During the course of compiling information for our Conrad Veidt on Screen, my research colleague, Michaela Krause, was poring over microfiche files in German film archives when she was asked by one of the staff members just why she was going to the trouble of writing about Conrad Veidt when there were so many "worthier" subjects to be found in the history of Teutonic cinema. Michaela was taken aback, as was I, when I was informed of this comment some time later. So, I suspect, would be Conrad Veidt's many fans. One cannot deny that there are still plenty of film folk whose efforts have not yet been recognized and whose biographies have not yet been written, but as the lion's share of coverage afforded to "silent stars" has traditionally been forthcoming from "fans," it remains for the fans of those "worthier" folk to pick up the gauntlet.

Folks like us -- the fans -- who

are more than casually interested in the silent era, the "classic"

cinema, and the vast area of overlap, have found in websites such

as this one the perfect complement to the specialized publishing

houses and collectors' newspapers and magazines that have provided

fuel to our fires over the years. We've been individually and

collectively appreciative for individuals like Enno Patalas, David

Shepherd, and Kevin Brownlow, who have been rediscovering and

restoring hitherto lost or fragmented silents for decades. We've

been enormously grateful to the sundry private and government-sponsored

film archives throughout the world for  conserving

these films in the first place, and for underwriting many of these

restorations subsequently. We still owe a tremendous debt of gratitude

to private collectors, who -- in any number of instances -- have

kept lost films from becoming truly extinct, as well as to "gray

market" video dealers, who have made many of these available

to the common clay. We get down on our knees and thank God for

KINO and a handful of other companies whose profit margins are

small, but whose corporate philosophies are cosmic. And we can

only marvel at the prolific output of cinema historians like Anthony

Slide.

conserving

these films in the first place, and for underwriting many of these

restorations subsequently. We still owe a tremendous debt of gratitude

to private collectors, who -- in any number of instances -- have

kept lost films from becoming truly extinct, as well as to "gray

market" video dealers, who have made many of these available

to the common clay. We get down on our knees and thank God for

KINO and a handful of other companies whose profit margins are

small, but whose corporate philosophies are cosmic. And we can

only marvel at the prolific output of cinema historians like Anthony

Slide.

For all this, however, we continually turn to each other for the factoids, the minutiae, the specs, the opinions, the nitty-gritty, the PLEASURE that's inherent in the love of silent cinema. The pros have given us the basic tools, have shared the inside information, have even participated in the online chatrooms and the web-hosted discussions. But we fans have ever been filling in the blanks. And we have mega-fans Vivienne Phillips, Pat Wilks Battle, Werner Mohr, Olaf Brill, Henry Nicolella, and Michaela Krause to thank for filling in this one.

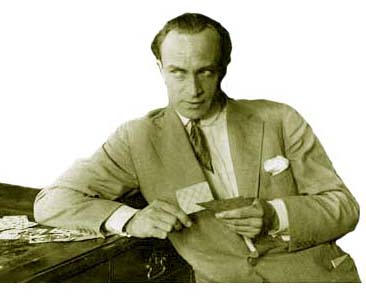

Hans Walter Conrad Veidt was born in Berlin on January 22, 1893, and died on the Pacific Palisades on April 3, 1943. His birth was anticipated; his death was sudden and untimely. What lay between the stone-etched dates was a career that earned him renown as an artist and a philosophy that made him a hell of a human being.

"Connie" first sauntered onto a stage when he was in high school and began to haunt stage-doors -- clad ostentatiously in slouch hat, cape, and monocle - not long thereafter. Luck and serendipity resulted in an audition for theatrical genius, Max Reinhardt, and something Reinhardt saw in the skinny youth resulted in a year-long contract as an extra at the prestigious Deutsches Theater. Service in the Great War interrupted Connie's minor theatrical duties, but his being furloughed due to illness brought him back to the Deutsches Theater, albeit in speaking roles, late in 1916. A future onstage seemed to be a foregone conclusion, when purveyors of the bastard art -- film -- started sniffing 'round. Connie regarded movies as "low, low entertainment," but the amounts of money being offered helped to elevate his opinion, and he embarked on his lengthy film career the following year.

The handsome young thesp started out playing (to use Pat Wilks Battle's phrase) "turban roles," as his first efforts included Robert Wiene's "Furcht" (the earliest extant Veidt film) and Paul Leni's "Der Rätsel von Bangalor." The exotic headgear would later reappear sporadically on the Veidt-kopf, most notably in Joe May's epic "Das indische Grabmal" (1921) and Alexander Korda's no less ambitious "The Thief of Bagdad," in 1940. These latter productions would monopolize Connie's time for months, of course, but the 1917 productions kept him busy only until the light faded. At night, Connie could usually be found onstage at the Deutsches Theater.

It was at the theater that Richard Oswald first noticed the cadaverous actor, and Connie was soon hired to appear in a number of Oswaldfilme. No turbans this time around, though. At this point in the proceedings, Oswald was keeping very busy cranking out "Aufklärungfilme," or "enlightenment" films: pictures that ostensibly warned the unwary of the sexual dangers lurking behind every door, but which were, in most instances, merely exercises in exploitation and soft-core pornography. Arguably the most memorable of these enlightenment films was "Anders als die Andern" which dealt, not with the ravages of venereal disease, but with homosexuality. To quote Veidt biographer, Pat Wilks Battle, "The picture created a box-office sensation, bringing Oswald a great deal of money and Veidt an avalanche of fan mail. It failed, however, to bring about a revision of paragraph 175 (of the German penal code, which outlawed certain homosexual acts between consenting adults]."

Connie was soon directing himself in motion pictures, having money enough to start up his own production company. Veidtfilme would fold after "Wahnsinn" (1919) and "Die Nacht auf Goldenhall" (1919/20), but the actor was soon engaged in a series of pictures under F.W. Murnau, with whom Connie had apprenticed at the Deutsches Theater. Apart from "Der Gang in die Nacht," however, every one of the five films the men made together remains lost. Still, Murnau's "Satanas" (1919), along with Oswald's "Unheimliche Geschichten" (also 1919) and Veidt'd own "Wahnsinn," contributed in proffering the ticket-buying public its first views of the "Demonic Veidt," a representation of the myriad aspects of Man's darker self. The Demonic Veidt would soon reach its apotheosis in Robert Wiene's Expressionist masterpiece, "Das Cabinet des Dr. Caligari" (1919).

"Caligari" introduced America to Conrad Veidt and brought the actor the fruits of international fame. It also assured plenty of opportunities for the cameras to favor that demonic side; peppered among the more mundane dramas that followed were "Patience: Die Karten des Todes" (Patience: Death's Calling Cards), "Kurfürstendamm," and Murnau's unauthorized Jekyll & Hyde treatment, "Der Januskopf." The change of decades saw the intimacy of "Kammerspiel" give way to historical epics, grounded in history and accoutered in brocade and with magnificence. Oswald's "Lady Hamilton" (1921) and "Lucrezia Borgia" (1922) bracketed the sumptuous nonsense of the two-part "Das indische Grabmal," which had been scripted by Fritz Lang (from his wife, Thea von Harbou's, original story) and appropriated by Joe May. Connie's inimitable presence here -- and in Oswald's later "Carlos und Elisabeth" -- added to the films' popularity and success.

Paul Leni's brilliant episodenfilm, "Das Wachsfigurenkabinett" (1924), made American audiences sit up and take notice of the lean and riveting Veidt. The picture, along with Wiene's "Orlacs Hände" (1924) and Henrik Galeen's remake of "Der Student von Prag" (1926) reinforced the image of the Demonic Veidt, but it was the English-language print of "Waxworks" that convinced John Barrymore to invite Connie to Hollywood in 1927. Barrymore was set to film "The Beloved Rogue" and the Great Profile had determined that only Veidt could bring to the role of Louis XI the qualities that history (and the screenplay) had endowed upon the eccentric king. "The Beloved Rogue" was a hit and -- although the German trade press grumbled over the perceived inadequacies of Tinseltown -- Conrad Veidt stayed on in America until the dawn of talkies.

"Uncle" Carl Laemmle's Germanic roots doubtless played a part in his success in signing Veidt to a multi-picture contract with Universal, and Connie's last purely silent films -- "A Man's Past" (the actor's only lost American picture) and "The Man Who Laughs" (for his old friend, Paul Leni) -- and the silent version of the aborted part-talkie, "The Last Performance," were all Universal productions. ""The Man Who Laughs" was recalled after its initial release, so that a synchronized music and effects track could be added. A last reel concession to dialogue in "The Last Performance" proved to be untenable when the film was screened in previews, and the Paul Fejos effort was subsequently viewed (and reviewed) as a totally silent movie.

Conrad Veidt's career continued through the awkward "cusp of sound" days, of course, and the actor went on to make more than three dozen sound films in a variety of languages. It is ironic to note that the man who had fled Nazi tyranny, arm in arm with his Jewish wife, ended up being Hollywood's quintessential Nazi. Having become a British citizen in 1939, he turned over his entire personal fortune to the British government, interest-free. Having won his initial fame in silent pictures, he allowed his German-cadenced English to be heard in anti-Nazi radio broadcasts and sound films. When he died of a massive heart attack, he was laid to rest without an epitaph. It remained for his old friend, producer Eric Pommer, to reflect, "It is hard to say what was more to be admired in him, his artistry or his humanity."

That, as the saying goes, is another story.

copyright 2003 by John T. Soister. All rights reserved.

Read the "Silents Are Golden" review of "Conrad Veidt on Screen"