Paramount Pictures

Cast: Raymond Griffith (Jack), Virginia Lee Corbin (Alice Woodstock), Marion Nixon (Mae Woodstock), Montagu Love (Capt. Edward Logan), Mack Swain (Silas Woodstock), Silas Billing (Abraham Lincoln)

In American Film Criticism (Liveright, 1972), authors/editors Stanley Kauffmann and Bruce Henstell comment, "In an international poll of critics in 1972, 'The General' was voted one of the ten best films of all time. 'Hands Up!' is deservedly forgotten."

Walter Kerr responds in his book, The Silent Clowns,

(Alfred A. Knopf, 1975), "'The General' is what they say

it is: a masterpiece. But  'deservedly

forgotten' is surely the wrong phrase. For, without laying claim

to anything like the scale, the pictorial beauty, or the ingeniously

balanced structure of Keaton's film, 'Hands Up!' contains some

work that is daring - for its period, certainly - and some that

is masterfully delicate, the work of an inventive, unaggressive,

amiably iconoclastic intelligence."

'deservedly

forgotten' is surely the wrong phrase. For, without laying claim

to anything like the scale, the pictorial beauty, or the ingeniously

balanced structure of Keaton's film, 'Hands Up!' contains some

work that is daring - for its period, certainly - and some that

is masterfully delicate, the work of an inventive, unaggressive,

amiably iconoclastic intelligence."

Since Buster Keaton's "The General" was released the year after "Hands Up!" and maintains such a high reputation today, comparisons between the two films are inevitable. However, the comments from Kauffmann, Henstell and Kerr are sufficient commentary on the merits or "demerits" of the films as they relate to each other. The remainder of this review will focus solely on what "Hands Up!" has to offer - or fails to offer the viewer.

For those who have never seen a Raymond Griffith, a viewing of "Hands Up!" will present a comedian unlike any other from the silent era. Yes, the ill-fated French comedian Max Linder comes to mind, but only because we associate both comedians with the top hat and dapper dress. Linder's comedy most closely resembles the situational comedies of early television, dealing with exaggerated circumstances in a real world. Griffith was more likely to step outside the real world - no, not entirely in the sense of a Keystone comedy - but you will be more likely to see exaggerated slapstick and/or nonsense in a Griffith film. For example, although "Hands Up!" takes place during the Civil War, Griffith is able to distract hostile Indians by teaching them the Charleston. This anachronistic bit of humor obviously takes us out of the real world of the 1860's. In another scene, he is being hanged from a tree limb. A large number of men grab the rope and pull so hard that he is pulled up, across the limb and onto the ground on the other side - shades of Keystone.

Griffith's trademark, at least in "Hands Up!," is a self-confident, unruffled presence in the midst of the most difficult or threatening situation. This self-confidence, which comes across quite often as arrogance, takes us out of the real world, especially when he is faced with something so serious as a firing squad or a hostile Indian attack. Additionally, the firing squad and their commanding officer smack of the Keystone Cops in their incompetence. In Comedy is a Man in Trouble (University of Minnesota Press, 2000), author Alan Dale says, "Sporting a New Orleans's idea of Parisian evening dress, he's experienced in the ways of a rowdy, corrupt, man's world - a slapstick Rhett Butler."

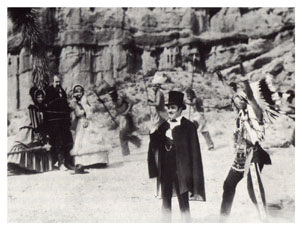

The film does have a very authentic look to it which adds to the enjoyment. Griffith and director Clarence Badger don't provide us anything close to an epic view of the Civil War, but the film's look does remain adequately true to the period. The opening sequence with President Lincoln and his cabinet is especially pleasing. Kerr said, "The assembled cabinet makes a tableau, very much in the D.W. Griffith manner, very much in the manner of any photograph or drawing of the Civil War period." Also, Silas Bilings, a silent movie unknown, plays a very convincing Abraham Lincoln.

The humor begins with a dissolve to the second scene we

see in the picture -- a small wooden cabin where Robert E. Lee

is shown with his attendant. The Confederate spy Jack (played

by Griffith) rides up swiftly, comes inside and quickly beats

the dust off himself - a huge cloud filling the room. Jack is

given his mission, and he and Lee shake hands. While they are

doing this, a cannonball rolls under the shack, and the entire

structure is disintegrated in the explosion. When the cloud of

smoke dissolves, the two men are still standing there shaking

hands oblivious to the destru ction

around them. This joke works well in that the result is totally

unexpected. The average silent comedy would have had the men in

rags, faces smutty and staggering about.

ction

around them. This joke works well in that the result is totally

unexpected. The average silent comedy would have had the men in

rags, faces smutty and staggering about.

The premise for the story is that Lincoln has sent his envoy, Capt. Logan, to Silas Woodstock in Nevada to secure the gold the Union needs to continue fighting. Lee has sent Jack as a spy to either retrieve the gold or keep the Union from obtaining it. We don't know how, but when we first see Jack in Nevada, he has been captured as a spy. He is in formal attire, complete with top hat and cape, and is being stood before a wall in front of a firing squad. All sorts of silliness takes place to keep the firing squad from completing their duty (for example, when they start to fire, he throws a plate in the air, and they fire at it), with Jack eventually escaping by painting a very realistic rendition of himself on the brick wall.

Next we see Jack on a stagecoach sitting with his back to Silas Woodstock and Capt. Logan as the two men talk about the gold. When they stop to pick up Woodstock's two daughters (played by Marion Nixon and Virginia Lee Corbin), the two men decide to sit on top of the stage for more privacy in their conversation. This, of course, leaves Jack inside with the two very beautiful young ladies.

The stagecoach ride, although overextended somewhat, does offer some humorous moments as he tries to become acquainted with the girls. Trying to think of something to break the ice, he pulls out a pair of dice, but decides against that. The girls are reluctant to become too familiar because they "haven't been introduced." The girls give him their cards, and he deftly crosses his arms as he reaches into the two side pockets of his vest and whips out a pair of cards - unfortunately a pair of aces. Smiling broadly, he holds the cards out for a moment waiting for the girls to turn toward him and take his cards - then, suddenly, realizing his mistake, he just as quickly puts the cards away and pulls out the proper cards. There is humor in the mistake, but Griffith adds to the humor by the skillful manner in which he displays the cards - much like a magician who has very suavely performed a trick.

Later he reads the girls a ghost story, which, although it provides weak humor, was considered accomplished pantomime by Kevin Brownlow (The Parade's Gone By, Bonanza Books, 1968). "An accomplished pantomimist, Griffith saw to it that an opportunity for mime was include din every one of his pictures. In the stagecoach-ride scene in 'Hands Up,' he recounted a ghost story to two young girls. Every event was described in mime, hilariously and brilliantly."

While these shenanigans are taking place inside the canvas-draped coach, there is an Indian attack going on outside. How could this be happening without the trio inside the coach aware of the ruckus? Woodstock was shown shooting at a jack rabbit earlier, so they assume that's what the shooting is all about. Also, because there was a bee buzzing about the stage earlier, the three mistake the whizzing arrows as the annoying bee buzzing by their faces.

When the Indians capture the group, Capt. Logan escapes,

but Woodstock is tied up ready to be burned at the stake. Jack,

in his usual self-confident manner, is unfazed by it all and somehow

communicates with the chief well enough to teach him to shoot

craps. We see the two emerge from behind a rock, and Jack has

apparently won all of the chief's garb, huge headdress included

- except his loincloth, of course.

Much of the remainder of the film is taken up with a battle of wits between Jack and Logan. Logan has a coach all loaded up with gold, but Jack manages to prevent his leaving with it. Finally, Jack figures his mission is accomplished when he is successful in blowing up the mine. Unfortunately, the explosion only succeeded in opening up an even bigger vein of gold.

The movie's climax is highlighted by a chase that is quite entertaining and funny. When Logan finally learns Jack is a spy, Jack escapes into Woodstock's house and ends up first in one daughter's bedroom and then in the other daughter's. In Mae's (played by Marian Nixon) room, he is shown opening an attic door and climbing up to hide. When Logan comes in, he looks up to see the tail of Jack's cape still hanging from the closed attic door. As he climbs on a table to get to the culprit, Jack appears from behind the door and escapes - an ingenious trick on the viewer. On the roof of the two-story house, he tries to escape the soldiers who are on the ground, but they shoot, and he falls down, disappearing on the back side of the roof. As the soldiers run to the rear of the house to capture him, we see Jack leap back onto the front of the roof - he wasn't shot; it was a ruse to get the soldiers out of the way.

Jack is finally caught and about to be hanged. How will he escape now? Suddenly, Mae gets an idea. She takes a ring from her mammy, rushes up to her father and Logan showing them the ring on her finger and pleading that they cannot hang her husband. It appears Jack is saved when Alice also runs up making the same claim. "Sufferin' Jehosophat! A bigamist!" Woodstock exclaims, and they tighten the rope to hang him.

"Hands Up!" is an enjoyable comedy that gets mixed reactions from viewers. Obviously, Kerr thought highly of the film. Author Glenn Mitchell (A-Z of Silent Film Comedy, B.T. Batsford, Ltd., 1998) said, "'Hands Up!' is regarded as one of the top handful of feature-length silent comedies . . . Griffith's clever approach - aided and abetted by producer/director Clarence Badger and screenwriter Monte Brice - is typified by the many imaginative touches . . ."

Unfortunately, "Hands Up!" is not "imaginative," and it's unclear whom Mitchell is talking about when he says it "is regarded as one of the top handful of feature-length silent comedies." There is very run-of-the-mill humor in it and nothing that stands out as a memorable sequence. The most remembered scene is at the end when Jack is obviously puzzled how he should go about choosing between the two girls - both of whom want to marry him. At that moment, he meets the famous Mormon founder Brigham Young who disembarks from a stage with his nine wives. The solution is found, and the final scene fades with a stage pulling way diplaying a huge "To Salt Lake City" banner on the back.

Griffith's character also fails. He is too confident and

cocky to either elicit sympathy or, more importantly, instill

any concern or tension in a dangerous situation because he is

too self-assured in these situations himself. Not once does he

show any fear or trepidation whether he will survive and given

situation regardless of how dire it may be. If the character feels

no apprehension, how can the viewer become emotionally  involved in the scene? This, again,

is where he continues to step outside the real world into the

absurd. A series of gags strung together never works - at least

not in feature films - the film must elicit some kind of emotion

from the viewer. "Hands Up!" doe not.

involved in the scene? This, again,

is where he continues to step outside the real world into the

absurd. A series of gags strung together never works - at least

not in feature films - the film must elicit some kind of emotion

from the viewer. "Hands Up!" doe not.

This is not to bash Griffith. Actually, one of Griffith's pictures - "Paths the Paradise" - is one of the most enjoyable comedies available today from the silent era. It is fast paced, full of surprises, and keeps the viewer on the edge of his or her seat for almost the entire movie. To see Griffith at his best, this is the film that should be seen. (For more on this film, see "Paths to Paradise" (1925) on our "Past Features of the Month" page). Another fine example of Griffith's comedic talent is the Bebe Daniels feature "Miss Bluebeard" (1925). Although a supporting role, he steals the picture as the suave, but always slightly inebrieated, Bertie. For a surprise role, see "The White Tiger" (1923) which costars Griffith and Priscilla Dean as a couple of crooks. Griffith gives a surprisingly exceptional dramatic portrayal. All three of these films are readily available for home viewing today from various sources.

Surprisingly, the usually critical New York Times gave the film a somewhat favorable review calling it "a ludicrously humorous farce" and a "bundle of mirth." Variety, too, praised the picture saying it was "a succession of screams of laughter." Praise was also given to the other players in the film, but the reviewer added, ". . . it's a Griffith, and Griffith solely carries the picture."

Credit is given to Mack Swain, who, by his very appearance, is always funny. No matter how serious the situation, Swain can play it in a straight manner and get a laugh. A story recounted by Brownlow in The Parade's Gone By gives some insight into both Griffith and Swain. Monte Brice, writer on "Hands Up!' said, "I've met a few stubborn people in my life, but he was about the tops." He noted that when someone steals Mack Swain's horse at the beginning of the film, and he comes out of his store with the line, "Nobody steals my horse and lives to warm the saddle," Griffith wanted to fire him. He claimed Swain was too funny. He was finally convinced that a change in Swain's hat would make him less funny.

Kerr, in an effort to deter the reader from making a hasty judgment about Griffith's personality, said, "Griffith, making a comedy, surely wasn't objecting to the fact that a supporting player - one with a long reputation as a comedian - was truly funny. He was objecting to the fact that Swain was funny-funny, using an extreme bit of costuming to play into a too easy laugh that would violate the film's style. 'Play it straighter' are the key words here."

The two daughters, Alice and Mae, are ably played by Marion Nixon and Virginia Lee Corbin. Although Corbin was barely 15 years old when the film was made, she, along with Nixon, provide an intriguing love interest. Griffith's flirtation with the two has a certain sexiness to it, and, surprisingly, it is the younger of the two - Corbin - who gives the better performance. The Variety reviewer said, "Marion Nixon and Virginia Lee Corbin play the leads, opposite the star, with the former girl featured in the program and billing, although Miss Corbin registered better as to appearance and work before the camera." Nixon was not an expressive actress, and certainly isn't well suited to playing a coquettish, eyelash-fluttering young girl. Corbin, who at 15, had already been in pictures almost 10 years, is much more attractive and expressive in her shyness and flirtation with the stranger who has arrived on the scene.

"Hands Up!" is simply one of those pictures - more so than most - that is a matter of taste. Griffith does not have the universal appeal of a Chaplin or Lloyd, but he is a talented comedian in his own way. "Hands Up!" is funny, but Griffith is a better comedian than this picture allows.

Copyright © 2005, by Tim Lussier. All rights reserved.