Lois Weber Productions

Cast: Claire Windsor (Amelia Griggs), Louis Calhern (Phil West), Philip Hubbard (Professor Griggs), Margaret McWade (Mrs. Griggs), Marie Walcamp (the other girl)

Let's consider the plot of this film as it's described on

the back of the snapcase: "The scholarly and underpaid Professor

Griggs and his family live in genteel poverty in a small college

town. To help out the family, beautiful young Amelia Griggs (Claire

Windsor) works in the public library. Next door to the Griggs

are the Olsens, a large and lively family of immigrants living

high on the hog, thanks to a thriving shoemaking business. Amelia

attracts the attentions of Phil West (Louis Calhern),  the

son of a college trustee and her father's laziest and naughtiest

student. His rival for Amelia's affection is Reverend Gates, a

gentle, sincere and impecunious minister.

the

son of a college trustee and her father's laziest and naughtiest

student. His rival for Amelia's affection is Reverend Gates, a

gentle, sincere and impecunious minister.

"When Amelia falls ill from overwork, her mother tries to nurse her back to health. With the cupboards bare, the very proper Mrs. Griggs is sorely tempted to steal a chicken from her neighbor's kitchen. The ensuing commotion turns out to be a blessing in disguise."

Now let me finish, briefly, the plot: Mrs. Griggs does steal the chicken but, overcome with remorse, places it back on Mrs. Olsen's table -- seen by both Mrs. Olsen, who looks on with disgust, and by Amelia, who sees only the theft, but not the return of the chicken. Phil, stung by the family's poverty, brings them a food basket, but the horrified Amelia returns to work to earn money and pay restitution to Mrs. Olsen. When Amelia faints in weakness and shame before her, however, Mrs. Olsen suddenly understands the desperation of the Griggs whom she had dismissed as standoffish and arrogant, and the neighboring families become friends. Phil West bring to his trustee father's attention the plight -- the "blot" -- of the grossly underpaid servants of humanity who care for people's minds and souls; and Amelia is left to choose between Phil and the Reverend Gates for her suitor.

It's true that the plot doesn't sound very commercial. No razzle dazzle, not loud attempts to entertain-- just a simple story of truth that is still relevant today. But once you start the film, look at the logo of "A Lois Weber Production": it's a quietly glowing lamp, the eternal flame of wisdom. That logo begins to tell you something about the remarkable woman who wrote and directed this work.

There were other women pioneers in silent film, of course,

but Weber towered head and shoulders above her peers of both sexes.

By the late 'teens she, with her husband and frequent co-writer

Phillips Smalley, was running her own studio and directing a staggering

number of films (only a few of which have survived,  unfortunately).

She was at one point the highest paid director on the planet;

and because of both her skill and her freedom to film stories

she thought worthy of serious attention, Weber was called "the

female D. W. Griffith." She boldly chose to focus on such

issues as abortion, drug abuse, poverty, and religious hypocrisy,

stunning her audiences with unsparing insight into these matters.

unfortunately).

She was at one point the highest paid director on the planet;

and because of both her skill and her freedom to film stories

she thought worthy of serious attention, Weber was called "the

female D. W. Griffith." She boldly chose to focus on such

issues as abortion, drug abuse, poverty, and religious hypocrisy,

stunning her audiences with unsparing insight into these matters.

And "unsparing" is often the word for "The Blot." True to what is admittedly a stereotyped character, Professor Griggs seems oblivious to the poverty of his calling. But his genteel wife, beautifully underplayed by Margaret McWade, notices everything; and through her eyes Weber points our attention to threadbare carpet, cracked shoes, worn and heavy-knuckled hands, and cats urged into neighbors' garbage cans to shift for scraps. With an equally unsparing eye and most effective cross-cutting, Weber points us to the glare of Phil's new car and the brook trout, spun sugar desserts, and mushrooms under glass at a country club banquet -- and we come to understand why Phil, now guiltily aware of Amelia's poverty and nauseated by the overabundance before him, turns and muses to a friend why some people have too much to eat while others have virtually nothing.

The cumulative power of these shots is touching enough (and "The Blot," for all its quietude, works at a powerful level of emotion throughout), but Weber -- like Griffith -- heightens the impact by drawing our attention to faces. We are moved by the compassion in Mr. Olsen's eyes as he watches Mrs. Griggs lead her cat to his garbage can; we are touched too when Phil, watching the Reverend Gates give alms to a weeping elderly woman, registers in his eyes his realization that this friend is a truly good and godly man. One of the most poignant instances occurs when Mrs. Griggs, crossing a fence to steal a chicken from the Olsen kitchen window, sinks in despair on the step, her face registering desperation, shame, and love for her family before hardening into determination as she rises once more. The realness of the moment is overpowering, not least because it is set in a real backdrop. As historian Kevin Brownlow surmises, "'The Blot' is the ideal film to show to those who did not live through them what the twenties were like in America. Thanks to a lighting technique invented by her old cameraman Del Clawson, Weber was able to shoot in real houses, so for the first time one can see what living spaces were really like, not what art directors imposed on them -- and what people really wore, not what fashion designers invented for them. The atmosphere is enhanced by some superb photography by Philip du Bois and Gordon Jennings; they are not afraid to let a face go dark on one side, or to show gloomy interiors as ill lit as they should be."

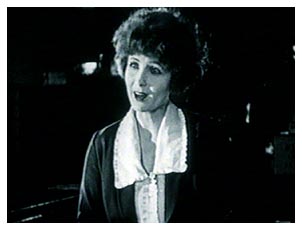

The documentary feel to the film is girded not only by the true-to-life locations, but by the performances as well; and in keeping with Brownlow's comment above, I would add that "The Blot" is the perfect film to show to those who think of silent film acting only in terms of semaphores and clenched hands to foreheads. Louis Calhern is entirely understated as he segues from naive, unthinking cad to morally outraged Samaritan; and the beautiful Claire Windsor, one melodramatic moment excepted, plays Amelia with light brush strokes of cool grace under pressure. But it is Margaret McWade who lingers in the memory: one understands from the first shot of her haunting face that here is a woman reduced to almost catatonic repression by years of doing without.

If "The Blot" is about underpaid servants of humanity and the shameful divide between the haves and have-nots, it is finally about possibilities. When Mrs. Olsen suddenly realizes that Amelia, beneath her cool exterior, is a frightened child; when Phil bullies his friends into joining him at nightly study sessions with Professor Griggs to bring the humble educator extra income; when he offers sincere companionship to the Reverend Gates -- the viewer's heart leaps with hope, as Weber surely intended. As Anthony Slide beautifully states, "'The Blot' is not a masterpiece in the same way in which, say, . . . 'Citizen Kane' is a masterpiece. But it is Lois Weber's masterwork, her greatest achievement, and one that succeeds in its very simplicity, in its adherence to presenting the simple and ordinary things of life. No matter our status, our education, our connections, each of us needs one another -- and each of us benefits from one another's friendship."

Weber died forgotten and in poverty in 1939. But we can be most grateful to Robert Gitt of UCLA for restoring her masterwork some 65 years after its premiere; to Kevin Brownlow and David Gill for presenting it with a fine score under the auspices of Photoplay Productions; and to Image Entertainment for the DVD. Weber's artistry and moral urgency still speak with moving directness to the human heart.

Works cited:

Kevin Brownlow, Behind the

Mask of Innocence

Anthony Slide, Lois Weber: The Director Who Lost Her Way

in History

Copyright 2005 by Dean Thompson. All rights reserved.