Jesse L. Lasky Feature Play Company

Paramount Pictures

Cast: Fannie Ward (Edith Hardy), Jack Dean (Richard Hardy), Sessue Hayakawa (Haka Arakau), James Neill (Jones), Utako Abe (Arakau's valet), Dana Ong (District Attorney)

Although New York stockbroker Richard Hardy

is experiencing financial difficulties until a new investment

pays off for  him, his wife Edith continues her

spendthrift ways. Haka Arakau is a Burmese ivory king who is popular

with Edith's social set. Although her husband doesn't approve,

Arakau spends a great deal of time in Edith's company. As treasurer

of the local Red Cross, she is entrusted with $10,000 in funds

they have raised.

him, his wife Edith continues her

spendthrift ways. Haka Arakau is a Burmese ivory king who is popular

with Edith's social set. Although her husband doesn't approve,

Arakau spends a great deal of time in Edith's company. As treasurer

of the local Red Cross, she is entrusted with $10,000 in funds

they have raised.

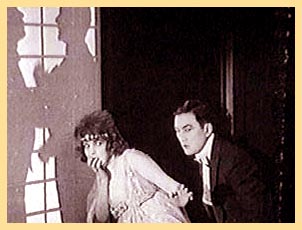

One evening at the Hardys' home, Jones, a friend of Richard's, tells Edith her husband is making an unwise investment and should have invested his money in United Copper stock. Since her husband has cut off her spending, Edith has an idea and gives the man the $10,000 from the Red Cross fund to invest in this stock, explaining that she won the money playing bridge. However, the investment fails, and Edith fears a great scandal. Arakau offers to give her the $10,000 in return for sexual favors. She agrees.

In the meantime, Richard's investment makes them rich. Edith is due to pay her end of the bargain to Arakau that evening. Instead, she gets $10,000 from her husband, on the pretense of paying bridge debts, and goes to repay Arakau. He refuses to accept the money and attempts to rape her. She resists, and he "brands" her on her shoulder with a red-hot iron he uses to mark his possessions. She shoots him and runs away. Richard, being suspicious of his wife, discovers the wounded Arakau, is caught with the gun in his hand and arrested.

In his tribute to silent film, Seductive

Cinema (Alfred A. Knopf, 1994), James Card, founder of the

George Eastman film archive, devoted over three pages solely to

"The Cheat" heaping praise on the film. According to

Card, he approached Cecil B. DeMille's daughter,

Cecelia, about donating the DeMille collection to Eastman House

in 1959, shortly after the director's death. Of the more than

3,000 35mm nitrate positives he obtained were titles such as "Carmen,"

"Joan the Woman," "A Romance of the Redwoods,"

"The Little American," "Don't Change Your Husband,"

"Male and Female," "The Affairs of Anatol,"

and more. However, of these films, Card said, "But the biggest

surprise to me was 'The Cheat' -- a towering masterpiece of 1915."

Card said he felt an "evangelistic compulsion" to show

the film to "skeptical audiences" and began a series

of screenings both in the United States and Europe over the next

several years.

B. DeMille's daughter,

Cecelia, about donating the DeMille collection to Eastman House

in 1959, shortly after the director's death. Of the more than

3,000 35mm nitrate positives he obtained were titles such as "Carmen,"

"Joan the Woman," "A Romance of the Redwoods,"

"The Little American," "Don't Change Your Husband,"

"Male and Female," "The Affairs of Anatol,"

and more. However, of these films, Card said, "But the biggest

surprise to me was 'The Cheat' -- a towering masterpiece of 1915."

Card said he felt an "evangelistic compulsion" to show

the film to "skeptical audiences" and began a series

of screenings both in the United States and Europe over the next

several years.

Card's enthusiasm is not without justification. "The Cheat" is an amazing film in many respects, especially considering it was made in 1915, an early point in screen development. Although "The Birth of a Nation," also made in 1915, is obviously of much greater scope, "The Cheat" is a more highly polished film, almost betraying the time in which it was made. Card expounded, "The low-key, atmospheric lighting is sophisticated and effective far ahead of its time. The Japanese screens used to silhouette players, who are ripped apart in violence behind them, the screens suddenly spattered with blood, make the film look as though it could have been made by Kurosawa rather than the unappreciated DeMille."

Card is not the only one who has high praise for the film. Its is revered almost universally. Kevin Brownlow, in The Parade's Gone By (Bonanza Books, 1968) said, "Tautly constructed and excellently played . . . The branding sequence, and the subsequent shooting, are lit in a way that ignites the imagination; the scenes are as powerful as ever today."

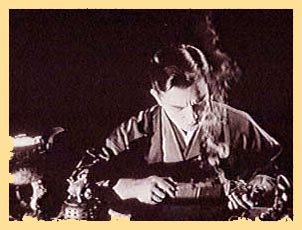

The look of the film certainly deserves

comment for it adds greatly to the imposing, somber atmosphere

of the story. Our introduction to Arakau shows him seated at a

table with a small, very hot, branding iron in one hand and one

of his small ivory statues in the other. A metal bowl on small

legs is on the table to his right, glowing brightly from the heat

source within, which is used to heat his branding iron. All is

dark around Arakau save the light from the bowl and a spot directed

on his face. He presses the hot iron to the

statue, and we see smoke rise in the darkness as it sears the

statue. His work completed, Arakau places a lid over the bowl.

The spot is extinguished, and only bands of light from the openings

in the lid streak his face. What a compelling introduction to

this mysterious Oriental man!

on his face. He presses the hot iron to the

statue, and we see smoke rise in the darkness as it sears the

statue. His work completed, Arakau places a lid over the bowl.

The spot is extinguished, and only bands of light from the openings

in the lid streak his face. What a compelling introduction to

this mysterious Oriental man!

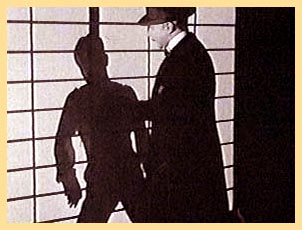

Twice DeMille uses an Oriental screen in Arakau's home to great effect. In a semi-dark room, Arakau comforts Edith after learning she has lost the $10,000. On the other side of the screen, we see the shadow of Edith's husband and a friend. The effect heightens the tension as she and Arakau cower in fear of discovery. In an even more compelling scene, Edith has just left Arakau's home after shooting him. Richard arrives at the home and sees the shadow of Arakau slumping against the screen. Suddenly, because of his weakened condition, Arakau slides down to the floor leaving a trail of blood on the screen. Hardly what you would expect to see in 1915 American cinema!

The only criticism aimed at the film has

come about because of an alleged "racist" tone. Brownlow

called it "unashamedly racist." Edward Wagenknecht,

in Fifty Great Silent Films 1912-1920 (Dover, 1980) said,

"The most shocking thing about 'The Cheat' today is its naked

appeal to race prejudice." Since Arakau is included readily

as a part of Edith's elite Long Island social circle, this opinion

seems harsh. However, the courtroom scene at the end may lend

itself more to any racial claims. When Edith reveals her brand

and implicates Arakau as the villain, the people in the packed

courtroom become a mob pressing toward Arakau who is saved by

the judge and quickly removed by a bailiff. However, would the

crowd's reaction have been less believable or effective if Edith's

attacker had been a villain of any other nationality? Variety

thought so when its reviewer said, "Without the third point

of the eternal triangle having been one of an alien race the role

of Edith Hardy in this picture would have been one of the most

unsympathetic that has ever been screened." Still, it is

interesting to ponder the film's effectiveness if the villain

had been a despicable scoundrel of  another

nationality, further making one question just how "unashamedly

racist" "The Cheat" really is.

another

nationality, further making one question just how "unashamedly

racist" "The Cheat" really is.

Apparently the Japanese of California thought it was certainly racist as protests, including one from the Japanese Embassy, brought about a change in the film. In its original 1915 release, Sessue Hayakawa played a Japanese named Tori. Because of the protests, and the fact that Japan was an ally at the time, his character was changed to a Burmese in the 1918 re-release. (This is the version reviewed here. In the original 1915 version, Hayakawa's Japanese character was named Tori.)

Actually, historians and contemporary reviewers alike seem to be in agreement that the film would not have been the same with Hayakawa's presence. The great French writer Collette said, "To the genius of an Oriental actor is added that of a director probably without equal." She goes on to praise Hayakawa's acting with "Let them take to heart the menace and disdain in a motion of his eyebrow and how, in an instant when he is wounded, he creates the impression that his life is running out with his blood, without shuddering, without convulsively grimacing . . ." The New York Times reviewer said, "Miss Ward might learn something to help her fulfill her destiny as a great tragedienne of the screen by observing the man who acted the Japanese villain in her picture." According to Variety," . . . the work of Sessue Hayakawa is so far above the acting of Miss Ward and Jack Dean that he really should be the star in the billing for the film." Card said, "Without the acting of Sessue Hayakawa, the film might go down as wild melodrama."

The acting in the film is certainly one of the surprises of "The Cheat," and, without question, of the three leading players, Hayakawa's performance is the far superior. His acting is restrained, somewhat uncommon for 1915, but, nevertheless, conveying emotions effectively and with intensity. Brownlow quotes Hayakawa discussing the scene in which Edith implores Arakau to drop the charges against her husband. "I was always taught that it was disgraceful to show emotion. Consequently, in that scene, as in all other scenes, I purposely tried to show nothing by my face. But in my heart I thought, 'God how I hate you.' And, of course, it got over to the audience with far greater force than any facial expression could."

The metamorphosis

of Arakau from the first half of the film to the second half is

a credit to Hayakawa's skills. In the first half, he is a smiling,

sociable tag-a-long among Edith's social set. After Edith "cheats"

him, his is a sadistic, revengeful character whose eyes and tautness

of jaw instill a sense of fear and foreboding in the viewer. As

for the branding scene, Ward and, especially, Hayakawa give superb

performances that are exceptional in the silent drama - giving

us a scene that will assuredly electrify any viewer's emotions.

The metamorphosis

of Arakau from the first half of the film to the second half is

a credit to Hayakawa's skills. In the first half, he is a smiling,

sociable tag-a-long among Edith's social set. After Edith "cheats"

him, his is a sadistic, revengeful character whose eyes and tautness

of jaw instill a sense of fear and foreboding in the viewer. As

for the branding scene, Ward and, especially, Hayakawa give superb

performances that are exceptional in the silent drama - giving

us a scene that will assuredly electrify any viewer's emotions.

In his autobiography (Autobiography, Prentice-Hall, Inc., 1959) DeMille debunks the myth that Hayakawa was a poor gardener whom he discovered. "The truth of the matter is at once more prosaic and more plausible," he said. "Sessue, a highly educated gentleman of exquisite taste, had played in a few pictures but was not getting much work when I engaged him for the lead in 'The Cheat.' After that, he had all the work he could handle for several years."

Hayakawa continued successfully in silent films until the early twenties when he left Hollywood and made films in Europe. He was prominent once again in American films in the late 1940's and 1950's when Japanese character parts were plentiful. His most memorable role during this time was in "The Bridge on the River Kwai" (1957). His last appearance on film as in "The Big Wave" (1961). He died in 1973 at the age of 84.

"The Cheat" was Fannie Ward's first film appearance and immediately made her a star. She was 43 years old when she made this film having previously enjoyed a long, successful stage career. Jack Dean, who played her husband, Richard Hardy, was also her real-life husband. Ward went on to have a successful career in films over the next five years, many of them co-starring with Dean. However, after 1921, she decided she preferred vaudeville. The rest of Ward's life was spent between the United States and Europe enjoying her wealth. At one time she opened a Paris beauty shop called "The Fountain of Youth," making reference to her youthful appearance and reveling in the fact that no one could determine her exact age. Dean died in 1950, and Ward followed on January 27, 1952.

The New York Times called "The

Cheat" "sensational trash" and "an old-fashioned

melodrama." This was definitely a minority opinion. Moving

Picture World said, " . . . the feature is of such extraordinary

merit as to call for the highest term of praise." The

New York Dramatic Mirror claimed, "'The Cheat' is a mighty

fine photoplay, well conceived, well written, carefully produced,

and extremely well acted . . ." Variety said, "The

picture as a feature will surely be a box-office winner,  for it carries a lot of punch of 'virtue for

dollars' stuff that is sure to appeal."

for it carries a lot of punch of 'virtue for

dollars' stuff that is sure to appeal."

Gabe Essoe and Raymond Lee in their book DeMille, The Man and His Pictures (Castle Books, 1970) claim DeMille had a difficult time convincing Jesse Lasky that "The Cheat" was worth making. They go on to say, "DeMille's stand on wanting to produce 'The Cheat' was significant in that it showed he had an extrasensory perception that made him aware of an approaching tidal wave of public taste long before anyone else . . ." This may be so, although some may claim "The Cheat" is just an early example of DeMille's predilection for sensationalism and boldness in pushing the censors to the limit. Some of his critics claim he used the Bible in his later pictures as a means to get sex past the censors and on to the screen.

However, it is unfair to label "The Cheat" in this manner. This is quality filmmaking, and it is obvious DeMille was seeking quality in the cinematography, the acting and the story. Although DeMille claims he worked on "The Cheat" from 9 a.m. until 5 p.m. then worked on "The Golden Chance" until 2 or 3 a.m., "The Cheat" is not a quickie programmer that was treated lightly. His insistence that Lasky produce the film is a clear indication of his high regard for it, and the production values show this. "The Cheat" is one film that does not require excuses because it was made in 1915; it is very capable of standing on its own merits -- and it stands head and shoulders above all but a few of its contemporaries. As Card said, "It would be hard to imagine a scenario more unlikely to be offered to the American public in a 1915 movie . . ." but, then again, without vision, a movie can't stand as a classic into the next century as "The Cheat" has.

copyrright 2002 by Tim Lussier, all rights reserved