A William Fox Production

Cast: George O'Brien (Dave Brandon), Madge Bellamy (Miriam Marsh),

Charles Edward Bull (Abraham Lincoln), Cyril Chadwick (Jesson),

Will Walling (Thomas Marsh), Francis Powers (Sergeant Slattery),

J. Farrell MacDonald (Corporal Casey), James Welch (Private Mackey),

George Wagner (Buffalo Bill), Fred Kohler (Bauman), James Marcus

(Judge Haller), Gladys Hulette (Ruby)

Adolescent Dave Brandon and his surveyor father set out from Springfield, Illinois, with the intent of mapping out a route for a transcontinental railway. The departure is sad because Dave must leave his childhood sweetheart Miriam. When Indians come upon their camp, Dave is luckily in hiding. One of the Indians, with two fingers on one hand, kills Dave's father right before his eyes. Some trappers come along and find Dave just as he has finished burying his father. Many years later, President Lincoln approves funding for the transcontinental railroad to be constructed by two companies - the Union Pacific Railroad Company and the Central Pacific Railroad Company. Miriam's father, Thomas Marsh, is in charge of the Union Pacific construction, and Miriam's fiancé, Jesson, is the chief engineer. Marsh must find a shorter route than sending the rail around the Black Hills due to a shortage of funds. Rich landowner Bauman wants the rail to go through his property and enlists Jesson to convince Marsh there is no shorter route. Pony Express rider Dave Brandon happens upon the Marsh train as he is running from Indians. He recognizes Miriam, and the two have a happy reunion - a reunion that is dampened by the introduction of Jesson as Miriam's fiancé. When Dave learns of the difficulty Marsh is having finding a shorter route, he tells him there is a pass he and his father discovered many years before that will provide what he needs. Marsh instructs Jesson to go with Dave and see this alternate route. While Dave is being lowered into a ravine by rope, Jesson cuts the rope hoping he has killed Dave. He returns to tell Marsh of the tragedy and that there is no shorter route than through Bauman's property. Dave returns but is convinced by Miriam not to confront Jesson. A huge Indian attack almost proves to be the end for all of the workers, but Dave hurries back to town to bring help. When Dave fights the leader of the Indians, he realizes this is Bauman - and he also finally gets a glimpse of his right hand - which only has two fingers!

Respected silent film historian William K. Everson called

"The Iron Horse" "one of the finest of western

epics." Certainly there were many that had come along between

the  premiere of "The Iron Horse"

in 1924 and when Everson wrote those words in 1978 - "The

Winning of Barbara Worth" (1926), "Cimarron" (1930),

"The Plainsman" (1937), "Duel in the Sun"

(1946), "The Searchers" (1956), "How the West Was

Won" (1962), "Once Upon a Time in the West" (1969)

. . . and the list goes on. But, "The Iron Horse" remains

a favorite of western films fans - silent or sound - and there

are many who agree with Everson's assertion that the film is "one

of the finest" ever made.

premiere of "The Iron Horse"

in 1924 and when Everson wrote those words in 1978 - "The

Winning of Barbara Worth" (1926), "Cimarron" (1930),

"The Plainsman" (1937), "Duel in the Sun"

(1946), "The Searchers" (1956), "How the West Was

Won" (1962), "Once Upon a Time in the West" (1969)

. . . and the list goes on. But, "The Iron Horse" remains

a favorite of western films fans - silent or sound - and there

are many who agree with Everson's assertion that the film is "one

of the finest" ever made.

Most of the credit obviously goes to director John Ford who had already proven his adroitness in the Western genre with such previous mini-gems such as "Straight Shooting" (1917) and "Just Pals" (1920) - two examples of the minimal extant remains from his early pre-Fox period. This was a unique period in Ford's career because a degree of freedom to write and direct was present as it would never again be in his career. By Ford's own admission, by the time he began with Fox in the early 1920's, many projects were handed to him for which he had "little or no affection."

Fortunately, "The Iron Horse" was a project of his own choosing, so it is not surprising that it stands out in film history head and shoulders above anything else he did during this period (although "Three Bad Men" (1926) is considered by some to be a more entertaining film).

As with all of his historical films, Ford insisted on authenticity. This is actually pointed out for us in the scene showing the coming together of the two locomotives from the Union Pacific and Central Pacific on May 10, 1869, at Promontory Point, Utah. Reminiscent of the intertitle footnotes in "The Birth of a Nation" (1915), the intertitle introducing this scene has a footnote stating, "The locomotives shown in the scene are the original Jupiter and #116." In Classics of the Silent Screen (Cadillac Publishing Co., Inc., 1959), Joe Franklin notes, "When one wasn't being impressed by the size of it all, there were interesting reconstructions of historical events - and persons - to watch, and a colorful use of many authentic props, such as Wild Bill Hickok's own vest-pocket derringer."

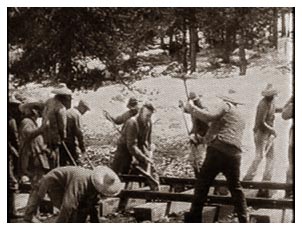

In order to make it all happen in a manner worthy of Ford and the historical scope of the story, the film was shot on location in the Nevada desert where he employed over 100 cooks, 5,000 extras, a regiment of U.S. Calvary from Salt Lake City, 3,000 railway workmen, 1000 Chinese laborers, and 800 Pawnee, Sioux and Cheyenne Indians. He used 2,000 horses, 1,300 buffalo (Franklin said he doubts this figure) and10,000 Texas steers. Fifty-six train coaches were used, two complete towns were built and a daily newspaper was issued recording births, deaths and marriages.

Ford's trademark has become the strikingly picturesque backdrops for his stories, but he doesn't make great use of his scenic vistas in "The Iron Horse" as he did more prominently in his films of the 1930's and 1940's. Nevertheless, the realism of the 1860's is conveyed with Ford's usual deftness. The viewer feels the bitter cold of the frigid winters and the debilitating heat of the desert sun. Characters, their dress, the sets, the props - all suspend the viewer's consciousness of the present time so that he is drawn as a time traveler to experience these historic happenings.

The players in "The Iron Horse" are not to be overlooked or underestimated for their contributions to the enjoyment of this film, either. Although George O'Brien never became a top-level star, his youthful exuberance is an essential element in making the character of Dave Brandon come to life on the screen. O'Brien's shy grin and boyish good looks seem at odds with the obvious physical presence he brings to the part - a combination that, nevertheless, lends himself well to both the romantic elements, as well as that of a rugged frontiersman who can ride, shoot and fight with the best of them. Fred Kohler, who superbly enacts the role of the villain, Bauman, is not slight of physique himself making the fight scene between him and O'Brien exciting footage. Although mentioned only briefly in this discourse, silent film fans should make note of the talent and presence that Kohler brought to the screen during the silent era. In any film in which he plays the adversary, the viewer always gets his money's worth of villainy (See "The Ice Flood" (1926), "The Spieler" (1928), and "Underworld" (1927).) - and he is at his best in "The Iron Horse."

Everson liked O'Brien's performance

saying, "George O'Brien made a relaxed and likeable hero,

and a most athletic one, clearly doing most of his own action

scenes . . ." Most contemporary reviewers were complimentary

toward his performance, but The New York Times (August

29, 1924) took their usual opposing viewpoint. "While George

O'Brien, who impersonates the heroic Davy Brandon, is quite good

in most of his acting, the producers have permitted him to have

too much of the show at certain junctures, especially where he

heaves his manly chest. In the fights with Cyril Chadwick, who

plays Peter Jesson, he is capable, although at times too theatric.

He seems to remember that he is a fine young specimen of manhood.

His shirt sleeves are tucked up high enough to give one a good

view of his biceps which appear to be frequently strained for

effect." The reviewer did, however, offer reserved praise

for Kohler. "Fred Kohler handles his role with restraint

and full effect."

Everson liked O'Brien's performance

saying, "George O'Brien made a relaxed and likeable hero,

and a most athletic one, clearly doing most of his own action

scenes . . ." Most contemporary reviewers were complimentary

toward his performance, but The New York Times (August

29, 1924) took their usual opposing viewpoint. "While George

O'Brien, who impersonates the heroic Davy Brandon, is quite good

in most of his acting, the producers have permitted him to have

too much of the show at certain junctures, especially where he

heaves his manly chest. In the fights with Cyril Chadwick, who

plays Peter Jesson, he is capable, although at times too theatric.

He seems to remember that he is a fine young specimen of manhood.

His shirt sleeves are tucked up high enough to give one a good

view of his biceps which appear to be frequently strained for

effect." The reviewer did, however, offer reserved praise

for Kohler. "Fred Kohler handles his role with restraint

and full effect."

Madge Bellamy offers a commendable performance - not that the script gave her a great deal of opportunity to shine. Her most dramatic scene comes when Dave has returned from the scouting trip with Jesson. While Dave is lowering himself into a ravine by rope, Jesson cuts the rope and returns to town thinking he has killed his rival. When Dave returns alive and well, Miriam begs him not to confront Jesson. She pledges her love for Dave, not Jesson, and so Dave agrees to her request. He does go to the saloon, however, with the intention of offering the "olive branch" to Jesson, but Jesson, a little drunk, pulls a gun on Dave. A fight ensues. Miriam arrives just as it ends and berates Dave. Dave tries to explain, "Listen, Miriam! I didn't come here to quarrel with him -" "Then you came to drink - and gamble - and - and dance," she says. "You came straight from me to this - vile den! You're as untrustworthy as he is!" Not the most challenging scene for an actress, but the emotion is present, and the ubiquitous "boy loses girl" part of the perfect story formula is accomplished.

Madge Bellamy was definitely one of the top beauties of the silent screen -- her large, soft brown eyes being her most outstanding trait. A better-than-average actress who played innocent, sometimes victimized (see "Love Never Dies" (1922), an excellent soap opera) young girls, her private life kept her from realizing the potential of her career. She was difficult and somewhat obstinate, which led to the end of her contract with Fox in 1928, and when she shot her millionaire lover in 1943, any hopes of a continued film career were dashed. Reviews of the film were not generally favorable or unfavorable toward Bellamy's performance. For example, the Picture Play (December, 1924) reviewer wrote, "Madge Bellamy as the heroine just keeps on looking pretty throughout the picture . . ."

George O'Brien was on a par with Bellamy as far as popularity during the 1920's. They both enjoyed the success of that second echelon of stars, but O'Brien's career played out differently as he proved to be a most congenial worker and made a successful transition into the sound era. Wisely, he moved into "B" westerns and enjoyed a very successful career during the 1930's. O'Brien had been in the Navy during World War I and was the heavyweight boxing champ of the Pacific fleet during that time. During World War II, he re-enlisted in the Navy, served in the Pacific and was decorated for his service. In spite of the popularity of "The Iron Horse," O'Brien is most remembered today for his role opposite Janet Gaynor in F.W. Murnau's "Sunrise" (1927).

The Charles Russell and John Kenyon script is very formulaic.

As noted earlier, we have the love story of Dave Brandon and Miriam

Marsh who were childhood sweethearts in Springfield, Illinois.

(By the way, a neighbor of theirs was Abraham Lincoln). It follows

the expected path of boy meets girl (childhood romance), boy loses

girl (Dave and his father leave to scout a route for the transcontinental

railroad), boy finds girl (after many years, the two are reunited

as adults), boy loses girl (the confrontation noted above over

the fight with Jesson), and boy wins girl back (happy ending,

of course). Another subplot, which may have been a little more

original in 1924 but has since become very commonplace, is the

lifelong search for the killer of his father. Of course, the only

clue Dave has to go on is that it was an Indian (actually Bauman

dressed as an Indian) with  only

two fingers on his right hand. As it should be with any epic story

placed against such an immense historical background, the experience

must be brought down to a human, personal level which is does

nicely with these entertaining, if not entirely original, subplots.

only

two fingers on his right hand. As it should be with any epic story

placed against such an immense historical background, the experience

must be brought down to a human, personal level which is does

nicely with these entertaining, if not entirely original, subplots.

Another essential of such a "heavy" story of this length is the presence of humor to ease the intensity of the viewing experience. J. Farrell MacDonald, a Ford stalwart, does a delightful job of interjecting some relief from the drama at strategic points in the story. There is an ongoing rivalry between MacDonald's character, Corporal Casey, and his Irish cronies and the leader of the Italian workers. Casey's brash temperament and Irish brogue (implied well via intertitles) make humorous scenes of otherwise serious ones such as the refusal of the Italian crew to work when the pay doesn't seem to be forthcoming or their refusal to join in fighting the Indians. A scene in a rather primitive dentist's office provides a short, comedic respite when Casey's fights against having a tooth pulled and it takes every bit of effort by the dentist and Casey's two closest friends, Sgt. Slattery and Pvt. Mackey, to hold him down in the chair. These three lovable characters also add contribute to the pathos of the story when Slattery is killed in the climactic Indian fight.

MacDonald is another one of those silent film character actors who brings so much to a film no matter what role he is given. For example, a dirty face and a quizzical expression where one eyebrow goes up while the other goes down are embedded in the viewer's memory long after this film is over. Ford's "Three Bad Men" (1926) is another film in which MacDonald gives a memorable performance.

As noted earlier, Everson still considered "The Iron Horse" to be "one of the finest western epics" in spite of minor shortcomings such as its "great length and its slow opening third" He went on to say, "Even its linking story - that old canard from the 'B' movies of the hero searching since childhood for the man who killed his father - is rather neatly interpolated into the main thrust of the story, and while it is unnecessary, it never gets in the way of, or delays, the epic sweep of the theme."

Throughout the film there are confrontations with the Indians, but the final climactic encounter with the "redskins" is worthy of comparison with almost any western since. Thoroughly authentic and "hair-raising," we are treated to a "Calvary to the rescue" ending in most rousing finish. However, in this case, it's not the Calvary. Dave, Casey and a small crew of workers are in the plains laying track when they come under attack by the largest onslaught of Indians they have encountered so far. What they don't know is that this attack was instigated by Bauman. Dave and Casey are able to back the train away from the fray and rush to gather reinforcements from town. Their return is delayed by the refusal of the Italian crew to go with them - on the basis that they have not received the beef they were promised. However, the expected cattle drive arrives just at that time, and the rescuers are on their way. Back at the scene of the fight, Indians are circling the train whose flatcars include both men and women shooting from behind railroad ties. Sgt. Slattery and one of the dance hall girls, Ruby, are shot, and for a time it seems the Indians may be winning the fight.

A short distance from the train is a stack of railroad ties

that have been set up in a semi-circular pattern so that a person

can walk inside and under them. Bauman, dressed as an Indian,

choose this as a vantage point from which to shoot at the train.

Dave, realizing there is a sharpshooter inside the ties, slips

over to the structure and there discovers  Bauman.

Catching a glimpse of Bauman's two-fingered hand for the first

time, he also realizes this is the man who killed his father so

many years ago. A stirring fight ensues, and the defeat of Bauman

coincides with the defeat of the Indians, as well.

Bauman.

Catching a glimpse of Bauman's two-fingered hand for the first

time, he also realizes this is the man who killed his father so

many years ago. A stirring fight ensues, and the defeat of Bauman

coincides with the defeat of the Indians, as well.

In referring to this climax, Franklin said, "It was magnificent, pulse-quickening stuff, slammed over with tremendous vigor and showmanship - and it's still just about the best such sequence ever put on film." Everson added, "The big Indian attack scenes are slammed over with tremendous gusto, with Ford's editing and camera mobility unstressed . . . but present and utilized only when necessary." (Note: The prevailing belief is that Everson "ghost-wrote" Franklin's book back in 1959. Note the similarity in the statements above.)

The only criticism of the final battle is the time it takes Dave and Casey to get the reinforcements back on the scene. There are only a handful of workers holding off what seems to be hundreds of Indians. The viewer is frustrated at the seemingly petty - if not unbelievable - refusal of the Italian crew to fight and rescue their fellow railroadmen because they had not received the beef they were promised. Ford may have stretched the believability level in this portion of the movie thereby weakening the impact of this crucial sequence for the viewer.

At well over two hours, "The Iron Horse" is certainly great in length, but it's also great in impact and entertainment. Ford has told his story well with a natural flow from one locale and dramatic vignette to another. The flavorful mix of the romance between Dave and Miriam, Dave's search for his father's killer, the humor of Casey and his compatriots, the hardships of everyday life for the builders of the railroad, life in the hastily assembled towns, the obstacles that had to be overcome to get the railroad laid through the treacherous terrain, Bauman's behind-the-scenes villainy, and the constant threat of Indian attack are all interwoven with cinematic acuity. Because of the sheer amount of story that must be compacted into the time allotted, it would be impractical to suggest any abridgement of Ford's masterful film.

As Franklin summed it up, "The Iron Horse" is an "exciting and actionful epic, and remains one of the biggest and best of all the super-western films."

Copyright 2007 by Tim Lussier. All rights reserved.