"The Phantom of the Opera" is a silent screen

masterpiece and a masterpiece of cinematic art for any period

in movie history. That's a bold statement, especially when one

considers there are some aspects of the film that are not quite

perfect, but, the statement stands. Chaney's performance is superb;

the look of the film is excellent and key to the overall effectiveness

of the movie; it is emotional and  moves the

viewer; and the story is a true classic that was faithfully and

adeptly interpreted for the screen.

moves the

viewer; and the story is a true classic that was faithfully and

adeptly interpreted for the screen.

Like "Ben Hur" (1926), "The Phantom of the Opera" was plagued with troubles, but the end result in both cases is a super piece of filmmaking that still intrigues viewers 75 years later. First of all, Universal/Carl Laemmle was committed to the film and spared no expense in its making. Over 250 professional dancers were hired for the ballet sequences; the Bal Masque sequence was shot in the very expensive two-color Technicolor process; the first steel and concrete stage ever built in Hollywood was constructed for the stage; and the Opera House interior and subterranean cellars are huge and magnificently done. The chandelier is even a faithful reproduction of the one found in the real Paris Opera House.

Although the film was first previewed in January, 1925, in Los Angeles, the reception was not good. Additional shooting and re-editing were ordered. Another preview in April still did not bring the desired results, and more work was done. Finally, after many changes and a completely reworked ending, the film premiered in New York in September to mixed reviews but fantastic reception from the audiences.

Variety magazine referred to it as a "revolting sort of tale," and The New York Times said it was "mechanical." So why did fans flock to see the movie, and how did it end up on many of the top ten lists of films for 1925? Most of the credit can go to Lon Chaney. Between his make-up (probably the best he ever did) and his performance, the film couldn't miss. The famous unmasking scene is still considered one of the most effective scenes from a horror movie ever.

Michael F. Blake, in his wonderful book Lon Chaney The Man Behind the Thousand Faces, (The Vestal Press, Ltd., 1990) gives some insight into why Chaney's performance was so outstanding. "While wearing the mask, Chaney's Phantom is confident of himself and afraid of no one. When Christine rips off the mask, however, his confidence turns into rage . . . Chaney then raises his hands above him, looking up to the heavens as if to call damnation upon the girl. His uplifted hands start to shake with fury and he bends down to Christine . . . 'Feast your eyes glut your soul on my accursed ugliness!" he cries, laughing maniacally. Then, just as suddenly, he stops. Pushing himself away from her, he realizes she has seen his dark side and his hopes of winning her love are destroyed. Chaney covers his face in his hands, his body slumping, the face that sparked fear now drawn into a mask of tragedy. . . Chaney at first scares the hell out of the audience and then just as quickly is able to win their sympathy for his character."

Richard Koszarski said in An Evening's Entertainment (University of California Press, 1990), "With the chandelier sequence thrown away and an unsatisfying chase at the end, only the authority of Chaney's performance holds the production together."

Chaney brings the Phantom to life just as we imagine him when reading the famous Gaston Leroux novel. He looks absolutely terrifying at times, as he does when Christine invokes his anger by unmasking him. He elicits pity when he first brings Christine to his chambers and pleads his love for her. One of Chaney's best bits of "business" is when he emerges from the black lake after killing Raoul's brother. He puffs out his chest, looks back in the direction of the foul deed, and grins evilly as he brushes his hands together. This scene is mildly amusing only because it makes his insanity so very evident.

Unfortunately, one of the main "targets" for the critics of the film is the acting of the other two leads Mary Philbin as Christine and Norman Kerry as Raoul. To say their performances are "wooden" would be putting it mildly. One could hardly say Philbin "reacts" to the Phantom. It's more as if she pauses for a moment when an emotion is called for, thinks about it, then gives forth with a very unconvincing expression. One such example is when she first agrees to go with the Phantom. She has heard his voice many times in her dressing room, but finally agrees to enter the secret doorway into the catacombs to follow her "master." She looks around slowly (excrutiatingly slowly) and sees no one. Finally, a hand touches her on the shoulder. With an unconvincing smile on her face, she turns and sees the masked Phantom, pauses (for what seems an interminable length of time), then registers fear.

Blake says, "The female lead, Mary Philbin, delivers the most glaringly inferior performance in the film; her broad and overdramatic gestures are what current audiences think all acting was like in silent pictures."

Kerry, on the other hand, is a stiff, cardbord lover for

her. He wears a uniform that is never anything less than perfect,

and one would swear it was starched for all the movement we see.

Kerry finally comes out of his coma in the final sequences where

Raoul and Ledoux  are searching through the cellars for

the Phantom's chambers. Kerry's performance is much improved when

Raoul and Ledoux are trapped in the room of many mirrors torture

chamber (although Arthur Edmund Carewe's Ledoux is still better).

are searching through the cellars for

the Phantom's chambers. Kerry's performance is much improved when

Raoul and Ledoux are trapped in the room of many mirrors torture

chamber (although Arthur Edmund Carewe's Ledoux is still better).

Blake contends that Kerry is not so much at fault and says his character was "reduced to a stereotypical leading man" which left him "little upon which to build his role."

One actor who almost never gets mentioned in connection with The Phantom of the Opera is Snitz Edwards. As the mousey and ever-frightened Papillon, he offers a delightful comic relief and a respite from the heaviness of the movie's suspense. Actually, after the movie's first preview in January, 1925, Chester Conklin was brought in to film some comedy scenes for what was considered a 'too-suspenseful" movie, but these were deleted before the New York premiere in September.

In his second book on Chaney (A Thousand Faces - Lon Chaney's Unique Artistry in Motion Pictures, The Vestal Press Ltd., 1995), Blake says, "The picture lacks style and the lighting to create the necessary mysterious mood." However, Koszarski believes that " . . . the film manages to express much of the eerie texture of the original Gaston Leroux novel."

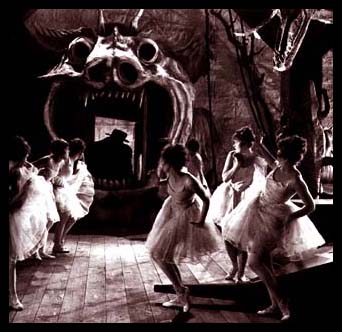

Actually, the backstage sets, the underground catacombs, the black lake, the Phantom's chambers all are impressive and, at the very least, eerily shadowed. As a matter of fact, all we see of the Phantom for a large portion of the story is his shadow. Shadows are used effectively throughout the film. When the ballerinas run backstage, strong, low lighting throws large, black silhouettes on the stone walls. At other times, we see the shadow of a cloaked figure gliding along the walls. Papillon encounters a huge, looming shadow of a hanged man on the wall. These are effective and do well at setting the tone of the film.

In Silent Stars (Alfred A. Knopf, 1999), author Jeanine Basinger says, " . . . the marvelous designs of the opera house with its subterranean channels are wonderfully photographed and made atmospheric by shadows, subtle lighting, and a cavernous appearance so real that you can almost hear echoes reverberating off the walls. In fact, the massive sets contribute a great deal to the terror the Phantom evokes. The vast spaces seem inhuman and menacing, an equivalent of the Phantom's soul."

It is only somewhat odd that these ancient, damp, cavernous cellars are so clean and immaculate. Some dinginess, cobwebs or even an occasional rat would have made the catacombs seem more realistic and a little more chilling.

The final chase resulting in the Phantom's ultimate demise

has come in for its share of criticism, too. As noted above, Koszarski

feels the final chase is "unsatisfying." An original

ending had the Phantom redeemed by Christine's kiss and leads

him to give the lovers their freedom. This was deemed by the studio

as "not logical or convincing." Comedy director Edward

Sedgwick was hired to come in and  film a new ending

- the chase through the streets of Paris. Certainly this is more

"satisfying" than a redeeming kiss, and, all things

considered, provides an appropriate, somewhat quick, end following

the heightened emotion and tension of the Phantom's battle of

wits with Raoul and Ledoux in the catacombs.

film a new ending

- the chase through the streets of Paris. Certainly this is more

"satisfying" than a redeeming kiss, and, all things

considered, provides an appropriate, somewhat quick, end following

the heightened emotion and tension of the Phantom's battle of

wits with Raoul and Ledoux in the catacombs.

Could "The Phantom of the Opera" have been better than it was? Virtually any film could have been better than what was finally shown on the screen, but that, alas, is all so very subjective. In spite of whatever shortcomings the film may possess, it does not lack for praise.

Joe Franklin (Classics of the Silent Screen, Citadel Press, 1959) says, ". . . there can be no complaint about the excitement the film does generate," and "It is rousing melodramatic fare, reaching a lively climax . . ."

Basinger says, "It's great stuff, and Chaney at the center is a magnificent figure."

"'The Phantom of the Opera' does show Chaney at his best," Koszarski says. "Furiously pounding his pipe organ, or staring madly at Mary Philbin with eyes of fire, Chaney becomes a gargoyle unmatched in twenties cinema."

Robert G. Anderson (in Faces, Forms, Films: The Artistry of Lon Chaney, Castle Books, 1971) says, "The film is still an effective one, even when viewed by today's more sophisticated audience. It tells its story and presents its characters as it was intended. The unmasking scene is still as dramatic as it was when first shown. . ."

It is interesting to note that in his An Evening's Entertainment, Koszarski reports a study that was done to determine the most popular films of 1922-1927 using a variety of data from the period including exhibitors' reports, etc. For 1925, "The Phantom of the Opera" was tied at fifth with "The Merry Widow" proving that in spite of any negative reports by the critics, the audiences loved it . . . and still do today as it remains, 75 years later, one of the most popular films of the silent era.

copyright 2000 by Tim Lussier, all rights reserved

Return to "The Phantom of the Opera" page

copyright 2000 by Tim Lussier, all rights reserved