Samuel Goldwyn, Inc.

Cast: Vilma Banky (Barbara Worth), Ronald Colman (Willard Holmes), Gary Cooper (Abe Lee), Charles Lane (Jefferson Worth), Clyde Cook (Tex), Erwin Connelly (Pa), E.J. Ratcliffe (James Greenfield)

There's a fine plot synopsis of "The Winning of Barbara

Worth" (1926) provided by Jim Beaver at the Internet Movie

Database, for he offers just enough hooks without giving away the whole shebang. Let's hear it from

Jim:

away the whole shebang. Let's hear it from

Jim:

"Jefferson Worth finds an orphaned child in the desert

and raises her as his daughter, Barbara. When grown, Barbara is

beloved by Abe Lee, the foreman of her father's ranch and company.

When a rich land developer arrives with plans to irrigate the

desert, Worth joins forces with him. The developer's foster son,

Willard, falls for Barbara, and a rivalry develops between him

and Abe. The river is dammed, but the developer swindles the ranchers

and refuses to reinforce the weakening dam, as he no longer needs

it. An angry mob turns on Worth; Willard and Abe come near confrontation

over Barbara; and all the time, that dam is getting weaker...."

You can see, then, that the stage is set for a thundering climax -- an appropriate expression as I recall the screening of "The Winning of Barbara Worth" at this year's Cinevent: the applause for both Philip Carli's grand pianism and the film itself was tumultuous. Some eighty-odd years ago, Variety opened its own floodgates in its review of "Barbara Worth:" "Epic! Miraculous! For massiveness of production, this film is incomparable!"

Incomparable? I'm not so sure about that one: the previous year's "Ben Hur: A Tale of the Christ" offered far more in the way of sheer spectacle. But Variety's reviewer was spot on in assessing the magnitude of director Henry King's achievement at the helm: "King has performed a miraculous task.... Putting over the fine points of the yarn by showing a desert sandstorm and then showing the reclamation work ... was a mountainous job, well executed."

Very true. But for all the impressiveness of its scope, I'd venture to say that what one finally remembers best are the film's warmth and humanity -- a tribute not only to the actors (about whom more anon), but to King himself, who even today remains sadly underrated, hardly deserving of the "traffic cop" sobriquet bestowed on him by William K. Everson in American Silent Film (Oxford University Press, 1978).

For King's task was a daunting one even before the cameras

began rolling. For one thing, he carried the responsibility of

bringing to life an enormously popular best-selling  novel

by Harold Bell Wright. (Wright, though forgotten today, in his

era was noted for the enormous popularity of his fiction, if not

for its quality. In his notes accompanying the Cinevent screening

of the film, Michael Haynes amusingly remarks that a Literary

Review essay on Wright began with "There is a richness

in social satire ... in the works of Harold Bell Wright"

and ended with "April Fool!") Producer Samuel

Goldwyn had spent at least $125,000 in purchasing filming rights.

King then had to find a locale suitable for filming. As he related

to Kevin Brownlow for The Parade's Gone By (Bonanza Books,

1968) some forty years later,

novel

by Harold Bell Wright. (Wright, though forgotten today, in his

era was noted for the enormous popularity of his fiction, if not

for its quality. In his notes accompanying the Cinevent screening

of the film, Michael Haynes amusingly remarks that a Literary

Review essay on Wright began with "There is a richness

in social satire ... in the works of Harold Bell Wright"

and ended with "April Fool!") Producer Samuel

Goldwyn had spent at least $125,000 in purchasing filming rights.

King then had to find a locale suitable for filming. As he related

to Kevin Brownlow for The Parade's Gone By (Bonanza Books,

1968) some forty years later,

"I found the location up in the Black Rock Desert, Nevada, on the edge of Nevada and Idaho. This was an elevation of 6,000 feet and the most barren desert you have ever seen. But it was just right for our picture. We built a whole town up there. A railroad passed over by the mountain, and we had a railroad station put in. We had to haul our drinking water from two hundred miles away, although we drilled a well for showers and so on. Our camp could accommodate twelve hundred people, and we'd bring in another twelve hundred by train."

And the film does impress throughout with its finely controlled sweep: the two towns built by Jefferson Worth, the hordes of settlers, the desert expanse, the sandstorm, the flood (the latter very slightly dampened, pardon the expression, by the use of miniatures rather obvious to our CGI-trained eyes, but no matter) -- all are given panoramic display by King and his cameramen, George Barnes and Thomas Branigan. No doubt the sweep of the novel (which I have not read) dictated such. It comes as little surprise that Harold Bell Wright was a Disciples of Christ minister; the themes of barrenness and fecundity, of exodus, of fall and redemption, of hatred and forgiveness, all have Biblical echoes, as do some of the intertitles, even ("And there was great joy, and the young crops grew and flourished mightily"). These call for largesse of both scope and emotion, making the truth and subtlety of the film's performances all the more remarkable.

Playing the title character, Vilma Banky leaves what is arguably the finest memento of her frustratingly brief career. Guilty admission here, and with apologies to the shade of Rod La Rocque: I never "got" Banky until this film. Just the other night, in fact, I revisited her two films with Valentino, "The Eagle" (1925) and "Son of the Sheik" (1926), and -- nope. (Then again, all of the performances in both films seem a bit semaphoric --) But as Barbara Worth, she's incandescent, by which I mean both slam-bang gorgeous (aided in no small part by the beautifully sharp and detailed print -- "Barbara Worth," by the way, was one of the first films to be shot on panchromatic stock) and utterly believable. When she sashays around in her riding clothes in her first scene, she is (and remains) a pleasure to the eye; when she sits by a fountain with Ronald Colman and registers both caution and growing curiosity, you suddenly realize that there's no acting here, just being. She never overplays her hand; it's a quiet, impeccably modulated performance, leaving wistful thoughts of what her career might have been had not her Hungarian accent ended her career with the advent of sound.

By the time of "Barbara Worth," Ronald Colman

had made several films with Banky, building up a popular romantic

partnership several years before Garbo and Gilbert ignited the

celluloid even further in 1927's "Flesh and the Devil."

There's no denying that they look good together, and King sagaciously

points his camera time and again  to Colman's

chiseled face and dark, soulful eyes. Like Banky, he may be at

his best in the quiet scene by the fountain. His acting -- did

he ever give a bad performance? -- is as understated as ever.

But -- rueful admission this time -- I've yet to see a Colman

silent that really brings me over to his camp. Maybe we've all

been spoiled by the memory of that sable voice, so gentlemanly

and quiet. (I never can read the last sentences of Dickens's A

Tale of Two Cities without hearing Colman in the 1935 film.)

As long as Colman's Willard Holmes is in close-up or medium shot

here, all's well; but set him moving about in long shot, and (pardon

the expression) the jig is up. I thought my "Eww!" reaction

idiosyncratic until I read Louise Brooks's words to Brownlow in

The Parade's Gone By: "I discovered [in silent

film] that everything is built on movement. No matter how well

Ronald Colman played a scene, if you saw him lumbering across

a room in that hideously heavy way of his, it took all the meaning

out of it." At least Colman doesn't raise unintentional

giggles as he does in Ernst Lubitsch's "Lady Windermere's

Fan" from the previous year (in several shots, his flat-footed

walk is exactly like Buster Keaton's!), but he simply wasn't meant

for Western garb or action alone. We need the voice for a complete

picture, if you will.

to Colman's

chiseled face and dark, soulful eyes. Like Banky, he may be at

his best in the quiet scene by the fountain. His acting -- did

he ever give a bad performance? -- is as understated as ever.

But -- rueful admission this time -- I've yet to see a Colman

silent that really brings me over to his camp. Maybe we've all

been spoiled by the memory of that sable voice, so gentlemanly

and quiet. (I never can read the last sentences of Dickens's A

Tale of Two Cities without hearing Colman in the 1935 film.)

As long as Colman's Willard Holmes is in close-up or medium shot

here, all's well; but set him moving about in long shot, and (pardon

the expression) the jig is up. I thought my "Eww!" reaction

idiosyncratic until I read Louise Brooks's words to Brownlow in

The Parade's Gone By: "I discovered [in silent

film] that everything is built on movement. No matter how well

Ronald Colman played a scene, if you saw him lumbering across

a room in that hideously heavy way of his, it took all the meaning

out of it." At least Colman doesn't raise unintentional

giggles as he does in Ernst Lubitsch's "Lady Windermere's

Fan" from the previous year (in several shots, his flat-footed

walk is exactly like Buster Keaton's!), but he simply wasn't meant

for Western garb or action alone. We need the voice for a complete

picture, if you will.

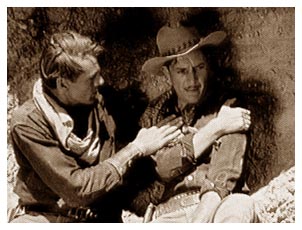

Which brings us to Gary Cooper. Now, "Barbara Worth" is part of the Gary Cooper MGM Movie Legends Collection DVD boxed set. The snap case cover gives Cooper the sole name above the title, but the back cover more straightforwardly admits that this supporting role was Cooper's first credited feature appearance. The story is well known that Cooper was a relative unknown from Montana when King saw him outside his office and was struck by his looks. Cooper had his heart set on playing Abe Lee, and King eventually acquiesced. As he recalled in David Thompson's Henry King, Director (Director's Guild of America, 1996):

"I started with a big party scene. I put [Cooper] in his wardrobe and put him in the back of the room. I said, 'Keep your eyes on Vilma Banky. Don't take your eyes off her.' I worked for about five days in this room and finally got to the part where Colman and Banky walk past him and out the door. I told him, 'Follow them' so he just followed them into the garden. In that sequence, it was just the three of them, and this boy was just bashful and awkward enough to be exactly right. He didn't have to act at all. I was pleased with that. I came back later and made some close-ups of him against the wall where he had been watching Vilma Banky, having people dancing by a couple of times so it wouldn't be so obvious I was shooting inserts."

And there you have it: twenty minutes into the film, those

close-ups stun as Cooper's shy, wistful gaze leaps off the screen.

No other moment in the film has quite the same impact. I don't

have my copy of Richard Schickel's The Men Who Made the Movies

(Ivan R. Dee, 2001) handy, but one of the profiled directors (Howard

Hawks, I think it was) mentioned to Schickel that the camera loves

certain faces. Even long-standing familiarity with that long,

handsome face doesn't diminish the power of these close-ups; quite

the contrary, in fact, for the face is far more vulnerable and

transparent than it became later with the onset (burden, perhaps?)

of stardom. From that point on, it's Cooper's film all the way.

Unlike Colman, he moves beautifully; watch him in his very first

scene, when he's surveying land. And  he's

even more understated and real than either of his talented co-stars;

watch as he pulls himself free from underneath a crippled horse,

for example, and also note the lovely (almost throwaway) vignette

when he sets Banky straight about her feelings for him. His performance,

like his cameo in "Wings" the following year, has DESTINED

FOR GREATNESS stamped all over it. No matter that Cooper went

to his reward almost half a century ago: watching his Abe Lee,

you can't shake the feeling that you're participating in some

discovery, some excitement at what was to come.

he's

even more understated and real than either of his talented co-stars;

watch as he pulls himself free from underneath a crippled horse,

for example, and also note the lovely (almost throwaway) vignette

when he sets Banky straight about her feelings for him. His performance,

like his cameo in "Wings" the following year, has DESTINED

FOR GREATNESS stamped all over it. No matter that Cooper went

to his reward almost half a century ago: watching his Abe Lee,

you can't shake the feeling that you're participating in some

discovery, some excitement at what was to come.

One other source of excitement must be mentioned: the flood sequence. Running some ten minutes, it's brilliantly edited, quite the equal of the chariot race in "Ben-Hur" or (closer to home) the land rush sequence in William S. Hart's "Tumbleweeds" (1925). Who edited it, though? The Internet Movie Database lists Viola Lawrence -- "Barbara Worth" being her first editing effort and a commendable beginning to a 34-year career that included editing credits on 89 films.

Grrrrrrrrr. Missing names!! Apologies for winding down this review with a growl, but by far one of the best things about this issue of "The Winning of Barbara Worth" is the score played on a 36-rank Wurlitzer Pipe Organ by the great Gaylord Carter at a 1971 screening of the film. The soundtrack is just a tad compressed, but it's still very clear, and Carter's hand is as sure and responsive as ever. WHY, then, is this kind and supremely talented man's name nowhere in evidence on the snap case or the DVD itself? This may well be the last "new" Carter score we'll have (though we can always hope), and to deny him due credit is just plain tacky.

But enough. There's spectacle, romance, humor, beauty, excitement, warmth, and talent aplenty in the 89 minutes of "The Winning of Barbara Worth." It's truly a grand show. Just prior to the waves of applause at the end of the Cinevent screening back in May, the concluding fade-out was accompanied by more than a few happy sighs. It was a lovely moment, beautifully summed up by an aforementioned intertitle: "And there was great joy."

Copyright 2007 by Dean Thompson. All right reserved.