

For those who wish see more of Fejos' work on film, Criterion has included the 1929 silent feature "The Last Performance" starring Conrad Veidt and Mary Philbin. Released in both silent and part-talkie versions, this is the only surviving print - the silent version recovered from Denmark with Danish intertitles and retitled "De tolv klinger" ("The Twelve Swords"). It is somewhat puzzling that Criterion offers such a high quality DVD that boasts a superb restoration of "Lonesome," but chose to include an unrestored version of "The Last Performance" with the original Danish intertitles - only offering us a subtitle translation at the bottom of the screen. The print itself varies widely in quality, contrast being its main issue with scratches here and there. Criterion did include an excellent Donald Sosin piano score. The story is nothing original - an older hypnotist/magician falling in love with his 18-year old assistant - and, of course, she falls in love with young man who is hired as a helper. If you're surprised that the hypnotist/magician seeks revenge for losing the girl, then you appaently haven't watched too many movies. However, Veidt is perfect for the role, and Mary Philbin is probably at the loveliest of any of her silent films. Fejos' affinity for tracking shots and unusual camera angles is obvious throughout. Viewing the film, we want to like it more than we do - and feel that we could if Criterion had not simply passed it on "as is." Certainly, if "The Last Performance" was worthy of inclusion in this DVD set, then it was also worthy of some level of restoration, including English intertitles.

A second bonus feature is an early talkie directed by Fejos - "Broadway" (1929) with Glenn Tryon, Merna Kennedy and Evelyn Brent.