But what can be said about a film that has had almost everything said about it (praises, of course) that could be said? Well, hopefully there are a few behind-the-scenes tidbits that you may not have read elsewhere, and - at least in this reviewer's humble opinion - there are some absolutely wonderful sequences that historians tend to ignore.

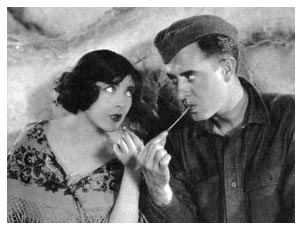

Let's start with the scenes. One of the most popular with

historians is the chewing gum sequence where Jim (Gilbert) introduces

Melisande (Adoree) to chewing gum. It is  certainly

an adorable scene that conveyed both the timidity and awkwardness

of two people in the beginning of a relationship yet hindered

by the fact they don't speak the same language. This scene has

been analyzed over and over, but there is at least one other that

is equally as charming between these two. But there's a lot of

fun leading up to that scene. This is how it happened.

certainly

an adorable scene that conveyed both the timidity and awkwardness

of two people in the beginning of a relationship yet hindered

by the fact they don't speak the same language. This scene has

been analyzed over and over, but there is at least one other that

is equally as charming between these two. But there's a lot of

fun leading up to that scene. This is how it happened.

Jim has an idea of hanging a barrel in a tree, filling it with water, placing a pan below with small holes, and, voila! They have a shower. So, Jim goes in search of a barrel. He does succeed in finding one, but it's heavy, and rolling it through the muddy street just doesn't work. So, he puts it over his head carrying it with hands down about thigh-height, and walks as best he can peering through a small hole in the barrel. In one hand, he has the pan, but, just as he comes upon Melisande (whom he has yet to see through the small barrel hole), he drops it. Since it's difficult to bend over and look down with a barrel over your body, he stoops and reaches for it. Having trouble locating it by feel, Melisande, who is beautifully laughing all the time, picks it up just as he is about to locate it. She holds it back to tease him a little longer, but then decides to hand it to him. When he realizes it has returned to his hand from somewhere up above the ground, the pantomime that follows is hilarious. Gilbert literally talks with his one free hand - waving it in the air, reaching down, and through these gestures making it obvious he is puzzled how he obtained the pan from about a foot off the ground! With his limited view through the hole, he looks down and around and finally see the hide of the cow that's next to him. That can't be it. Continuing to whirl around in his puzzlement, he finally sees the beautiful, smiling face of Melisande. He bends at the knees as the best bow he can give while wearing a barrel. Melisande bows. He bends at the knees again. He turns to go, looks back as if he's not quite sure, then moves to the archway in the wall, looks back with a bend at the knee and leaves. Words can't describe how humorous the scene is and what a wonderfully comical job Gilbert does with the barrel over his head.

Finally getting the shower rigged up, his buddies, Bull and Slim, strip down and take their showers. Now, this area is outside the wall of the village, but, nevertheless, it's open ground that can be seen from any distance around. Melisande just happens to walk to the archway in the wall, sees two bare derrieres, and begins to laugh. Jim, up in the tree feeding water into the barrel begins to shout at her to go away. She thinks the whole affair is hilarious (as do we!) and just waves back at him. The guys finally figure out what's happening and run for cover.

Now here's the charming scene referenced a few paragraphs ago. Jim climbs from the tree, runs up to Melisande (whom he has seen before) and they both have a good laugh. Looking down, Melisande notices one of his legging has become unwrapped and, by that, recognizes him as the man in the barrel! Through sign language she conveys who he is, and they both continue to laugh. Jim props his leg up on the wall to rewrap the legging, but Melisande waves him away that she will do it. Jim protests because it's covered with mud, but she refuses his protests, and does it anyway as he looks on smiling.

Through sign language and ridiculous attempts at speaking French such as, "Voo . . . and . . . me . . . vooley voo . . . take . . . little . . . petite . . . walk?" she agrees to walk with him down by the stream. Arm in arm they walk to a beautifully scenic spot by the water (one of many examples of the excellent cinematography in this film) - he bashfully but persistently trying to put his arm around her and she pushing his arm away. When they sit down, she is annoyed that he keeps running his finger along her arm or places his face close to hers as if he is going to kiss her. Suddenly, Bull and Slim show up with their aggressive method of flirting with a girl and push Jim aside. This doesn't last long, though, because when mess call is heard, they go running. Jim, however, gets only a short distance, looks back and sees Melisande watching him in puzzlement, turns to run again, then looks back and finally decides to return to her. Feeling it is appropriate to have one kiss before leaving, he does, and she surprises him by socking him on the cheek with her fist and knocking him to the ground. Lying on the ground, he looks up amazed and hurt and rubbing his jaw. All is well though when she smiles and takes pity on him, sitting down beside him and kissing the "hurt" to make it all better. With a broad smile on his face, Jim now takes advantage of the situation and points again to his cheek for another kiss, which she does. This goes on for three or four kisses until they both embrace, and the scene fades. The viewer can't help but smile at this lovely sequence, and it certainly ranks as equally or even more charming than the chewing gum sequence.

The march through Belleau Wood tends to get the most attention as the most famous sequence in the movie - and maybe it should. It's gripping and tense. The story has been told many times how director King Vidor used a metronome to keep cadence for a drummer who, in turn, banged out the rhythmic pacing for the filming as the soldiers marched through the woods attempting to overcome and survive the snipers in the trees and ingeniously camouflaged machine guns nests.

However, little is mentioned of the time the three buddies spend later that day and night trapped in a shellhole - that serves as their foxhole during the intense fighting - with the Germans literally a matter of feet in front of them. Any peep above the edge of the shellhole, and the bullets begin to fly ripping up the earth all along the top of their refuge. All they can do it wait. Daylight begins to fade. An intertitle describes the situation well. "Dusk - Silence . . . mud . . . The whine of shells . . . mud . . . silence." A plane flies overhead. Bull dives into an indention in the side of the shellhole and comes out covered in mud. Has the plane spotted them? He then opens a can of corned beef, but they are interrupted twice by exploding shells. Jim starts to light a cigarette, and Slim grabs it from his mouth and tosses it away. A fight almost ensues between the two until Slim points overhead reminding Jim of the plane. So they all try a chew of Slim's tobacco as an alternative.

A fellow doughboy crawls to them through a small trench telling them the "skipper" wants one of them to go get "that Fritzie with the toy cannon." They reluctantly agree to Slim's suggestion that they decide who goes by way of a tobacco spitting contest, which, of course, Slim wins.

Vidor knew how to create emotion on the screen - a film such as "The Crowd" is evidence of that, but no less so in "The Big Parade." The ensuing sequences take us to an emotional high with Jim back and forth like a trapped rat wondering if Slim is OK. Slim succeeds in his mission, but he is shot on the way back. When Jim and Bull hear Slim's moans, Jim is crazed with the fact his buddy may be dying and, in spite of an active machine gun still a short distance away, he daringly leaves the safety of their refuge to rescue his buddy.

Shift to a later scene - Following

an encounter with a German, Jim finds himself in a shellhole with

his enemy - Jim with a bullet in his leg and the wounded by

Jim and barely hanging on to life. As they fall into the shellhole,

Jim takes out his bayonet to finish him off. The young German

looks up at him - Jim starts once again to stab him - and again,

but disgustedly sets the bayonet aside and, instead, shoves the

German's face away from him. Both are exhausted, but the dying

German motions weakly for a cigarette. Jim places it in the young

man's mouth, lights it and then, as an afterthought, shoves the

German's face away again. Still thinking of his buddy out there,

the hatred for any German is no less intense. Jim turns to look

the other way and when he turns back, he notices the cigarette

has fallen out of the German's mouth. He places it back in, but

it falls out again. The young man is dead.

Shift to a later scene - Following

an encounter with a German, Jim finds himself in a shellhole with

his enemy - Jim with a bullet in his leg and the wounded by

Jim and barely hanging on to life. As they fall into the shellhole,

Jim takes out his bayonet to finish him off. The young German

looks up at him - Jim starts once again to stab him - and again,

but disgustedly sets the bayonet aside and, instead, shoves the

German's face away from him. Both are exhausted, but the dying

German motions weakly for a cigarette. Jim places it in the young

man's mouth, lights it and then, as an afterthought, shoves the

German's face away again. Still thinking of his buddy out there,

the hatred for any German is no less intense. Jim turns to look

the other way and when he turns back, he notices the cigarette

has fallen out of the German's mouth. He places it back in, but

it falls out again. The young man is dead.

Most film historians note that the famous shellhole sequence between Lew Ayres and the German in "All Quiet on the Western Front" (1930) owes its inspiration to this scene from "The Big Parade." According to Vidor, Gilbert had no instructions for the scene with the German soldier - it was entirely improvised. As for Gilbert's approach to the movie, Vidor said, "John never read the scenario. His reasons were quite sound and not due to laziness or disinterest. He argued that he wanted to be ready to do the scene as the director required, and he didn't want his mind to be cluttered up with a mess of preconceived ideas which would have to be expelled before he could follow the director's instructions. It made good sense, and it worked." (1)

The gum-chewing sequence was improvised, too. When Vidor arrived at the studio that morning, he needed a love scene but didn't know how it should take place or even where. He finally decided to have the couple filmed on the bench outside Melisande's home. Then, as he began to think through the action of the scene, he realized "neither of the two principal characters could speak the other's language, and the love play would, therefore, have to be in pantomime, a fortunate circumstance in a silent film. I was stalling for time. Then Donald Ogden Stewart, the humorist and playwright . . . wandered onto the set and after waiting fifteen or twenty minutes said, 'Come on, boys, let's see some action.' I laughed guiltily, turning to look at him, and noticed that he was chewing gum. Here was my inspiration. French girls didn't chew or understand gum; American doughboys did." (2) Thus, one of the most famous love scenes in silent movies was born.

A final scene that fails to be mentioned, yet is one of the most emotionally powerful in the movie is Jim's return to France to find Melisande. Following the war's end, John returns home to a hero's welcome, but his only concern is how quickly he can return to France to find Melisande.

The war is now over for Melisande, too, and she and her mother have returned to the village they were forced to leave and are trying to rebuild their lives.

We see a long shot of two women in a field plowing - Melisande and her mother. They stop, weary from their work. Melisande is also emotionally weary wondering if Jim survived the war and if she will ever see him again. They return to plowing, but Melisande looks up and see a strange figure on the hilltop in the distance. Only a silhouette, it is a man, limping with a cane - and before he is even close enough to recognize, she is sure it must be Jim and runs, even sliding down a hillside, until she reaches him on a tree-lined dirt road. What a magnificent ending to a masterpiece of filmmaking!

The idea of the film began when Vidor went to newly appointed MGM head of production Irving Thalberg with a concern. He told Thalberg he was weary of making "ephemeral" films that only had short runs. When he mentioned making a war picture, Thalberg asked if he had something in mind. Vidor responded that he had no particular story, only "an approach." He told Thalberg, "I wanted it to be the story of a young American who was neither over-patriotic nor a pacifist, but who went to war and reacted normally to all the things that happened to him. It would be the story of the average guy in whose hands does not lie the power to create the situations in which he finds himself but who nevertheless feels them emotionally. I said that the soldier doesn't make war. The average American is not overly in favor of it, nor abnormally belligerent against it. He simply goes along for the ride and tries to make the most of each situation that happens." (3)

Later, Vidor brought Laurence Stallings to California with five pages of story typed on onionskin paper. Stallings was a captain in the Marine Corps during the war and had lost a leg in Belleau Wood. He co-wrote "What Price Glory?" which had just recently made a big hit on the screen. Harry Behn and Vidor spent extensive time with the "elusive" (Vidor's term) Stallings listening to his stories - even following him to New York where Stallings had to return for other personal business. Satisfied they had the information they needed, Vidor and Behn hammered out the script on the train back to California.

To help him with the visuals and authenticity, Vidor viewed

and studied hundreds of reels of documentary film made during

the war due to the cooperation of the Signal Corps  of

the U.S. Army.

of

the U.S. Army.

Although Vidor wanted it much longer, he reduced the footage to 12,800 feet, with all the cuts he felt were possible. However, after it was previewed in New York, the distributing company ordered that it be pared down to 12,000 feet - explaining that because of its long running time, second shows would start late. and commuters would miss transportation. Vidor was working on another film at the time, but reluctantly took it home himself to edit, although he felt the film had been cut to its absolute minimum. "It occurred to me. . . that if I could cut three frames from the beginning and end of each scene, or six frames at each film splice, the total might add up to eight hundred feet." After many days of painstaking process, he still had 165 feet to go. "I went back and cut out one from on each side of each patch," and, with this, he said, he finally had 800 feet cut from the film. (4)

Also, as a result of its length, the film was originally shown with an intermission. The intermission took place when the Gilbert and his company were called up to the front and the emotionally final parting scene place between him and Adoree.

The film turned out to be the highest grossing film of the silent era, but, of course, Vidor had no idea its success would be so great when he finished it. He owned 20 percent of the film, but MGM offered him a large payment in lieu of the percentage. Vidor said he was working on another film at the time, so he hired a lawyer to negotiate for him. MGM warned in their negotiations that fewer than 10 films had ever grossed more than a million and half dollars. Vidor's attorney recommended he take MGM's offer. He took his attorney's advice and said, "thus, I spared myself from becoming a millionaire instead of a struggling young director trying to do something interesting and better with a camera." More than one source has quoted the production cost of "The Big Parade" to be $245,000, including Vidor's own autobiography. Kevin Brownlow quotes the production cost at $382,000 and a profit of $3,485,000. (5)

Interestingly, Vidor wasn't keen on the idea of John Gilbert playing Jim. He felt it was out of character for the "Great Lover" persona that was just beginning to identify Gilbert on the screen. According to Brownlow, Vidor couldn't envision "the immaculate leading man taking the part of a marine, but Gilbert entered completely into the spirit of the picture and gave a performance that ranks as one of the finest of the entire silent period." (6) Gilbert's portrayal is superb and markedly different from his many other "big" roles in films such as "Monte Cristo" (1922), "The Merry Widow" (1925), "Bardelys the Magnificent" (1926), "Flesh and the Devil" (1926) and others. He is very natural and restrained - almost to the point of nonchalance - except in the case of Melisande where greater enthusiasm is called for. This, however, fits perfectly in Vidor's goal to have a hero who "reacted normally to all the things that happened to him."

"The Big Parade" is also not a condemnation against war. "In the Great War many were wondering why in an enlightened age we should have to battle," Vidor told "The New York Times." "I do not wish to appear to be taking any stand about war. I certainly do not favor it, but I would not set up a preachment against it." (7) Therefore, "The Big Parade" is a very straightforward telling of a story, a fact that adds much to its realism.

Apparently, Gilbert saw "The Big Parade" as the pinnacle of his career. "'The Big Parade'!" wrote Gilbert. "A thrill when I wrote the words. As a preface to my remarks pertaining to this great film, permit me to become maudlin. No love has ever enthralled me as did the making of this picture. No achievement will ever excite me so much. No reward will ever be so great as having been apart of 'The Big Parade.' It was the high point of my career. All that has followed I balderdash." (8)

"The Big Parade" was also the highlight of Adoree's

career. Her performance is beyond any criticism. She absolutely

charms the socks off anyone who views this film, and, being the

second of five films the two would make together, it's obvious

they had an admiration for each other and enjoyed making films

together. The way Adoree looks up at Gilbert with a delightful

light in her eyes makes it obvious the on-screen chemistry necessary

for a film such as this was definitely there. In a 1982 "Films

in Review" article on Adoree's career, author Herbert G.

Luft, who saw the film upon its initial release, said, "Though

(Renee Adoree) later appeared as Musette in Vidor's 'La Boheme,'

she never matched the power of her performance in 'The Big Parade.'"

(9) By the way, Adoree could speak three languages fluently -

French being one of them - so her command of the language  certainly adds much to the authenticity of

the film - especially for lip readers!

certainly adds much to the authenticity of

the film - especially for lip readers!

Karl Dane and, to some degree, Tom O'Brien are there for comic

relief - and thankfully Vidor knew how to keep that in check so

that it's appropriate for this film - and they do an superb job,

as well. Dane's expressions are almost cartoonish with his long

face and wide eyes, but Dane is hard not to like. The comic element

did not detract from the sincerity of the friendship that developed

between these three and its impact on the second half of the film.

That said, some may take issue with how long the film takes to

get to the battle scenes and how much time was spent on scenes

such as settling into the village when they arrive, their life

in the hayloft, getting letters from home and the development

of the romance between Melisande and Jim - however, no film is

wasted. Again, the film is about people against a background

of war. Vidor understood character development - and when the

war truly did come into their lives, the previous character development

was essential for the emotional impact he desired. "The

film is a collection of fragile incidents," says in the DVD's

liner notes, "directed with such affection and care that

even the comic moments are strangely moving. Vidor's enthusiasm

is for ordinary people - there are no villains, no melodrama,

no heroics. And no lies." (10)

Sad to say, however, that three of our four principals characters died tragically young - Adoree in 1933 at age 35 from tuberculosis, Karl Dane in 1934 at age 48 from suicide, and Gilbert in 1936 at age 39 from a heart attack most likely resulting from his alcoholism. Tom O'Brien passed away in 1947 at age 57.

The film obviously received glowing reviews from every corner and has continued to be praised as a grand cinematic achievement until today. Carl Sandburg reviewed the film saying, "And 'The Big Parade' tells more about the war than any one picture, and probably more than all other war pictures put together. . .And, oh! It's something to talk about - the last half of this picture - and something to sit speechless and think about." (11)

In his "Life Magazine" review, Robert Sherwood said, "I could not detect a single flaw in 'The Big Parade,' not one error of taste or of authenticity, and it isn't as if I didn't watch for these defects, for I have seen too many movies which pictured the war in terms of Liberty Loan propaganda. 'The Big Parade' is eminently right. There are no heroic Red Cross nurses in No Man's Land, no scenes wherein the doughboys dash over the top carrying the American flag." (12)

Fifty-three years later, silent film historian William K. Everson, although acknowledging the greatness of the film, didn't see the same perfection. "Though some sequences . . . have a documentary-like quality, other . . . have the look of Hollywood art direction and expertise. The occasional glass shots, and the high-powered emotionalism of the parting and ultimate reunion of the two lovers . . . are moving, but possibly a trifle artificial in light of the underplayed treatment such sequences were given in films about World War II. Nevertheless, the sincerity and the overall impressions of 'The Big Parade' linger. . . . 'The Big Parade survives as the first really important film about World War I." (13)

The Warner Blu-Ray release has also been universally praised - as well it should! This is a Kevin Brownlow production with a Carl Davis score which immediately lets silent film fans know it's of the highest quality. The film was restored in 2004 from an original camera negative, and this 1080p/AVC MPEG-4 rendering provides superb quality - sharp and clear with the contrast one would expect from a film made today. Not enough can be said of Carl Davis' score which adds immeasurably to the enchantment of this film. In the film's liner notes, Brownlow acknowledges that Davis "did not find much inspiration" in the original score that was composed by David Mendoza and William Axt but drew appropriately from period themes such as "Over There," "You're in the Army Now," "Mademoiselle from Armentieres," and "My Buddy." Davis is quoted as saying, "A silent film is harder work for the composer than it is on a sound film where a whole battery of special effects is available. On a silent film, the score has to do everything" - and that it does . . . most effectively! (14) Performed by a 45-piece English chamber orchestra, the DTS-HD Master Audio 5.1 provides clear, crisp sound for maximum enjoyment.

References

1. Vidor, King. A Tree is a Tree. Harcourt, Brace and

Company. New York. 1952.

2. Ibid.

3. Ibid.

4. Ibid.

5. Brownlow, Kevin and John Kobal. Hollywood, The Pioneers. Alfred

A. Knopf, New York. 1979.

6. Ibid.

7. Kobel, Peter, The Library of Congress. Silent Movies: The Birth

of Film and the Triumph of Movie Culture. Little, Brown and Company.

New York. 2007.

8. Brownlow.

9. Luft, Herbert G. "King Vidor." Films in Review. December

1982.

10. Brownlow, Kevin. Warner Brothers Blu-Ray DVD liner notes.

2013.

11. Sandburg, Carl. "The Big Parade" review. Chicago

Daily News, December 29, 1925.

12. Sherwood, Robert. "The Big Parade" review. Life

Magazine. December 1925.

13. Everson, William K. American Silent Film. Oxford University

Press. New York. 1978.

14. Davis, Carl. Quoted in the Warner Brothers Blu-Ray DVD release

liner notes.

Copyright 2013 by Tim Lussier. All rights reserved.