Mack Sennett (King of Comedy, Doubleday & Co., 1954)

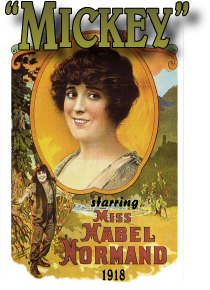

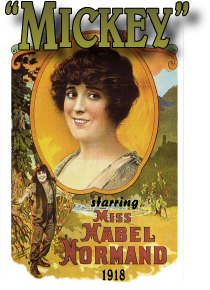

"It was a simple story, no more than the adventures of a pretty daughter of a Western prospector who comes to New York as a Cinderella, inherits great wealth, and is pursued by the rascally villain. . ."

" . . . in the end we came through with a film that I knew was a handsome and funny production, by far the best thing ever done with Mabel Normand. It gave scope to her whimsical talents for the first time. . ."

""Mickey" is probably the greatest Cinderella storyin the history of motion pictures. It is the only film I know of that sat in the ashes so long before making good. It moved on to Broadway, on to Chicago, Philadelphia, Boston and the other great cities, and its opening were cheered and applauded everywhere. . ."

"By comparison with modern motion pictures

with sound and perhaps color, "Mickey" of 1916-17 seems

absurd in  some

sequences. But the photography is sharp . . . the comedy scenes

are hilarious, the chases are breath-taking. And Mabel Normand

is prettier than a speckled pup. "Mickey" is still playing

here and there. In the intervening years I lost all track of accurate

box office records, and I do not own Mabel Normand's wonderful

picture today. But tradepaper accountants tell me that "Mickey,"

the picture nobody would look at, has grossed more than eighteen

million dollars."

some

sequences. But the photography is sharp . . . the comedy scenes

are hilarious, the chases are breath-taking. And Mabel Normand

is prettier than a speckled pup. "Mickey" is still playing

here and there. In the intervening years I lost all track of accurate

box office records, and I do not own Mabel Normand's wonderful

picture today. But tradepaper accountants tell me that "Mickey,"

the picture nobody would look at, has grossed more than eighteen

million dollars."

Betty Harper Fussell (Mabel - Hollywood's First I Don't Care Girl - The Life of Mabel Normand, Limelight Editions, 1992)

"Of the films that remain, it comes closest to capturing her infinite variety. Her instinct was to play 'the moment,' and 'Mickey' is an anthology of movie moments bursting with life. 'There are mad races between trains and motors,' a contemporary critic wrote, 'rattling chases on horseback, and eye-flling ballroom scene, and everything else that is known to filmdom, even to having some 'eats'.' Unconditioned by the stage, Mabel helped liberate movies from the structure of the stage by replacing coherence with speed and variety of action. Mabel had no sense of story, but a strong sense of scene, and in 1916, she created the kind of movie entertainment that would become a formula for decades."

Anthony Slide (Fifty Great American Silent Films 1912-1920, Dover Publications, 1980)

"The many sides of Mabel Normand's screen personality were seen to advantage in 'Mickey.' Crude slapstick was represented by such scenes as the one in which a squirrel runs up Mabel's trouser leg. . . The tomboyish elements in Mabel's character were taken care of by a chase through a deserted house and a climactic horse-race sequence. Her natural grace and beauty were seen to advantage in a tastefully shot scene, shown at a distance, in which Mabel performs high dives in the nude. And there was even a hint of pathos. One need not look far for an explanation as to the quality of Mabel's performance. In a 1921 interview, F. Richard Jones (director) explained, 'I try to draw out the individual personalities of the players. And for this reason I never act out any of the play for them. As we pay for personality, why not develop it rather than endeavor to work it into something else.' In 'Mickey,' the director's style and the star's personality met in a perfect match."