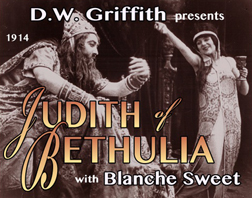

Produced by Biograph

Directed by D.W. Griffith

Cast: Blanche Sweet (Judith), Henry Walthall (Holofernes), Mae Marsh (Naomi), Robert Harron (Nathan), Harry Carey (a traitor), Lillian Gish (the young mother), Dorothy Gish (the crippled beggar), Kate Bruce (Judith's maid)

This is a Biblical story with all the trappings of a soap opera. It's about the siege of the Israelite city of Bethulia by the Assyrians complete with betrayal, loyalty, murder, Biblical characters, mass killings, decapitation, soldiers and weapons.

A pious and wealthy widow, Judith

(Blanche Sweet), conceives a plan to end the siege of the city

at a time when the beleaguered inhabitants are near starvation,

and, after forty  days, are ready to

surrender. The young widow dresses herself seductively as a courtesan

and goes to the enemy camp where she attracts the attention of

Nabuchodonosor's general whose army is laying siege to the city.

Judith offers herself to the Assyrian general, Holofernes (Henry

Walthall), after a wild night of feasting and revelry as a part

of her plan to save her city.

days, are ready to

surrender. The young widow dresses herself seductively as a courtesan

and goes to the enemy camp where she attracts the attention of

Nabuchodonosor's general whose army is laying siege to the city.

Judith offers herself to the Assyrian general, Holofernes (Henry

Walthall), after a wild night of feasting and revelry as a part

of her plan to save her city.

The reviews were favorable:

Variety, March 27, 1914: "It is not easy to confess

one's self unequal to a given task, but to pen an adequate description

of the Biograph's production of 'Judith of Bethulia' is, to say

the least, a full grown man's job."

The Moving Picture World, March 7, 1914: "A fascinating work of high artistry, 'Judith of Bethulia' will not only rank as an achievement in this country, but will make foreign producers sit up and take notice."

D.W. Griffith and the Biograph studios came to a parting of the ways when Biograph refused to produce any film exceeding two-reels. The Europeans, and most notably the Italians, were producing four, five and six-reel feature films, and Griffith was greatly impressed at what could be accomplished with longer films. Although Griffith denied seeing the Italian epic, "Quo Vadis?," Blanche Sweet recalled going with Griffith to a theater in New York to see the picture, and he was very impressed with the production.

Most of the movie producers were under the impression that the public would not be able to sit through a film exceeding 20 minutes. Biograph had already released a few of Griffith's two-reelers as single films, but without Biograph being aware of what he was doing, Griffith secretly produced his first four-reel film in 1913, "Judith of Bethulia," in Chatsworth, California.

At one

time during the shooting in Chatsworth Griffith was having difficulty

in getting Miss Sweet to get some feeling out of her performance.

After a few hours of cajoling, Griffith went on the stage and

gently, but firmly, said he needed Miss Sweet off the stage. Worried,

Miss Sweet pleaded with Griffith to take her back. After deciding

that she had begged hard enough, he took her back and obtained

the results he wanted from her for the remainder of the day.

At one

time during the shooting in Chatsworth Griffith was having difficulty

in getting Miss Sweet to get some feeling out of her performance.

After a few hours of cajoling, Griffith went on the stage and

gently, but firmly, said he needed Miss Sweet off the stage. Worried,

Miss Sweet pleaded with Griffith to take her back. After deciding

that she had begged hard enough, he took her back and obtained

the results he wanted from her for the remainder of the day.

Lillian Gish recalled that the lunch boxes that Biograph provided consisted of a sandwich-thick white bread with only a sliver of filling, cheese mostly; perhaps a hard boiled egg, a piece of fruit, and a half pint of milk.

Griffith had special titles made for the film with Frank Woods phrasing the captions in the style of speaking of the day. However, exhibitors fixed the titles to suit themselves in good "New Yorkese."

"Judith of Bethulia" was based upon a well-known play, and its religious theme had a "pre-sold" audience. Because the materials source was the Biblical Apocrypha, Griffith knew he could compete directly with the religious films coming out of Europe.

Moreover, the author of the play was the very popular Thomas Bailey Aldrich, a leading figure in the genteel tradition of American letters, the editor of prestigious and literary monthly, The Atlantic, and the author of the perennial favorite of the time, "The Story of a Bad Boy."

Biograph thought so little of the film that they didn't bother to release it until 1914, after Griffith had left the company.

On June 12, 1914, The New York

Times had a story with the lead stating "Disapprove Of

Long Reels - at a motion picture convention 1,200 exhibitors and

their friends want movies reduced to no more than 500 feet to

make a film story complete without the use of obviously unnecessary

matter."

Blanche Sweet, (1895-1986), was from

a family of stage performers. She went on the stage as a child,

and at the age of 14, she went to work at Biograph. The next year

she played her first famous role as the plucky telephone operator

in "The Lonedale

Operator" (1911), a film noted for its superb cutting and

camera placement. Sweet was quite different from most of Griffith's

feminine stars. Far from sweet and pathetic, she was tough and

self-reliant. Her greatest role while under Griffith is undoubtably

"Judith of Bethulia." After leaving Griffith, one of

her best performances was in "Anna Christie" (1923),

the first screen adaptation of the Eugene O'Neil play. With the

coming of sound, she returned to the stage and made only one film

appearance thereafter.

During an interview years later, Sweet recalled the filming of "Judith of Bethulia." "As I remember, Griffith's clarion call for a $50,000 production caused many a fainting spell in the front office," she said. "A $50,000 tragedy! Unheard of! Never been done! Crazy! Our fair-sized company of actors would all participate, some even playing two and three parts, beards and distance concealing identity."

Mary Wayne (Mae) Marsh (1895-1968) followed her elder sister Margaret to Biograph. Her first big break came as the lead in "Man's Genesis" (1912) because Mary Pickford and Blanche Sweet, among others, refused to perform bare-legged. Her reward was the lead in Griffith's "The Sands of Dee" (1912), a role that many of the Griffith's girls had desired. Those two films established her as a seasoned performer. She appeared in many Griffith films, and she can be seen in "The New York Hat," "The Battle of Elderbush Gulch," "Home Sweet Home," "The Birth of a Nation" and numerous other films. She left Griffith in 1916 for a lucrative contract with Goldwyn. Her roles for Goldwyn and other studios did not do justice to her ability, and she retired from the screen in 1925.

Harry Carey (1878-1947) was born Henry DeWitt Carey II in the wild open spaces of the Bronx, New York. He was the son of a lawyer, and he obtained his love for horses by watching New York's mounted policeman. After some stage work and touring with a theatrical group, he began his screen career in 1909 with the Biograph Studio that was located in the Bronx. He was usually cast as a villain by Griffith. When he signed with the Fox studio in Hollywood, his rugged, weather beaten look was ideal as a cowboy, and under the guidance of John Ford, he made many features and two-reelers as Cheyenne Harry. Throughout the silent era, in addition to acting, he also wrote scripts, produced and co-directed. He made a smooth transition with the coming of sound, and he then began playing supporting roles. He was nominated for an Oscar for his role in Frank Capra's "Mr. Smith Goes To Washington." His last screen appearance was in "So Dear to My Heart" released in 1948. Of his almost 250 films, he can be seen in many silent two-reelers and features including, "The Musketeers of Pig Alley" (1912), "The Burglar's Dilemma" (1912), "The Battle of Elderbush Gulch" (1914), "Blind Husbands" (1919), "Slide Kelly Slide" (1927) and "Trail of '98" (1928).

Sources: Movies of the Silent Years

by David Robinson and Ann Lloyd

Movies In The Age Of Innocence by Edward Wagenknecht

The Film Encyclopedia by Ephraim Katz

Selected Film Criticism by Anthony Slide

D.W. Griffith by Richard Schickel

When The Movies Were Young by Mrs. D. W. Griffith

The Movies, Mr. Griffith, and Me by Lillian Gish.

copyright 2001 by John DeBartolo, all rights reserved.

Contemporary

film reviews of "Judith of Bethulia" generally bestow

high praise on the movie and the actors. However, if one reads

comments by film historians, the views are somewhat mixed. Griffith

scholar Edward Wagenknecht (The Movies in an Age of Innocence,

University of Oklahoma Press, 1962) says the film is "heavy

and ominous from the first scene; it has a rich, brooding splendor

of imagination, as befits its semioriental subject; all in all,

it is certainly the greatest achievement of the early American

film." According to William K. Everson (American Silent

Film, Oxford University Press, 1978), "As a climax to

the Biograph films, 'Judith of Bethulia' disappoints" adding

that the film "might . . . have been improved had its length

been halved."

Contemporary

film reviews of "Judith of Bethulia" generally bestow

high praise on the movie and the actors. However, if one reads

comments by film historians, the views are somewhat mixed. Griffith

scholar Edward Wagenknecht (The Movies in an Age of Innocence,

University of Oklahoma Press, 1962) says the film is "heavy

and ominous from the first scene; it has a rich, brooding splendor

of imagination, as befits its semioriental subject; all in all,

it is certainly the greatest achievement of the early American

film." According to William K. Everson (American Silent

Film, Oxford University Press, 1978), "As a climax to

the Biograph films, 'Judith of Bethulia' disappoints" adding

that the film "might . . . have been improved had its length

been halved."

The length of "Judith of Bethulia" is a valid point for criticism. Admittedly, one of the weaknesses of the film is that the story line does not lend itself well to four reels in length. There is one story here, that is, one plot and no subplots. Put simply, the city of Bethulia is attacked. Judith decides to save her city by risking her life to end the life of their attacker, Holofernes. She goes to his camp, quickly wins his favor, and accomplishes her mission. Story over.

It is true Griffith did attempt to include something of a subplot with the love affair of Nathan and Naomi. Naomi is captured by the Assyrians, and when the army of Bethulia overruns the Assyrian camp, Nathan saves her at the last moment from a burning tent where she has been tied up - a typical Griffith last-minute rescue. However, it carries none of the suspense or intensity of Griffith's other such rescues.

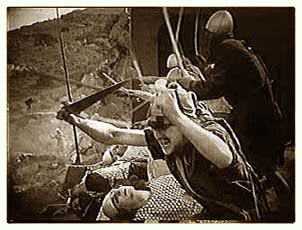

Everson also criticizes the battle

scenes. "The garb of the opposing armies was virtually indistinguishable,

and the action scenes became directionless skirmishes in which

identical extras were absorbed into a background of dust, rocks

and sun-dried grass and foliage." Sadly, Everson's criticism

is justified. The battle scenes are impressive for their size,

however, little about them makes us sit on the edge of our seats. No doubt, real battle in that period

looked very much the way Griffith portrayed it, "directionless,"

as Everson described it. However, there are no close-ups of individuals,

confrontations between two soldiers, moments of heroics, or moments

of tragedy. We are viewing the action from afar rather than being

right there in the middle of the conflagration.

seats. No doubt, real battle in that period

looked very much the way Griffith portrayed it, "directionless,"

as Everson described it. However, there are no close-ups of individuals,

confrontations between two soldiers, moments of heroics, or moments

of tragedy. We are viewing the action from afar rather than being

right there in the middle of the conflagration.

However, we must be careful not to be too critical of this film. One point on which all reviewers, those in 1914 and those today, agree is the acting of Blanche Sweet as Judith. Everson said it is "valid today and deserves a better showcase but which must have seemed outstanding in its day." Anthony Slide (The Griffith Actresses, A.S. Barnes and Company, Inc., 1973) said Sweet's performance "was one of the early American cinema's supreme acting achievements." In spite of the praise, that is not to say Sweet doesn't give forth with some of the "exaggerated" gestures so typical of that period, especially when she is expressing anger at what the Assyrians have done to her city. However, take a look at the scene where she dresses herself in sackcloth and covers herself in ashes, and one can see a most sincere and moving performance of anguish and despair.

Historian Lewis Jacobs (The Rise of the American Film, Harcourt, Brace and Company, 1939) said the film was "without question, the ablest example of movie construction to date." He went on to make a very valid point. "A comparison of the usual puny Amercian film of 1913 with the opulent and vigorous 'Judith of Bethulia' proves Griffith's stature conclusively" - and that is what any critic of the movies should remember. Griffith was treading new ground when he made "Judith." Certainly there had been longer films and other epics (most notably by the Italians), but Griffith always seems to weave the best of film technique into a much better final product. "Judith of Bethulia" is a great film, and Jacobs is right about other 1913 films being "puny" by comparison. "Judith" has its faults. That is true. But it is good entertainment, polished (for the most part), pictorially appealing and presented with class.

copyright 2001 by Tim Lussier, all rights reserved

Return to "Judith of Bethulia" silent film page