Susie May Trueheart (Lillian Gish), a country girl, loves her neighbor William Jenkins (Bobby Harron), but in spite of their good fellowship together, William is as blind to her in a romantic aspect as David Copperfield was to Agnes. Unbeknownst to William, Susie sells her cow and other possessions to secure the wherewithal to send him away to college to study for the ministry and thus fulfill his ambition to become a man who amounts to something.

After his graduation, William returns, and Susie has the

satisfaction of hearing him preach his first sermon. But her hopes

are dashed when William is fascinated by a beautiful but frivolous

and worthless girl, Bettina Hopkins (Clarine Seymour).

Susie swallows her pride and grief to serve as bridesmaid at the wedding, but the marriage is a disaster. Totally unqualified as a minister's wife, Bettina takes to cheating with "Sporty" and his dissipated friends. After being caught in a terrible storm, she takes ill because of exposure and dies.

Susie, who knows the truth, protects the dead girl's memory and shields William from the pain of knowing his wife's unworthiness by concealing from him the true nature of his wife's excursion, and William vows never to marry again. This is too much for [Susie's] aunt, who now tells William who paid for his education, and Bettina's friends enlighten him as to the true character of her excursion. His eyes opened at last, William realizes that Susie is his true love. (Quoted from The Films of D. W. Griffith)

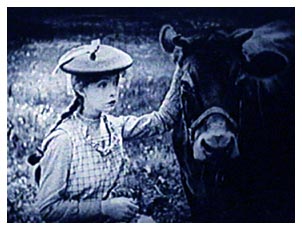

When "Silents Are Golden" websmaster Tim and I were on our way to the 2002 Cinevent, we stopped at the little country hamlet of Crestwood, Kentucky, to visit the grave of D. W. Griffith at Mt. Tabor Methodist Church, where he worshipped as a boy. (See "A Visit to Mt. Tabor: D.W. Griffith's Final Resting Place") Seeing the lovely and simple burial place of the Father of American Film was an ineffably moving experience, and I expressed hope at the time that the pastoral sequences in Griffith's films - "the simple sequences that must have seemed throwaways to earlier generations of filmgoers for whom the pastoral was an understood form of art, for whom a closeness to the land and to family was more often a given than it is today" - would play a major role in ensuring the survival of Griffith's legacy. I added that

There are scores of these [pastoral] miniatures across the canvas of Griffith's work, and doubtless you have your own favorites. And of course there is so much more to Griffith than individual sequences or shots. But one quickly comes to notice how Griffith lingers on these miniatures, rather in the way we might linger over a favorite photograph or keepsake from the past; the image before us suddenly takes on a warmth and humanity as fresh as the day it was caught on film. To put the point another way: in viewing Griffith's work from the early Biographs to the romances and great symphonies of the 1910's and 1920's, one marvels at his skill in marshaling his resources to create (as Orson Welles termed it) the very language of motion pictures. But in these quiet, glowing moments, one senses Griffith's love; and here the medium of film takes on its greatest power -- not to excite, not to hold in suspense, but to speak with directness to the heart. Few directors have understood this power as well as the Kentuckian who discovered it.

When I wrote those words, however, I had yet to see "True

Heart Susie" (1919). Oh, there was the glowing approbation

of the notoriously severe Pauline Kael from the 1960's: "A

lovely, simple pastoral romance - one of the most charming of

all D. W. Griffith's films. Close to perfection, on a small scale."

And Richard Schickel, writing in his D.W. Griffith: An American

Life in 1984, had equally deep affection and admiration for

the film. Noting that it was released only two weeks after "Broken

Blossoms," one of Griffith's most  legendary

works, Schickel lamented that this "charming" work was

critically neglected at the time of its release:

legendary

works, Schickel lamented that this "charming" work was

critically neglected at the time of its release:

It is the last film in which Griffith draws directly upon his warmest memories of a bucolic childhood, and the last of his looks backward at a fast-vanishing America without the intervention of subplots, chases, sexually imperiled heroines, and the rest of his beloved melodramatic contrivances. It also includes a performance by Lillian Gish that is among her finest [and] more overtly comic, at times gently parodying those conventions of girlish innocence also beloved by Griffith. She gives a certain tartness to a role that is always dangerously close to excessive sweetness.

Enticing words, those, but even they were trumped by Professor Tom Gunning's notes for a 2006 screening at the Pordenone Silent Film Festival: "There are those of us who consider "True Heart Susie" to be Griffith's masterpiece . . . . [one] nearly incandescent in its confessional and emotional power." All of which left Griffith fans everywhere wondering why this undoubted masterpiece was available only in dupey public-domain prints.

Small wonder, then, that when word came earlier this year that sainted film preservationist David Shepard would be releasing a DVD of the British Film Institute's 35mm duplicate negative with accompaniment by Rodney Sauer's Mont Alto Motion Picture Orchestra, the glory hallelujahs rang long and loud, joined on August 28 (the DVD release date) by none other than the New York Times. Calling "Susie" "one of [Griffith's] most beautiful films," the NYT's reviewer added that

As one of the handful of filmmakers for whom the rural

United States of the 19th century was a living memory, Griffith

paints a convincing portrait of a bygone land. And as American

film shifts into a digital realm, his work seems more and more

essential: his use of landscapes seen in long shots, the way he

places actors in the context of a natural environment that extends

into infinity, is just as important (if not more so) than his

celebrated use of the close-up.

"True Heart Susie" may be close to 100, but you can

still feel the warmth of the day, hear the rustling of the wind

and see the clouds scudding across the sky, conveyed with a sense

of wholeness and substance that no digital environment can ever

hope to match.

So here it is, courtesy of Shepard's Film Preservation Associates and released through Image Entertainment, and it's beautiful. As for the response it invites -- think of one of Rhett Butler's lines in "Gone With the Wind": "Dare I name it? Can it be love?"

Indeed it's love; most assuredly it is love. Caveat emptor, however, for there are the usual Griffith idiosyncrasies to contend with: There are fade-ins and fade-outs within a scene; the continuity from medium shot to close up often is so far off that we see a basic action or response occur twice; intertitles are sometimes preachy, and -- shades of the Biograph days -- they often announce what is about to happen and thus slacken the narrative tension.

All right, then: let's at once accept those quirks and let

them go. Here we have Griffith at his happiest, rather as he might

have been during the halcyon days at Biograph,  presiding

over a simple story peopled with his favorite players, setting

his few characters against lovely backgrounds that take the breath

away, emphasizing the small touches of character that give his

films life, keeping all in one congruent whole.

presiding

over a simple story peopled with his favorite players, setting

his few characters against lovely backgrounds that take the breath

away, emphasizing the small touches of character that give his

films life, keeping all in one congruent whole.

There's a touch - more than that, really- of the unexpected, however. How often have we encountered a sly Griffith before? It's one thing to have Lillian Gish and Bobby Harron walking along the countryside as teenage sweethearts might, with Gish making moo-cow eyes at Harron as she leans in expectantly for the kiss that never comes. All's innocence, all's face value. Then comes this title: "Of course they don't know what poor simple idiots they are - and we, who have never been so foolish, can hardly hope to understand - but -" One raises the eyebrows: Griffith with knowing irony? This is nice, leavening as it does what otherwise might be a slightly stale storyline, however delicious its fragrance of apple blossoms. But there's more: when Harron and Gish are enjoying ice cream in a drugstore, Harron points to two floozies: "You see those two, painted and powdered? Men flirt with that kind, but they marry the plain and simple ones." And as Gish primps with satisfaction, we are told that "Susie, dimly conscious that she is both plain and simple, takes this entirely too seriously." Come again? Simple Susie, who bested William in a spelling bee and looks with sly amusement at his twirling his collegiate moustache? Simple Susie, who says "I must marry a smart man"? Plain Susie, of shining eyes and pre-Raphaelite beauty, on whom Billy Bitzer lavishes some of the loveliest close-ups of Lillian Gish's long career? Neither the director nor Susie herself underestimates her attributes, which estimation of course leaves William's blindness all the more eye-rolling for both the viewer and probably for the director as well: when Seymour's Bettina throws herself at Harron's credulous William, Griffith informs us that "William's great simple heart cannot believe that all are not like himself."

That Gish is able to make such repressed yearning and intelligence believable, aided by Harron's naiveté gradually segueing into wisdom, speaks for the film's strongest attribute, aside from its photography: its acting. Part of the problem with Griffith's films now is that amidst a well-acted ensemble, one or several performances will strike a jarring, wildly flailing note: Donald Crisp is too brutish in "Broken Blossoms," Josephine Crowell scowls like King Kong through the Huguenot episode of "Intolerance," the hayseed comic players in "Way Down East" are simply dreadful, and we'll draw a curtain of charity over the blackface players in a number of Griffith films. But "True Heart Susie" stands with "Isn't Life Wonderful" as the Griffith work with the best ensemble acting. Harron's sensitive, expressive face makes his transformation from a gullible country boy, to a cocksure seminary graduate, to a humbled and contrite man, most absorbing; if we never quite believe that William could be so oblivious to Susie's charms, it's the fault of the screenwriter (Guess who?), not Harron. Clarine Seymour's Bettina, all flashing eyes and hungry-for-life mouth, is by turns pitiable and contemptible, not to mention surprisingly contemporary. (How sad to reflect that both of these talented actors, so young and fresh, would be dead within a year of the film's release.)

Gish, however, is a revelation.

Her shy, stringently controlled Susie can express joy and abandonment

only within the confines of her home (and sharp-eyed viewers will

be moved when she speaks happily to a picture of her dead mother:

it's the same photograph of Mary Gish and baby Lillian that Gish

would address some sixty-eight years later in her final film,

"The Whales of August"). But her passive silence around

William (waiting expectantly for his approval, even his recognition,

as it were) is laced with a keen-eyed and shrewd awareness of

William's limitations of both intellect and vision. When she gently

steers him away from a nubile admirer, subtley nods him in the

direction of the ice cream parlor, and coolly (so coolly that

you have to watch for it) endures his arm-waving sermon rehearsals,

we know who's pulling the strings with a delayed payoff in mind.

Gish's finest scene, then, may come when William asks Susie if

she thinks he should be married: her eyes eagerly searching his

face, she barely conceals her joy before she demurely examines

her ring finger. Here, and even more so in the extended close-up

of her discernment that William's heart actually is drawn to Bettina,

Gish's expectancy, vulnerability, and hurt are devastating; I

think these shots surpass in poignancy even the famous close-up

within the closet sequence of "Broken Blossoms," if

only because they are so tender and quiet.

Gish, however, is a revelation.

Her shy, stringently controlled Susie can express joy and abandonment

only within the confines of her home (and sharp-eyed viewers will

be moved when she speaks happily to a picture of her dead mother:

it's the same photograph of Mary Gish and baby Lillian that Gish

would address some sixty-eight years later in her final film,

"The Whales of August"). But her passive silence around

William (waiting expectantly for his approval, even his recognition,

as it were) is laced with a keen-eyed and shrewd awareness of

William's limitations of both intellect and vision. When she gently

steers him away from a nubile admirer, subtley nods him in the

direction of the ice cream parlor, and coolly (so coolly that

you have to watch for it) endures his arm-waving sermon rehearsals,

we know who's pulling the strings with a delayed payoff in mind.

Gish's finest scene, then, may come when William asks Susie if

she thinks he should be married: her eyes eagerly searching his

face, she barely conceals her joy before she demurely examines

her ring finger. Here, and even more so in the extended close-up

of her discernment that William's heart actually is drawn to Bettina,

Gish's expectancy, vulnerability, and hurt are devastating; I

think these shots surpass in poignancy even the famous close-up

within the closet sequence of "Broken Blossoms," if

only because they are so tender and quiet.

There's a story - perhaps apocryphal, but probably not - that when Bette Davis, Gish's "Whales of August" co-star, was told during shooting that Gish had performed wonderfully in a close-up that day, she replied, "She should. She invented them." While Gish may not have invented the close-up, she and Griffith brought to it a power to explore the human soul that nearly a century's passing cannot begin to touch. Here in these close-ups, together with the pastoral backdrop that Griffith knew and loved, one finds the purity and beauty that have moved viewers and critics alike since "True Heart Susue" was first released. Add to this mixture a lovely print and wistful score compiled by Rodney Sauer and played by the Mont Alto Motion Picture Orchestra, and Kael's words - "[L]ovely, simple, pastoral. [C]lose to perfection on a small scale" - are beyond reproach. It's not a film for the hip or the cynical. Or maybe it is, for it attests to the truth of what the New York Times recently noted about the DVD release of G. W. Pabst's "The 3 Penny Opera," another film from olden days: "Here again is proof of what a fragile medium the movies are, and of how foolish it is for us to condescend to the perceived primitivism of a past that is largely a creation of our own neglect." Amen to that.

Copyright 2007 by Dean Thompson. All rights reserved.