First National Pictures

Cast: John Bowers (Arthur Wellington Moore), David Butler (Bill Hendricks), Colleen Moore (Gwen), Harry Todd (The Old Timer), James Corrigan (Col. Fred Ashley), Donald MacDonald (The Duke), Kathleen Kirkham (Lady Charlotte)

The Rev. Arthur Wellington Moore has been sent by the church

to a small "wild-west" style town in Canada called Swan

Creek. His first stop is the local saloon, aptly named "The

Stopping Place." There he encounters a wild bunch of cowhands

led by ranch foreman Bill Hendricks. Moore, who is nicknamed "The

Sky Pilot" by the cowpokes, asks about using the saloon for

church services the next day. Bill offers to help and convinces

the saloon-keeper to oblige.

The next morning, a good crowd arrives along with Bill and his rowdy cowpokes. During the service, Bill is so disruptive, Moore asks him to leave. When he refuses, Moore takes him by the arm to put him out, and a fight ensues.

In spite of this confrontation, the two become close friends, and Bill even gets Moore a job on his ranch as a cowhand. Moore is soon introduced to the Old Timer, who resents God because of the death of his wife

Moore's first meeting of the Old Timer's daughter, Gwen, comes when she rescues him from being swept down the river and takes him home to dry out. When her father comes in and it's revealed Moore is a "Sky Pilot," both Gwen and her father tell him to leave.

At one point, Bill tells Moore the only way he will gain the respect of the cowpokes is to " . . . show 'em you're a man, and them make 'em listen to you." Moore's first opportunity to gain their respect comes when a drunk cowhand comes back to the bunkhouse and shoots up the place driving everyone else out. Moore bravely goes in and disarms the man.

Moore soon becomes good friends with all of the men on the ranch and gains favor with the Old Timer and Gwen when she falls off her horse and he saves her from a cattle stampede. The Old Timer turns back to God when he learns that Gwen has been paralyzed for life from the fall. To make matters worse, the stampede came about when the Old Timer and a bad guy known as "The Duke" were rustling cattle and Gwen tried to stop them.

The story doesn't end here. A church is built, then burned down, and, of course, the Duke and his men must get their come-uppance. And, not surprisingly, it is the "Sky Pilot" with whom Gwen falls in love.

Because this is a King Vidor film, we know it will be a well-made, solid story. It was based on a novel by Ralph Conner, although Motion Picture Classic said, "The changes are so radical that you will hardly recognize the old opus."

We also expect fine photography from Vidor, and the opening

scenes are certainly dazzling - panoramic shots of snow covered

mountains with a river winding through them, forest-covered hillsides,

gently flowing mountain streams - all reminiscent of the  Ansel

Adams photographs that came some years later. Even the introduction

of the "Sky Pilot" is impressive. We see him ambling

along on a donkey holding a torn umbrella over his head, and silhouetted

against a sky filled with billowy clouds as the sun sets in the

evening. What's sad about this is that the original film was filled

with tints and tones that are not in the Paul Killiam print available

from Critic's Choice Video.

Ansel

Adams photographs that came some years later. Even the introduction

of the "Sky Pilot" is impressive. We see him ambling

along on a donkey holding a torn umbrella over his head, and silhouetted

against a sky filled with billowy clouds as the sun sets in the

evening. What's sad about this is that the original film was filled

with tints and tones that are not in the Paul Killiam print available

from Critic's Choice Video.

Commenting on this, Vidor said, "What I believe I have actually done is to 'score' this photoplay for color. I have used a soft violet tint for scenes in which the earlier hours of the morning . . . are represented. For the period after sunrise, I have used a pale yellow tint; for noon, a faint amber; for night, a blue green tone on all objects casting shadows, high lighted with a warm amber.

"I have tinted the moonlight scenes with a carefully chosen deep blue tone, tinting the moon a faint, almost ethereal, amber, while I have used the conventional amber for interior night scenes. A delicate tint of green is used in all scenes of virgin nature where the day is supposed to be warm, while the Canadian northwest snow scenes I have used a steel blue tint." Vidor went on to note that he also used colors "to induce certain moods."

After we have been visually delighted by the opening scenes

of nature's grandeur, Vidor hits us squarely with the very rustic,

simple look of an 1800's frontier town. The saloon is something

reminiscent of a Bill Hart movie, and, like a Bill Hart movie,

it wastes no time in moving along. The stage is set immediately

for some tense excitement when the "Sky Pilot" plants

himself amongst the rowdy cowpokes in the saloon. Vidor manipulates

the viewer nicely by easing that tension somewhat when Bill befriends

the preacher and helps him secure the saloon for services the

next morning. However, when we see Bill and the cowpokes come

in the door with hands mockingly folded in prayer-like fashion,

the tension builds again and finally reaches a crescendo with

the fight between the two men. We're not let off this hook so

easily, though. The tension, coupled with a good dose of sympathy,

is still there as the cowpokes take  the "Sky Pilot"

out of town and run him off.

the "Sky Pilot"

out of town and run him off.

A typical western subplot is inserted after this. The Old Timer and "a self-styled English gentleman" named the Duke plot to steal a herd of cattle from Col. Ashley, Bill's employer, and drive them through a secret tunnel into the Duke's ranch. Unfortunately, the subplot is never really developed. It does, however, lay the groundwork for the injuries to Gwen. As the men are rustling the cattle, Gwen learns of the deed and rushes out to stop them. She falls off her horse right in the path of the stampeding cattle. The "Sky Pilot" comes along, jumps off his horse and stands above her waving the cattle to either side.

We are not told what happened to the Old Timer's wife, but earlier we were given a scene in which he picks up his Bible, handles it as if it disgusts him and throws it into the fireplace. In a moment, he has second thoughts and rakes it out with a stick. Thus, we are given some insight into the Old Timer who is obviously distraught at having lost his wife, and the only one he can find to blame is God. However, there must be some previous closeness to his faith or else why would he have a Bible in the house, and, also, what made him change his mind about burning the Bible?

When Gwen is brought in from her accident and they are awaiting the arrival of the doctor, the Old Timer falls to his knees and prays that God will spare her. As Bill and the doctor come in, Vidor gives us another beautifully composed scene. The cabin is almost dark, but there is the Old Timer on his knees, head turned upward, and hands folded in prayer with only his face and hands illuminated.

It is not known if the print viewed is complete or not, and some of the flaws that are about to be noted may be due to some missing footage. However, there are some shortcomings that should be mentioned.

One is the development of the character of the Duke. Outside

of a questionable attempt to steal cattle, we don't know what

his criminal activities are. Did this attempt to steal Col. Ashley's

cattle succeed? What was Col. Ashley's reaction to all this? Outside

of an original introduction, we never see him again. Also, although

there is a reference to the Duke's "gang," we never

really see them or know what wrong they do. In the end, the preacher's

church is burned down by a man Bill threw out of the church service.

The title tells us he saw this as an opportunity for revenge.

But, when Bill and his men catch the arsonist, he says he was

forced to do it by the Duke's gang. Is he telling the truth? We

don't know. However, Bill and his men go and burn down the saloon.

Why burn down a  poor man's business who, as far as we

know, has nothing to do with any of this? Also, how does this

adversely affect the Duke? These unanswered questions lead one

to believe something integral may be missing here.

poor man's business who, as far as we

know, has nothing to do with any of this? Also, how does this

adversely affect the Duke? These unanswered questions lead one

to believe something integral may be missing here.

It must be remembered, too, that this is early in Colleen Moore's career, and "The Sky Pilot" is not a starring feature for her. John Bowers takes the lead along with David Butler. Although Butler is excellent as the big, brawny, somewhat dumb, cowpoke, Bowers is rather lifeless as the "Sky Pilot." The real attraction is Moore of whom too little is seen in the film. She comes on with a bang as she is introduced riding full speed on a chariot-like vehicle behind two speeding horses, fully regaled in her cowgirl gear - chaps, wide-brimmed hat and all. She falls off the chariot and lies on the ground, eyes closed. For a second or two we think she is hurt, but then, with a full-faced close-up, we see her eyes open and a smile appear - a lovely shot that wonderfully displays Moore's beauty.

Jeanine Basinger commented on Moore's performance in "The Sky Pilot" in her book, Silents Stars (Alfred A. Knopf, 1999). "Her character suggests one Pickford might play. She has long, curly hair, and she's one half coy young woman and the other half feisty tomboy, bouncing from one to the other of these two selves in a somewhat confusing manner. . .

"Yet, Pickford imitation or not, Moore stands out immediately. Not because she has curls, like Mary, or can emote while temporarily crippled, like Lillian Gish, or because she plays her action as well as any serial queen, but because she is bold in the story and bold on film. She makes an impression because she's not just another passive beauty of the silent era. In retrospect, she looks like a girl crying out to be modernized, to be swept forward into the next decade and cut loose from earlier attitudes toward women. It's easy to see in 'The Sky Pilot' how the times were about to be very right for this distinctive, pretty, lively young actress."

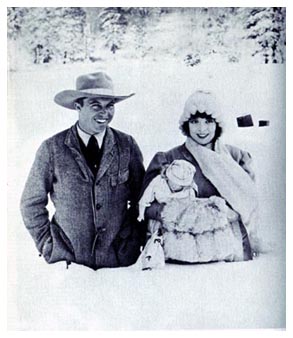

Reportedly, a romance developed between Moore and Vidor

during this filming. According to Eve Golden in Golden Images

(McFarland & Company, 2001), "In 1921 Colleen met

the man who - despite her later marriages - may have been the

love of her life. King Vidor was twenty-seven when he directed

Colleen for the first and only time in 'The Sky Pilot' . . . Colleen

and 'The Sky Pilot' cast and crew were conveniently snowbound

in northern California during the shoot, and a passionate romance

blossomed .

Moore doesn't admit to any such relationship in her autobiography, Silent Star (Doubleday & Co., Inc., 1968), . ." however, she does admit to being taken with Vidor. "King looked so nearly my age (Moore was 20 years old) when I bumped into him my first day there, I took him for an assistant director. A mighty handsome assistant director. He had the whitest teeth and the bluest eyes I'd ever seen, eyes that turned up at the corners, giving him a Tartar look. His hair was black and very straight and brushed back from a high forehead. All in all he was, as my grandma would say, a fine figure of a man."

Vidor obviously makes no mention of this romance either in his autobiography A Tree Is A Tree (Harcourt, Brace and Company, 1952). Instead, he focuses on how changes in the weather cost money, and the movie was barely completed on limited finances. "Across the railroad tracks from the village of Truckee (California) we had constructed the main street of a frontier town, complete with saloons and gambling dens. We had both summer and winter scenes to film. We had arrived in late fall, and the non-snow scenes had progressed as scheduled, though we still had two days of shooting without snow. The next morning, I was shocked to find it had been snowing all night with little sign of letting up for a day or two. Then panic overtook me. The end of the script called for the buildings to be burned down while deep snow covered the ground. We obviously could not set fire to them during the present snowfall because they were background for summer scenes still be to photographed."

Vidor said the company waited for days for the snow to disappear - all the while running up costs for a backer with limited finances. They finally decided to organized a "snow brigade" to shovel all the snow from the frontier town and the hills surrounding it. Once this was completed, he said they completed their two days of non-snow scenes.

Unfortunately, balmy autumn days followed

with no more snow in sight. This called for large amounts of salt

to be hauled in to replace the snow they had shoveled away so

filming could be completed.

Unfortunately, balmy autumn days followed

with no more snow in sight. This called for large amounts of salt

to be hauled in to replace the snow they had shoveled away so

filming could be completed.

According to Vidor, funds were depleted, and he even had to ask the cast and crew to finish filming without being paid. Although hounded by creditors, he said the picture was completed and taken to New York for distribution where he was reimbursed for all costs.

The New York Times said, " . . . despite some obtrusive faults and an overdone ending, it is a corking melodrama." The reviewer added, "Pictorially it is exceptional." Motion Picture Classic said "The Sky Pilot" was not the equal of Vidor's "The Jack-Knife Man," but felt it would be more popular with the exhibitors. It is not known how successful this picture was at the box office.

As noted, the print viewed is the Paul Killiam version which is distributed by Critic's Choice. The picture quality is good, although there are some lines in the film at various times. And, as mentioned before, it, unfortunately, has none of the original tints or tones. The musical accompaniment is an accordion, which, for a western, is acceptable, however, in two or three instances, there is a male singer accompanied by the accordion. One such instance is during the church service when a hymn is sung. This singing is distracting and totally inappropriate for a silent film. Also, the music on this tape is six or eight seconds out of sync with the movie. This is a flaw that was noticed in another Killiam/Critic's Choice release, "Three Bad Men."

copyright 2002 by Tim Lussier, all rights reserved