Films such as "Walking Back" will never be found on anyone's top ten list, and may not even make a top 100 list of silent films, but it does give us some insight into Hollywood's view of the "wild, reckless youth" of the 1920's and serves as a superb cinematic "period piece."

In "Walking Back," director Rupert Julian (who also directed "Phantom of the Opera" three years earlier) was attempting to provide a combination of drama, excitement, youthful appeal and social commentary, as well. The excitement aspect works much better than the commentary, however, which, in viewing today, seems a little "cornball."

He endeavors to set the tone in the opening scenes with

titles like, "Cosmic Jazz the Universe" and "Somewhere

in this jazzy Scheme  our own cocky Earth

rattling around in Eternity like a mustard seed in a boiler."

No only is there no threat to Shakespeare here, it's also not

quite clear what he's trying to say. The next title states, "1928

and how" which is followed by a collage of scenes of

pianos being played, gangsters, dancing, a train racing down the

track, horse racing, and a car engine running which fades to a

speedometer quickly rising above the 60 mph mark. Another dissolve

takes us to two carloads of young people racing through the night

on a dirt road. When one carload of young people runs of the road,

the other carload of youth gets out and begins dancing on the

side of the road. Even a dangerous accident doesn't deter their

partying and thus the tone of the story is set.

our own cocky Earth

rattling around in Eternity like a mustard seed in a boiler."

No only is there no threat to Shakespeare here, it's also not

quite clear what he's trying to say. The next title states, "1928

and how" which is followed by a collage of scenes of

pianos being played, gangsters, dancing, a train racing down the

track, horse racing, and a car engine running which fades to a

speedometer quickly rising above the 60 mph mark. Another dissolve

takes us to two carloads of young people racing through the night

on a dirt road. When one carload of young people runs of the road,

the other carload of youth gets out and begins dancing on the

side of the road. Even a dangerous accident doesn't deter their

partying and thus the tone of the story is set.

When they steal an old truck and head to the local roadhouse, intertitles provide us with some questions to ponder "Viscious or just wild?" - "Godless or just graceless?" "Shameless or just young?" "Lawless or just reckless." The sermonizing doesn't stop here, though. Later when "Smoke" stomps out of the house in defiance because his father won't let him have the car, his father rants, "He's lawless, that's what he is lawless like all the rest of them today lawless." At that point, Mr. Thatcher's maid comes in and says, "Your bootlegger's here." There is some humor in the sequence, but, obviously, director Julian is also making a point.

Again, "Walking Back" may not be the greatest story ever written (it was taken from a novel entitled "A Ride in the Country" written by George Kibbe Turner), but it has moments of emotion that effectively move the viewer.

The relationship between "Smoke" and Patsy is typical, but effective, and serves as the motivation for the confrontation between "Smoke" and his rival, Pet Masters. Obviously, Patsy prefers "Smoke," but she's not going to resist the opportunity to make him jealous by threatening to go to the party with Pet if he doesn't come and pick her up within the next ten minutes. She tells "Smoke" on the phone that Pet has arrived and warns, "No foolin' in his Eighty Eight an' you know my weakness!"

In spite of his rebelliousness and disrespect toward his father, we can't help but sympathize with "Smoke" somewhat and the pressure his feels from his girl. Now that he has defied his father and left the house, the most important priority is to get an automobile. He realizes without one, Patsy will be spending the evening with Pet.

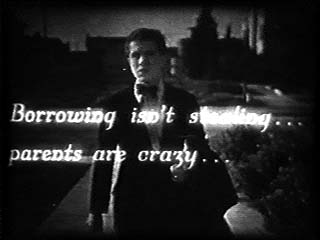

Although it's a bold move, "Smoke" decides to

"borrow" his neighbor's car. We are given a view into

"Smoke's" rationalization over his act in a unique way

his thoughts are superimposed in intertitles over the picture.

As he walks toward the house, the intertitles tell us  "Neighbor's

car . . . away over weekend . . . never know." "Borrowing

isn't stealing . . . Parents are crazy . . ." "Did

I ask to be born? . . . Borrowing isn't stealing." The method

of letting us into his thoughts is effective, and we can accept

his actions more readily because of it.

"Neighbor's

car . . . away over weekend . . . never know." "Borrowing

isn't stealing . . . Parents are crazy . . ." "Did

I ask to be born? . . . Borrowing isn't stealing." The method

of letting us into his thoughts is effective, and we can accept

his actions more readily because of it.

As noted, the movie succeeds at involving the viewer on an emotional level and providing some tension just as in the above-mentioned scene where "Smoke" agonizes over his decision to "borrow" the car. Probably, the highlight of the movie is the sequence at the club where "Smoke" tries unsuccessfully to avoid a confrontation with the bully, Pet Masters, but is forced into it anyway. Although Pet knocks "Smoke" down during an argument in the club, "Smoke" is convinced to let it go, and he and Patsy get in the car to leave. Patsy has even convinced "Smoke" that he must return the car immediately, the most "mature" decision we have seen in the movie so far or will see, for that matter.

However, as they try to leave, Pet just won't give up. He pulls his car in front of "Smoke's" refusing to let him pass unless Patsy stays. This is good stuff for the viewer as we put ourselves in his place and question what we'd do. Initially, we may consider "Smoke's" decision to enter into a demolition derby with someone else's car rather stupid, but we must be reminded of the circumstances. This is a classic situation for a teenager in that he must maintain his "dignity" with his girl and all of his friends all who are watching him at this moment to see what he'll do. It's a well-developed dilemma and makes for a good story. If he backs down, he's a coward in the eyes of his girl and all his friends. If he challenges Pet with his car, he will be ruining an automobile he isn't supposed to have in the first place!

Actually, the movie begins to falter after this point. It's pretty good drama for the first two-thirds, but the final third of the film dealing with gangster Beaut Thibeau is somewhat weak. There is corny humor presented through the intertitles with one of Beaut's hoods repeating everything he says while chewing on a toothpick and cleaning his nails. This may or may not have been "cliché" in 1928, but it most certainly is today. Beaut cannot even be taken very seriously as a dangerous gangster, partly due to the two thugs who accompany him.

We are also puzzled as to why he needs "Smoke"

to drive the car when he has his two hoods available. Actually,

one does participate in the  robbery with Beaut,

but the other stands guard over "Smoke" to make sure

he does what he's told. Very puzzling, indeed.

robbery with Beaut,

but the other stands guard over "Smoke" to make sure

he does what he's told. Very puzzling, indeed.

The wild ride through the streets following the robbery is somewhat exciting and provides a passable climax, and the crash into the police station offers an acceptable means of "capturing" the crooks. However, the sense of closure is just not there in the final scene. This is where "Smoke" expresses remorse for his actions, and all is forgiven by his father. Certainly he has earned a reward for his capture of the criminal which will pay for his neighbor's car, but he is still guilty of stealing an automobile and taking part in a robbery. Realistically, money and remorse just wouldn't seem to make all the troubles go away that "Smoke" has gotten himself into.

As for the actors, Richard Walling does a commendable job as the rebellious youth, and Sue Carol does a good job as the cute and coquettish girlfriend. However, acting honors should go to Arthur Rankin as Pet Masters who provides us a believable and thoroughly "nasty" nemesis for "Smoke" Thatcher.

All things considered, "Walking Back" is an enjoyable film and well worth adding to anyone's collection who loves the silents and would like to own a good, youth-oriented, Jazz Age film.

copyright 2001 by Tim Lussier, all rights reserved